William Gamul Farmer’s career

Nine writers were appointed to the Bombay residency in 1763 according to EIC records.[1] Of five there is no trace later than 1768. One more survived until his return to England in 1780. Two appear in the records till the 1790s. William’s death in January 1798, at 51, made him long-lived by these standards, though not by those of his long-lived family – Sam survived till the age of 93. India was a notoriously unhealthy place for Europeans at that time.[2] In part, this high mortality rate was due to tropical diseases, malaria in particular: one of William’s requests to his brother is for ‘bark’ otherwise quinine, then the only remedy (December 1789). But it was also in part because of their failure to adapt their habits to the climate. According to one contemporary observer, ‘many newcomers shorten their days by a mode of life unsuitable to the climate, eating great quantities of beef and pork and drinking copiously of the strong wines of Portugal in the hottest season. In addition they persisted in wearing European dress which restricted the free circulation of the blood and made the heat more intolerable by confining the limbs.’[3]

William’s petition for an EIC writership was standard; it included proof of baptism, of having been educated in writing and accounts, (‘a regular course of accountancy after the Garton method’) and also the standard promise ‘to behave himself with the utmost Diligence and Fidelity and is ready to give such Security as your Honours shall require.’[4] The man who recommended him was an Edward Ward, presumably an EIC proprietor, though he is not one of the Company names mentioned in William’s first letter from Bombay in October 1763.

William sounds hopeful of commercial success at first, although he does complain that ‘Bombay is not a place for Writers just come out, everything of necessaries is very dear. Our allowance of 30 rupees a month [£3.10] really not enough for subsistence. There never was anyone ever so parsimonious that could make it serve.’ He has not much help from his superiors. ‘Upon my first landing I was introduced to the governour and delivered my letters. He took no notice of them nor as much as mentioned them to me such is the effect of letters of recommendation. The Governour indeed is a very particular man, he has been a Drudge to the Services all his lifetime.’ But he had better welcome from Mr Spencer, an old India hand and a close ally of Lawrence Sulivan, later chairman of the East India Company in London. ‘Mr Burgess’ letter to Mr Spencer I hardly know what to say about. Mr Spencer sent for me and told me I had been very strongly recommended by Mr Burgess, he made no promise of serving me he very seldom does but if he sees a person sober and steady at business that has been recommended to him he always takes notice of that. I had an invitation to dinner, a thing not a very common.’

William, of course, like all company servants at that date, was allowed to conduct his own, private, trade whenever he was not put to company business. (Company business, meant, at the beginning of his career, endlessly copying EIC correspondence within India and to and from London; his title ‘writer’ meant exactly what it said.) As he points out in this first letter, the Company paid its servants far too little to live on. They had to make money for themselves – or go bankrupt as some in Bombay did, while others returned home without fortunes.[5] This system continued in Bombay till the early nineteenth century; it was the source of the fortunes that were made then – and that had been made in Bengal for many years if among the few rather than the many. It was also the source of the corruption so derided in England in popular description of nabobs, and the reason for the eventual prohibition on private trade first in the Bengal and Madras presidencies and subsequently in the Bombay presidency following the suspect fortunes made, like William’s, down on the Malabar coast. William himself in the letter book complains that the profits and efficiency of the Company were much undermined by servant’s private trade, and is also highly critical of a system which sent many of them to take up office in places where they did not speak the language and had very little idea of local cultural and legal norms—something the Company began to amend itself at the end of the eighteenth century. Understanding language, law and culture was something that William, on the other hand, unusually, appears to have sought out for himself, which may partly have explained his friendships with Malet and Palmer, both much closer to Indian life than the norm.

Company servants were not, of course, allowed to compete with Company trade – much less profitable in Bombay than in Bengal. Nor could they trade directly with England, but had to send goods east, to China, for example. In particular they were not allowed to compete with Bombay in its chief trade in raw cotton and later pepper.

However ‘sober and steady at business’ William might have tried to be he had little luck in early years; pickings in Bombay were few, unlike in Bengal. Fortunately his investments were not always so ill advised as the loan the sixteen-year-old mentions making to the impecunious Mr Waters, without serious attempt to discover if Mr Waters would ever be in a position to repay him. But the loan, in ‘respondentia,’ – that is lending money to other merchants to buy ships’ cargoes – was one way of making money he continued to use through his career in India, successfully enough, judging by the sums his letters claim that he hopes to bring home. Pamela Nightingale, for example, refers to his lending by responentia in 1789.[6]

Despite his managing to stay alive unlike so many of his fellows, William was not without health problems– in particular chronic malaria to judge from his descriptions of the symptoms that forced him to give up his Chiefship at Surat at very short notice in late 1795 and that probably led to his death in England barely two years later. By 1768 he was already having problems of other kind; he requests and is granted the right to return to England for a while for the sake of his health. (In 1769 he is given permission to return to his post). In 1772 he is appointed Assistant to the Marine Storekeeper, one of the posts available to still junior company servants and presumably a good source of information on matters of ships’ cargoes etc. But in the second letter to his father, of 1774, written in the affectionate tone that the father evokes in both sons, while indicating that he is surviving financially he also complains how much harder it has become to make money because of the political situation. ‘When I was in India before I could have lent taking the tune of £10,000 a year safely on respondentia … now it is difficult to lend one rupee safely insomuch that I think it best to let my money lay at the common interest of 9% which I can lay by and keep corresponding yearly…. and with that economy live on the Company allowance… which everything included is only £126 a year and this is little enough let me tell for one who has been in their service now going on 11 years- if had not got the Bakehouse to employment I do not know what I should have done.’ (The Bakehouse was a factory making hard tack, the staple seaman’s diet: William’s attachment to the Marine Storekeeper must have been useful here too. Setting up the bakery appears to have been a piece of typical private initiative on his behalf: throughout his career, the ever-increasing sums he claims he will be able to bring home do suggest that he succeeded in making more money in Bombay than many of his contemporaries, even if not quite the legitimate fortune he was hoping for.) He adds: ‘the greatest profit…. is supplying the Company’s fighting vessels here with Biscuit I do not know what I should have done – in the last year here between you and me I made one thousand pounds of it but do not expect to make this year more than 500 and shall be content with that for among other reductions the Company have lessened their Marine Force here almost a half, the consequence of which you know must be that there will be fewer biscuits cracked.’ (This was due to the dire financial straits of the Bombay Presidency, always a much less profitable station than Bengal and Madras.)

William goes on to claim that with all his other financial strategies he should be able to return to England within four years with £8000, not yet the great fortune that his father might have hoped for but one he could live on. ‘The more I think of it the more I approve of my Plan especially when I consider there is no one depends upon me at present for provision nor I believe ever will be, for unless a man is governed by an unknown destiny in the act of marriage I think I shall die a bachelor.’ This last statement negates both his mother’s and his brother’s attempts to interest him in this ‘flirt’ or that; that the letter is more or less contemporaneous with his affection for William Palmer’s girls might explain in part his lack of interest.

But nor did William leave India: he did not return to England for good until just before his death, despite the period of three or four years he spent there in the 1780s. The letter (17 June 1795) to Palmer states that he had only returned to India because he had invested his money in what he called ‘manufactory’ and lost it all. On the other hand he had not resigned his post meanwhile, which might suggest an ambivalence about his absence. As for marriage – whether his warring parents put him off it altogether, or he did not see himself as making enough to support an English wife, an expensive business in Bombay, and/or he would have preferred to set himself up with an Indian bibi or two like Malet or Palmer or his own first governor, Crommlin – it is impossible to know. He left no will in Bombay providing for any dependents, but this does not mean he had none, any more than the lack of records in the IOR series of any unofficial marriage or of any births or christenings resulting from such a union prove that he remained permanently unattached. Leaving Malet and Palmer aside, he would have had the opportunity, both in Bombay and elsewhere to consort with nautch (dancing) girls; in Bombay, parties to which the local Parsi traders invited customers such as William often included nautch girls dancing. Down in Madras, after parties at the palaces of local Indian nawabs, unmarried Englishmen were reported to go home with the dancers. That said, the Farmers being a conventionally respectable family – the horror evoked by the behaviour of Sam and William’s half-sister is significant – it was more than likely he would have kept such attachments to himself. He lived, moreover, in a society of bachelors: very few wives came out to India before the nineteenth century, and even some of the official ones were Anglo-Indian.[7] Many other bachelors did not marry until they returned to England for good.

The EIC records and, tangentially, the family letters, record that in 1774 William was given permission to go to Madras on private business and that from there was sent to Calcutta as assistant to a John Taylor, a more senior Bombay Servant charged with explaining a recent treaty to the government there. In November 1776 Taylor died. Farmer was again in Madras on business – his Bombay masters complained of his long absence there, and Sam complained of not knowing where his brother was: their mother referred to letters coming from ‘Calcutter.’ (15 and 20 December 1795). Back in England meantime William had been made heir over his mother’s head to her family’s run-down estate in Cheshire. Despite her chagrin, her letters of this date, attempting to entice him home, were all about the orchard she had had planted for him, and about other attempts she was making to bring the neglected estate up to scratch. All this was interwoven with the description of a burglary at her house, probably instigated by a maidservant –‘I got one that let a gang into my house at a celler window and robbed me of more than 30 in cloaths and other things. I heard ‘em in the house but would not ring for fear that I should in coming to me be murdered’, and by descriptions of her attempts to find a doctor to cure her of unspecified ailments (15 December 1795).[8] Later she finds lodgings in London for the winter, only to be forced to move because of the noisy young man downstairs (3 March 1777).

Money continued to be a problem throughout this period, as did William’s health. In 1777 he was one of the signatories to a letter from all the Company servants to the Council complaining about the inadequacies of the company salaries.[9] Shortly after, he was permitted to go to Poonah ‘for his health’ by which chance he was in a position at a time of political crisis to give important intelligence of the Designs of a Monsieur St Lubin, who was endeavouring to conclude an Alliance with the Marathas. (The Marathas were the warlike Indian rulers throughout the territory of the Bombay Presidency, whom the Bombay directorate attempted unsuccessfully during two wars in the 1770s to drive back, while working, more successfully, to keep out the French.) In 1778 William, still in Poonah and with the Maratha problem increasing, was appointed Secretary to the Poonah Committee; two months later he was appointed, too, Marathi translator. There was no indication whether he had learned Marathi while in Poona or whether he had acquired the language in Bombay. The language used among themselves by his Parsi colleagues was Persian, a language William may have acquired, as he did others – certainly, according to a letter to Sam in 1789, he encouraged a protégé to learn it. In the diary of his travels sent to the Bombay Council in December 1793 when he was supervisor of the Malabar province, he complains of having to translate some of his dealings into Portuguese, and appears to indicate some knowledge of the local language besides.[10]

William Gamul Farmer’s knowledge of Marathi was probably one reason he was, along with a Lieutenant Stuart, left as hostage in the camp of the general, Scindia after his defeat of the Company forces in January 1779. The two remained there until March of the following year. No word of this experience to or from William’s family survives, though there is a request from Sam Farmer noted in the EIC court records, 27 April 1780, asking for steps to be taken for the release of his brother.[11] Of the (relatively) contemporary references to it, that appeared in English publications one reports William asking if he and Stuart – both young men still – could swim in a river there: they were refused permission on the grounds that the river probably flowed to the sea and that the Englishmen as water people ‘might escape that way’.[12] The other reference, this time by James Forbes, has William, his ‘intimate acquaintance contriving to send me secretly a few words concealed within the tube of a very small quill, run into the messenger’s ear, to inform me of the enemy’s determination to recapture Dhuboy; advising me […..] to make the best terms possible and deliver up the keys to the Maratha sirdar as all resistance would be vain.’[13]

This was not an easy year for William. To summarise a large amount of correspondence in the EIC records, William was continually asking for money for his various expenses in Scindia’s camp, was in constant danger because of the Company’s immediate failure to keep the terms of the treaty, and because of his supply of secret information to General Goddard commander of the Company army. He was also forced to bribe some of Scindia’s men to prevent them roughing him up and in the end had to pay his own ransom, recouping it from the Bombay Presidency with much difficulty and only with the aid of Warren Hastings himself.[14] It was not surprising that later in his career he so resented his treatment by the Company and expressed his sense that it owed him something for his pains.

Certainly William’s long and sometimes dangerous sojourn in the Poonah area would have deepened his knowledge of an India, that he appears, socially, geographically and linguistically too to have known as well or better than most. John Rennell, the geographer, thanked him for providing information that improved the accuracy of his mapping of the area around Poonah.[15] The close friendship with Charles Malet long-time resident at Poonah there almost certainly stemmed from this time.

Allowed by the Company to go to England after his ordeal, as reported to William Palmer (17 June 1795), on his return to India in 1785 Farmerwas awarded his first post as Chief, at Fort Victoria, a very small settlement, sixty miles from Bombay, definitely not a lucrative posting. The Chiefship he really wanted and seemed to think he had earned was that of Surat. But when Ramsay, its Chief, resigned early in 1787, John Griffiths, William’s junior, already at Surat as Ramsay’s deputy, was appointed to the post, something of which William complained bitterly in a letter from Fort Victoria in February 1787.[16] He protested in vain; his next posting was the Chiefship of Tannah on the Island of Salsette, all now part of the city of Bombay.

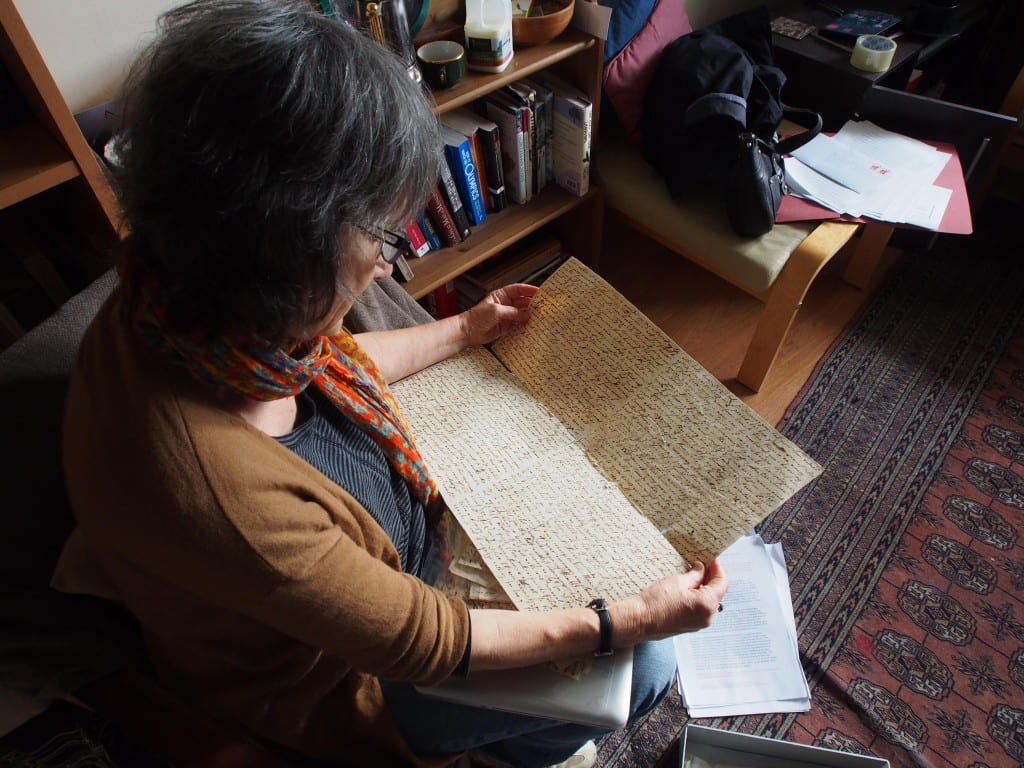

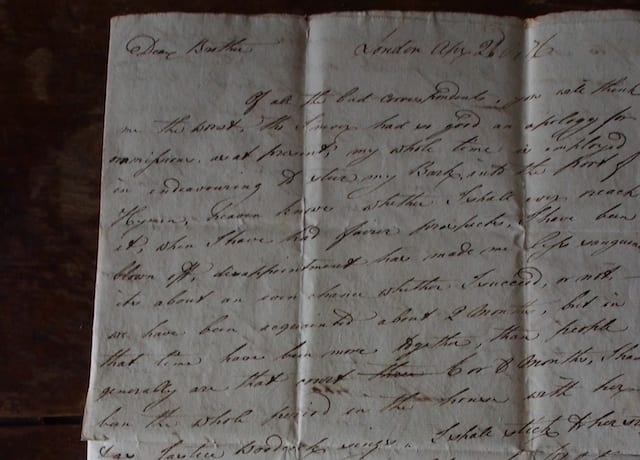

Tannah where William remained between 1789 and 1792 was not much more profitable than Fort Victoria, though it did produce the first surviving family letters for eleven years: two from William to Sam (3 July, December), in handwriting by now much deteriorated. Here William shows himself the old India hand, advising newcomers on how to get on in India. Of one boy he says: ‘the best thing for him is to leave him some years where he is as that will form him to the habit and knowledge of public business whereas removing a young man from Bombay tho it betters his present income generally renders him indolent and ignorant for ever from the want of sufficient occupation.’ Another boy he has taken with him to Tannah, ‘which will keep him from bad company and bad habits most of all which prevail in a large and mixed company.’ This was also the boy he had taught Persian. He still talks of coming home – if all comes through he hopes to return with £15,000, which together with his inheritance, he considers would be sufficient to live on comfortably. In one letter he provides the usual list of requirements – thin pairs of shoes, thick ones, boots (very precise here: ‘military boots that is without tops, the same all the way up, waxed leather, buckram will not do.’) He also requested bottles of some stuff called ‘Dalbrosian’ and more of ‘Chary’, tincture of Bark – i.e. quinine. Sam is clearly still ready to provide everything his brother asks for. This demonstrates yet again how close and how necessary the brothers were to one another.’

Nor was Sam’s support for William merely practical. He had, it seems, commiserated with William on being passed over for Surat, for William responds in relatively philosophical mode. ‘If it had been my destiny I should have had Surat, as it was your manners were certainly very proper’ (December 1789). Sam’s concern is reciprocated in William’s affectionate and equally concerned reference to his admirably docile sister-in-law of whom he was clearly fond. Elizabeth is no longer living above the business in Hogg Lane or even in Mortimer Street in the West End where Sam appears to have acquired a house at some point. For by now Sam also possesses a country estate, his income from a successful dye business having been added to by his ventures in the slave trade.[17] Elizabeth’s only son was now of an age to be off at boarding school and her husband wasstill working in London, butshe does not seem to be flourishing out there in the new home. William writes of the fear Sam has given him for ‘my sister’s health…..I am afraid she keeps too much in the house or perhaps you have now planted Beckenham which precludes proper air or perhaps you are too solitary in the country. I will cure her when I come back again and make her ride out …. I am much younger than when I left England and have much better spirits.’ (December 1789).

[1] General letter to Bombay 1762, OIR/E/4/33, British Library.

[2] Even in the 19th century, European death rates in India remained high. See Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

[3] Carsten Niebuhr, Travels through Arabia and Other Countries in The East, (1763), Volume 2 p. 375.

[4] Personal Records, IOR/ J/1/432, p. 367, British Library.

[5] See Peter Marshall, East Indian Fortunes (Clarendon Press 1976). For trade and risk in India in this period, see Holden Furber, John Company at Work: A Study of European Expansion in India in the Late Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948), and Huw Bowen, The Business of Empire: The East India Company and Imperial Britain, 1756-1833 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[6] Nightingale, Trade in Western India, p. 79.

[7] See esp. Durba Ghosh, Sex and the Family in Colonial India: The Making of Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[8] OIR Personal Records II, p. 83, British Library.

37 Selections from the letters, despatches and other state papers preserved in the Bombay Secretariat: Home Series. Ed Forrest (Bombay, Government Central Press 1887), p.197.

[10]IOR/P/E/6: 1793 pp. 58-66, British Library.

[11]IOR/L/L/2/21, British Library.

[12] Edward Moor, The Hindu Pantheon (London, 1810), note p. 359.

[13] Forbes, Oriental Memoirs, Vol II, p. 548.

[14]IOR/P/D/65, p.342, British Library.

[15] James, Rennell, Memoir of a Map of Hindostan: or the Mogul Empire (London, 1788), p. 148.

[16] Nightingale, Trade and Empire, p. 74.

[17] See An Account of the Number of Vessels, with the Amount of their Tonnage, their Names, the Port to which they belong, and the Names of the respective Owners of each, that have cleared out from the Ports of London, Bristol and Liverpool, to the Coast of Africa, for the Purpose of purchasing slaves, in the Three Years preceding the 5th of January 1792. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the Eighteenth Century, Vol. 82, pp. 329-37.