Two questions: motive and opportunity

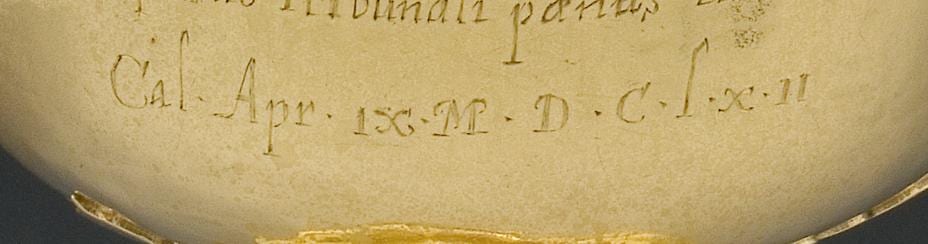

Two questions remain in deciphering the gold cup’s inscription. First, the meaning of ob vitam multifariâ Dei misericordiâ ibidem conservatam [‘on account of his life having been saved there by the manifold mercy of God’]. Second, the date: Cal. Apr. IX. M.D.C.L.X.II [9 April 1662].

Life was certainly precarious in Guinea at the best of times but we can only speculate on the reason for Davies’s gratitude at his own preservation. The vast majority of white residents were temporary and considered themselves lucky to get out alive. Conflict, with Europeans and the Dutch in particular rather than Africans, was a significant source of risk, as were accidents such as storehouse fires. Thomas Chappell, brother of the Agent Roger, died in June 1661 after a fire at Cape Coast factory, one of three major fires there.

Mortality was very high mainly because of disease. For example, Edmond Child arrived on 21 January 1659/60, asked to return in April 1660 because of ill health, and died the same year. John Orme and John Saxby arrived on 17 June 1660 and died on 10 and 15 July that same year. Of Davies’ predecessors as Agent, James Conget was in Africa from April 1653, Chief at Fort Cormantine from July to December 1658 and returned to England in October 1659 because of ill health, from where he went straight on to Barbados. Roger Chapell was in Africa from December 1658 to September 1660 and was permitted to return to England because of ill health, only to return twice in 1663 and 1664. Edmund Young arrived in December 1661 and died there on 23 May 1662. John Puleston came as a factor in May 1662 and died there as Agent on 6 January 1662/63. On 29 May 1662 the Agent and factors at Cormantine wrote to the Court of Directors about ‘the Sad Mortality that hath beene Amongst vs This yeare’ and attached a list of their sixteen colleagues who had died between 18 March and 23 May, with one other bed-ridden and not expected to live. There had likewise been ‘a greate Mortality amongst the flemans [Dutch].’[1] This period includes the date on the Welshpool cup, suggesting that recovery from a serious illness could well have been the motive behind Davies’s grateful donation to his native parish.

The double problem with the date is that in April 1662 Davies wasn’t in fact Agent general as the cup’s inscription states; and being in Guinea he had no opportunity to commission the cup himself. It is feasible that he commissioned the cup by proxy, as the East India Company records show that it was common practice for factors and agents to acquire gold on their own account and to ship it back to England or onward to India. Although there appears to be no record of it, Davies may have done this himself. A minute of the East India Company’s Court of Committees dated 5 February 1663/64 does refer to a parcel of gold of about 42oz belonging to the late Nicholas Herrick sent by Thomas Davies by way of Barbados into the keeping of the Governor and Deputy.[2] Another minute of the Committee for Debts (31 July 1666) mentions a ‘parcel of gold received from Mr. Davis, the Company’s agent in Guinea, which is pretended to belong to the account of the late Jeremy Sapster now in dispute’.[3] However, given the time delay involved, it seems unlikely that Davies ordered the cup to be made while he was in West Africa and more likely that he commissioned it on his return in 1663, adding to it the earlier date of an event he wished to commemorate. Likewise, the memorial at Lathbury church must also be a retrospective commission, given that his father died on 20 November 1661 (ten days after Thomas sailed for Guinea) but the inscription refers to Davies as AGENT GENERALL FOR THE ENGLISH NATION VPON THE COAST OF AFFRICA.

[1]Ibid., p. 116.

[2]Sainsbury (ed.), Calendar of the Court minutes, 1664-1667 (1925). Herrick was conceivably the Levant merchant who was the son of London goldsmith Nicholas Herrick (1542-1592), brother of the poet Robert Herrick (1591-1674) and nephew of the royal goldsmith William Herrick (1562-1653). Helen Clifford, ‘Herrick, Nicholas (1542–1592)’; Michael Mullett, ‘Heyrick, Richard (1600–1667)’; G. E. Aylmer, ‘Herrick , Sir William (bap. 1562, d. 1653)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 (http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/54563; http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13175; http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13076, accessed 11 June 2014).

[3]Sainsbury (ed.), Calendar of the Court minutes, 1664-1667 (1925), p. 240.