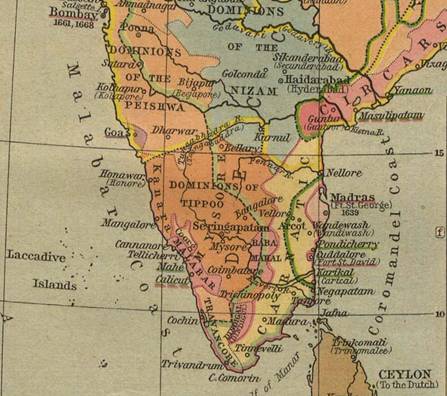

The Walsh family’s relationship with the Company began in the early eighteenth century when Joseph Walsh (d.1731) was appointed senior merchant in Madras. Working in this role gave Joseph access to mercantile connections across India and Europe. In addition, Joseph increased his family’s connection to the Company for future generations when on 27 December 1721 he married Elizabeth Maskelyne (1677-1734) in Madras.[1] Elizabeth Maskelyne was sister to Jane and Sarah and daughter of Nevil Maskelyne (1663-1711) of Purton, Wiltshire. The Maskelyne family later became further linked to the EIC through Nevil’s nephew Edward who worked for the Company and his niece Margaret, who married Robert, first Baron Clive. Joseph and Elizabeth had three children, Joseph (1722-c.1729), John (1726-1795) and Elizabeth (1731-1760?). In 1728, just two years after the birth of their second child, Joseph decided to leave India. He had begun to experience financial difficulties and travelled to London with their eldest son Joseph in an attempt to resolve them. While in England, however, young Joseph contracted smallpox and died. The elder Joseph returned to India alone in 1729 and died there, just two years later in 1731, just before the birth of his last child, Elizabeth.

The Walsh family’s relationship with the Company began in the early eighteenth century when Joseph Walsh (d.1731) was appointed senior merchant in Madras. Working in this role gave Joseph access to mercantile connections across India and Europe. In addition, Joseph increased his family’s connection to the Company for future generations when on 27 December 1721 he married Elizabeth Maskelyne (1677-1734) in Madras.[1] Elizabeth Maskelyne was sister to Jane and Sarah and daughter of Nevil Maskelyne (1663-1711) of Purton, Wiltshire. The Maskelyne family later became further linked to the EIC through Nevil’s nephew Edward who worked for the Company and his niece Margaret, who married Robert, first Baron Clive. Joseph and Elizabeth had three children, Joseph (1722-c.1729), John (1726-1795) and Elizabeth (1731-1760?). In 1728, just two years after the birth of their second child, Joseph decided to leave India. He had begun to experience financial difficulties and travelled to London with their eldest son Joseph in an attempt to resolve them. While in England, however, young Joseph contracted smallpox and died. The elder Joseph returned to India alone in 1729 and died there, just two years later in 1731, just before the birth of his last child, Elizabeth.

After his father’s death in 1731, five-year old John (Joseph and Elizabeth’s second son) was sent to England to be raised by his uncle John Walsh, a merchant living in Hatton Gardens, London. Elizabeth and her daughter Elizabeth remained in Madras, but in 1734, Elizabeth Walsh went into decline and on 24 November she was buried in the city.[2] Her daughter Elizabeth was just three years old and at this point it seems likely that her mother’s sisters Jane and Sarah Maskelyne took her into their care in England.[3]

Despite leaving India at such young ages, both the Walsh children created paths that led them back to the country and to further develop their connections with it and the EIC. In 1742, at the age of 16, John followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the Company as a writer. His first posting sent him to his birthplace, Madras. Five years later, John returned to England and rose (like his father before him) to the grade of senior merchant. In 1749 John Walsh travelled to India once more, this time with his sister Elizabeth who was only just eighteen.

Embarking on such a journey while so young and in a position of relative vulnerability under the care of her twenty-three year old brother must have been a daunting prospect for Elizabeth. In India, Elizabeth Walsh worked to make sense of what she saw, heard, smelt, tasted and touched. She frequently wrote back to her aunts, describing her experiences. Such correspondence provides us with a means by which to interpret Elizabeth’s early life in India. Notably, in her letters, Elizabeth primarily used England as a reference point with which to make sense of her new experiences. It is perhaps unsurprising that in writing to relatives in England, Elizabeth situated her readers by using reference points, which they would understand. Nevertheless, it is significant that Elizabeth particularly focused upon Indian buildings to make sense of her new environment. For instance, in her letters, she made frequent reference to the houses in which she stayed. On arrival she noted that the first house she stayed in was more like a ‘barn’.[4] In comparison the Company house she shared with her brother in Madras was much more comfortable, Elizabeth described it as ‘a little palace’.[5] The social world into which she stepped also required description and she noted how with such limited sociable company ‘it is just like living in a County town in England’.[6] In describing India to her aunts Elizabeth greeted their desire for knowledge with a sense of humour based on their shared, intimate knowledge of England. For both those in India and at home, the central means of navigating these new experiences was through a shared knowledge of English social and cultural life.

Shift, England, 1730-1760, Linen, hand sewn, T.26-1969. V&A. The shift or smock, was worn to protect outer clothing from the body, in an age when daily bathing was not customary. Made of very fine linen, the shift was the first garment put on when dressing.

The social world of Madras would have greeted the Walsh’s favourably as they benefitted from their relation to certain family members already established in the city. When in 1750 Elizabeth Walsh moved to be with her brother in Madras, their first cousin once removed (Edmund Maskelyne) was already stationed there. As a close friend of Robert Clive, Edmund was well established within the East India Company network. While stationed in Madras, therefore, both John and Elizabeth became increasingly involved in Company life. Elizabeth met and began a relationship with Joseph Fowke (1716-1800). Like Elizabeth, Fowke was born in Madras and probably travelled to England in around 1728 with his father. He had returned to Madras in 1736 to begin work for the East India Company as a writer and by the time he met (or re-met) Elizabeth had risen to the rank of third in council. Elizabeth promptly married Fowke in May 1750, just one year into her time in India.[7]

Despite establishing herself in India through her social network and new marriage, Elizabeth continued to fixate on England. She worked hard to maintain her connections with home, regularly sending gifts of textiles to members of her family. For example, she sent a package containing a dozen shifts (see right), sixteen white pocket handkerchiefs and four gingham gowns to her aunts Jane and Sarah Maskelyne in September 1750.[8] In sending these gifts, Elizabeth engaged in a culture of gift giving, which reaffirmed her affective position within a larger kin network.[9] She also provided her kin with material evidence of her current life, which created a further set of shared reference points.[10]

Nevertheless, after two years in India Elizabeth remained homesick for England. Writing to her aunts, Elizabeth warmly described how the house she lived in had ‘a view of the sea.’ Yet, in spite of such benefits and her enjoyment of the climate in India, she asserted that ‘as for everything else give me old England’.[11] Elizabeth’s words are imbued with a distinct and poignant sense of longing for something distant and perhaps lost. What constituted ‘old England’ in Elizabeth Fowke’s mind’s eye? Did she refer to her old England, the England she had enjoyed while growing up? This was an England that now appeared in both geographical and temporal terms to be at a great distance. Or did she refer to ‘old England’ in a more historical and romantic sense? Perhaps Elizabeth longed for a simpler Merrie old England?

Johannes Hofer, a Swiss doctor, coined the term ‘nostalgia’ in his medical dissertation of 1688. He asserted that nostalgia defined “the sad mood originating from the desire for return to one’s native land”.[12] In the seventeenth century this newly defined disease constituted a single-minded obsessional longing for the native land and is particularly associated with Swiss soldiers fighting abroad. Where do Elizabeth Fowke’s longings for England fit within this wider experience of nostalgia? Lacking single-minded obsession her longing does not appear to have manifested itself in such terms. But her longing for a lost time and lost home are evident in her letters and need to be noted, particularly in the context of her future family. Soon, however, Elizabeth’s longing was sated and her wishes were met – she returned to England with her husband in 1752.

Elizabeth was not alone in holding to England’s houses, landscape and social life as her main reference points, as other case studies show (see for example Warren Hastings’ nostalgia for the English country house while in India in the Daylesford Case Study – currently unavailable). Moreover, individuals employed England as a reference point in the descriptions contained in their correspondences, not only to offer their readers a means of sharing their experiences, but also as a way of expressing their own ‘home’. For Elizabeth Fowke, England represented something simpler than her present situation, something known and understood. At the same time, her longing for an entity as broad as ‘England’ appeared vague and uncertain. In contrast future generations of the Walsh family, particularly Elizabeth’s daughter Margaret, would experience a much clearer idea of what they longed for while away in India. As this case study goes on to show, Margaret longed after a particular home, a specific country house in fact, named Warfield Park.

Return to Warfield Park Case Study Menu / Next

[1] BL IOR N/2/1 f.42.

[2] BL IOR N/2/1 f.42.

[3] In later life, Elizabeth frequently wrote very open letters to her aunts suggesting a real intimacy between them.

[4] British Library, India Office Records, European Manuscripts, Letter from Elizabeth Walsh to Jane and Sarah Maskelyne, D546/2, 10 October 1749, p. 11.

[5] Letter from Elizabeth Walsh to Mrs Jane and Sarah Maskelyne, 1 Feb 1749, D546/2, p. 15.

[6] Ibid.

[7] British Library IOR N/2/1 f.246.

[8] Letter from Elizabeth Walsh to Mrs Jane and Sarah Maskelyne, 13 September 1750, D546/2, p. 19.

[9] Margot C. Finn, ‘Colonial Gifts: Family Politics and the Exchange of Goods in British India, c. 1780-1820’, Modern Asian Studies, 40:1 (2006), p. 221.

[10] Russell W. Belk, ‘Moving Possessions: An Analysis Based on Personal Documents from the 1847-1869 Mormon Migration, The Journal of Consumer Research, 19:3 (1992), p. 354. Belk’s research found that female Mormon migrants sent home samples taken from their new clothes to show geographically family members what they were wearing. There is no evidence of this among East India Company families, but the desire to send home materials could be seen as activated a similar process of knowledge sharing.

[11] Letter from Elizabeth Walsh to Mrs Jane and Sarah Maskelyne, Feb 1751, Eur D546/2, p. 32.

[12] Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), p. 3.