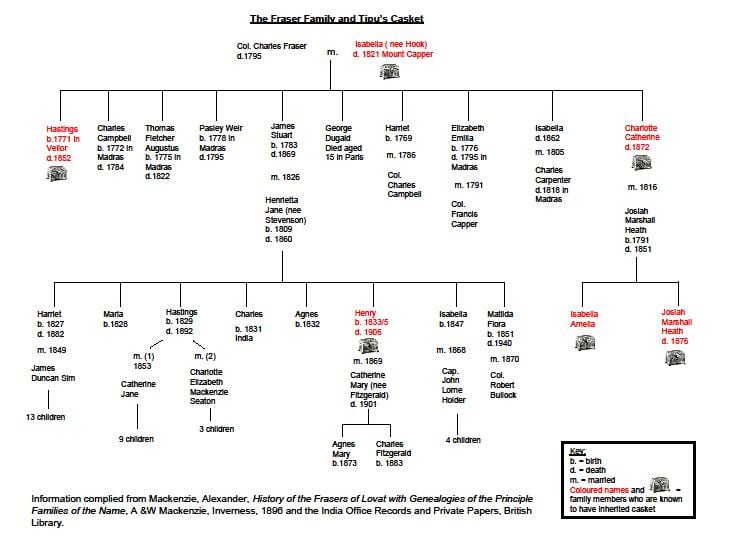

The casket was donated to the British Museum by Col. Henry Fraser in 1904 and the references in the documents allow us to trace its journey from Seringapatam to the Museum via various members of the Fraser family. The ‘Uncle Fraser’ to whom the first note refers and who acquired the casket is General Hastings Fraser, mentioned by Major Alexander Allan in his account of the battle.[1] Fraser was one of ten children of Captain Charles Fraser and Isabella Hook. Charles Fraser had previously served in the Marines and joined the East India Company in 1762 taking his first post in Madras.[2] He returned on leave in 1768 when he and Hook married and they returned together to Madras the following year. Their eldest child, born in 1771 at Vellore, was named Hastings “in acknowledgement of several acts of kindness rendered to the father by Warren Hastings”, then member of the Council at Madras.[3] The future Governor-General wrote to the parents thanking them for this honour offering the gift of a shawl. Charles died in 1795 while acting as General of Division of the Company Army. His widow Isabella lived for a further twenty-six years, dying at Mount Capper, Cuddalore in 1821. To read the Fraser family tree in PDF format, click here.

Photograph of old Capper House from The Hindu in 2007 which describes how after becoming part of Queen Mary’s College, it fell into disrepair and was gradually dismantled: http://www.hindu.com/mp/2007/10/22/stories/2007102250230500.htm Accessed 11 May 2012.

Of their ten children, three died before reaching adulthood – one, Pasley Weir, drowning on the way to join his father as a cadet in India. Their eighth child, Elizabeth Fraser, aged only 15, married Colonel Francis Capper in 1791. Although Elizabeth died without issue in 1795 the families appear to have remained closely connected.[4] Francis Capper commissioned the Capper House to be built around 1800 at Cuddalore.[5] It was the heart of the army campus and the first residency constructed on the beachfront north of St Thomé.[6] The reference within the first document accompanying the casket suggests that Isabella Fraser moved into the house during her widowhood.

The house at Mount Capper seems to have been the centre of family activity. Charles and Isabella’s ninth daughter, also named Isabella, married there in 1805 to Charles Carpenter (brother of Charlotte Carpenter who in 1797 married the novelist Walter Scott, who himself admired Tipu Sultan, remarking that he possessed greater resolve and “dogged spirit of resolution” than Napoleon, dying “manfully upon the breach of his capital city with his sabre clenched in his hand”.)[7] Their youngest daughter, Charlotte Catherine, also married at Capper House in 1816 to Marshall Heath – also referred to in the first document.[8]

Hastings Fraser, the original acquirer of the casket, distinguished himself within the army after joining in 1788, rising to a high rank before 1799. In 1797 he sailed to Penang on the abandoned Manilla expedition and became a captain later that year. He was only 28 when he led his regiment against Tipu Sultan in 1799. As mentioned in the document with the casket, he was nominated as one of the Prize Agents who were tasked with distributing the treasury of Tipu Sultan. The note records that, of the items he himself received, he sent this “silver coffer … from Tipoo’s own room”, a silk carpet and a string of coral beads (the ‘chaplet’) to his mother at Capper house.

Hastings Fraser’s fine leadership at the taking of the Island of Bourbon (Réunion Island) in 1810 was recognised by his own corps, who presented him with a valuable sword, and the so-called native regiments, who gave him a silver plate. These were the first items mentioned in his will where Hastings Fraser bequeathed them to his brother James with instructions that they were to be passed on to his nephew (James’s son) and namesake.[9] He died after receiving several military offices in 1852 in London, aged 83, unmarried.[10]

Charles and Isabella Fraser’s fifth son, James Stuart, who inherited the estate on Hastings’s death, was also a distinguished East India Company officer, who at one stage was responsible for transporting the Princes of Mysore (the descendants of Hyder ‘Ali and Tipu Sultan whose household, as Margot Finn has shown, was a complicated and expensive undertaking for the Company) to Bengal in 1807. Rising to the position of British Resident at the Court of the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1839, he remained in India until 1853 after resigning the previous year due to a disagreement with the Marquis of Dalhousie over the Company policy of expansion into Berar. His marriage to Henrietta Stevenson, daughter of another significant Company family, had also taken place at Cuddalore. Of their eight children, Hastings was the eldest, named after his uncle discussed above. It was their third son Henry who finally received the casket.[11] Their fourth daughter Harriet, one of their five daughters, had thirteen children – several of whom served in imperial territories.

Before the casket came into Henry Fraser’s hands, the document indicates that Marshall and Charlotte Heath’s son, Josiah Marshall Heath received the casket from Charlotte. Josiah spent his early years in India and was notable for his attempt to establish iron and steel manufacturing plants in the Madras Presidency.[12] It was Josiah who felt it appropriate that Henry Fraser receive that casket, which we learn from the document was undertaken by his sister Isabella Heath. This Isabella is the author of the second of the documents accompanying the casket. Her letter, though undated, notes the intriguing detail that it was Henry Fraser who observed the ‘Hyder ‘Ali’ stamp. As discussed earlier, this stamp is minute and would have required a magnifying glass and expertise in reading in Persian script to decipher. We can then infer that the object was not only a ‘family relic’ with anecdotal history attached, but also one which was subject to close scrutiny by its new owner, a source of fascination and perhaps pride, beyond being an exquisite piece of craftsmanship. Its enduring association with the celebrated Indian rulers and its particular passage between different family members – both male and female – suggests that it came in some respects to symbolise the family’s multiple connections with the empire in India. Isabella Heath’s letter implies that ‘relics’ from Seringapatam retained their emotive power to their British owners well into the late nineteenth century.

Henry Fraser did not donate any other objects to the BM and within the scope of this research, we have found no other references to objects donated by him to other institutions. In the absence of further evidence, we must be wary of drawing more than tentative conclusions. However, certain elements stand out. The fact that the casket was not simply passed down from one generation to another – in fact it was passed specifically to cousins to whom it was deemed of interest or relevance – suggests that it had heightened importance. Unlike a sword which might have automatically been passed between male relatives, this object was given first from son to mother, then mother to daughter, to her son, to his sister and finally to their male cousin. The enthusiasm by Lady Clive to acquire objects after Seringapatam suggests that collecting this material was taken up by men and women alike. The casket seems not to have acquired a specifically gendered meaning – a delicate and exquisite piece of craftsmanship designed to hold scented oils, bound up with a narrative of battle, bloodshed and empire-building.

[1] Major Allan’s Account of his Interview with the Princes in the Palace of Seringapatam, and of finding the Body of the late Tippoo Sultaun in Beatson, A. A View of the Origin and Conduct of the War with Tippoo Sultaun; comprising a narrative of the operations of the army under the command of Lieutenant-General George Harris, and of the siege of Seringapatam (London: G. & W. Nichol, 1800). Appendix No. XLII pp. cxxvii-cxxxi.

[2] Alexander Mackenzie, History of the Frasers of Lovat with Genealogies of the Principal Families of the Name: To Which Is Added Those of Dunballoch and Phopachy (Inverness: Mackenzie, 1896), p. 656.

[3] Ibid., p. 657.

[4] According to the Hindu article, Francis Capper was also a noted geographer.

[5] Henry Davis Love, Vestiges of Old Madras, 1640 – 1800 (London: John Murray, 1913), pp. 70-1.

[6] Ibid., p. 71.

[7] Written in 1814 at the time of Napoleon’s abdication, quoted in Iain Gordon Brown, ‘Griffins, Nabobs and a Seasoning of Curry Powder: Walter Scott and the Indian Theme in Life and Literature’, in The Tiger and the Thistle: Tipu Sultan and the Scots in India, 1760-1800, ed. Anne Buddle (Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland, 1999), p. 79. See also p. 76-7 for details of Scott’s interaction with the Carpenter family.

[8] The Edinburgh Annual Register for 1816, Vol. 9 (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable Co., 1820) p. ccccxvi

[9] The National Archives: PROB 11/1082/388 ‘Will of Hugh Fraser, Commander of the Ship Hastings in the Honourable East India Companies Service’.

[10] Hastings Fraser’s grave is in Kensal Green cemetery in London. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=71385081&PIpi=43951669 accessed 15 April 2013.

[11] Hastings was notable for his service in Hyderabad and his attention to improving living conditions for local people: Mackenzie, History of the Frasers of Lovat with Genealogies of the Principal Families of the Name, p. 669.

[12] Shyam Rungta, The Rise of Business Corporations in India, 1851-1900 (Cambridge: University Press, 1970), p. 276. See also Thomas Webster, The Case of Josiah Marshall Heath, the Inventor and Introducer of the Manufacture of Welding Cast Steel from British Iron (London: W Benning & Co, 1856).