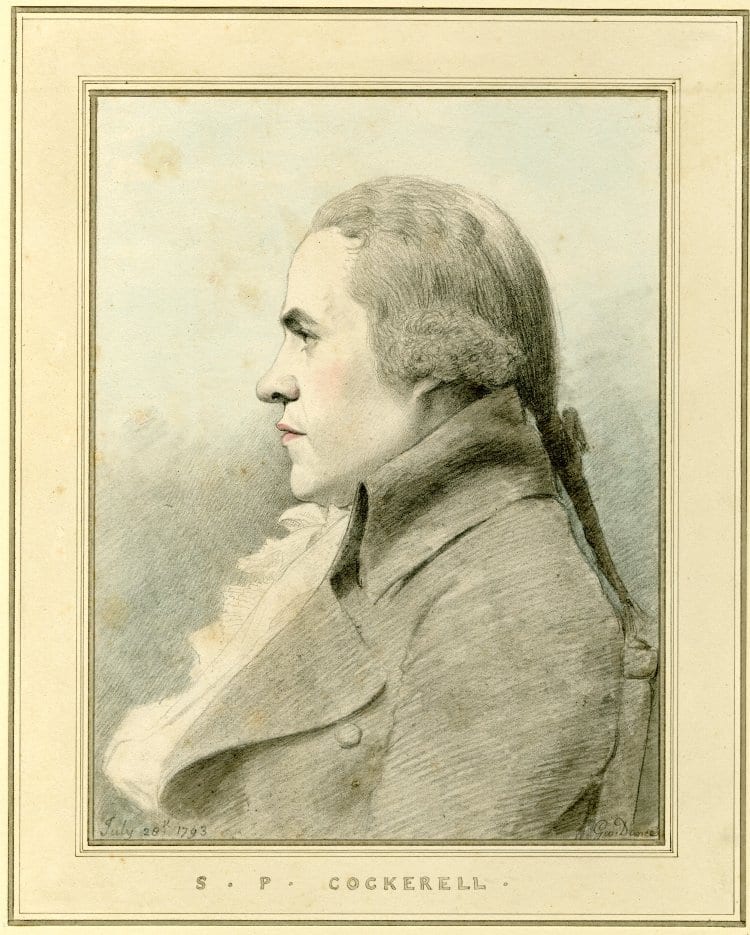

Figure 8: Portrait of Samuel Pepys Cockerell by George Dance. 1793 Graphite, with watercolour. Museum number 1898,0712.17. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Cockerell Family

Sezincote’s association with the Cockerells and the East India Company began in 1795 when Colonel John Cockerell (1752 – 1798) purchased the estate just prior to his retirement from the Company’s military service. [1] Correspondence between John and his brother, Samuel Pepys Cockerell (see figure 8), documents the purchase of the estate from the Earl of Guildford.[2] John Cockerell arrived home from Bengal in 1794 after a long and distinguished military career with the East India Company’s (EIC) army. He first went to India in 1763, aged fourteen, and was attached to the household of General Sir Robert Barker, Commander-in-Chief at Bengal. In 1776 Cockerell was appointed to the military staff of Governor-General Warren Hastings – an association that may explain, in part, his choice of Sezincote, due to its proximity to Daylesford, Hastings’ home a few miles away. We have already seen in Georgina Green’s study of Valentines Mansion that employees of the EIC tended to settle in areas where former Company colleagues, or relatives with EIC connections had chosen to live. John’s sister Elizabeth Cockerell was married to John Belli, Hastings’ private secretary and agent for the supply of provisions to the garrison in Fort William.[3] Charles Cockerell’s former sister-in-law, Charlotte Blunt, married Charles von Imhoff, Warren Hastings stepson: Company loyalty and family connections were clearly important. [4

John Cockerell’s final years in India were spent attached to the staff of Lord Cornwallis, Governor-General of India, for whom he commanded troops, in the Mysore Wars against Tipu Sultan. [5] He returned to London in 1794, bringing with him his Indo-Portuguese mistress, Estuarta, who chose to settle in Brighton with their children rather than in London.[6] Although it was not unusual for the children born of the relationships between British men and Eurasian women to be baptised as Christians and educated in England, it was unusual for the mothers to travel as well. As Christopher Hawes notes, there was a ‘tacit understanding that such partnerships were for India only’ and ‘save for a very few cases, when British men returned home the Indian companion stayed in India’.[7] John Cockerell made no provision for Estuarta in his will, leaving the bulk of his estate including Sezincote to his sister and two brothers.[8] An indenture dated September 1795, had requested that the property pass to Samuel Pepys Cockerell to ‘prevent any wife of the said John Cockerell from being entitled to Power in any part of [the] premises after [the] death of John Cockerell’, but the codicil to his will, dated 1795, simply states that ‘Seasoncote’ be treated the same as his other property and effects and be left in equal shares between his two brothers and sister. [9] However, Cockerell did leave the sum of eighty thousand rupees to be shared between his natural daughter Sophia Johnson (b.1782) and his natural sons John (b.1783), Charles (b.1785) and Samuel Johnson (b.1790).[10]

Although Estuarta appears to have been denied all claims to the Cockerell estate, she remained under the guardianship of the family, sometimes staying with John’s sister Elizabeth and her husband in Southampton, where John Cockerell often visited her.[11] She was also, on occasion, the guest of Samuel Pepys Cockerell in London.[12] Estuarta’s journey to England represents a larger story of empire’s impact on domestic Britain. It is indicative of cultural exchange in its most physical and human form and warrants more attention than there is room for within this case study. The same is true for the fate of the children. This history, absent from the ‘public’ face of Sezincote, is recreated by an examination of the Cockerell family’s private, domestic papers.

A Jacobean gabled manor, Sezincote, in 1795, was in much need of repair and renovation, and John Cockerell commissioned his brother, Samuel Pepys Cockerell, to develop and alter the house, outbuildings and estate. The intention at this time was to keep the alterations simple, within a primarily European idiom.[13] Writing to his agent, Walford (Hastings’ local agent was also Walford, probably the same person), in Banbury, Oxfordshire, John Cockerell said he had ‘many conceits and fancies in regard to Seasoncote for a residence’ yet he was looking for workman to furnish ‘the plain sort of work I shall mostly want.’[14] Raymond Head suggests that although John Cockerell wished to be seen as a respectable gentleman, with a ‘house, carriage, a few servants and a gardener so that he could “embrace some Eligible, tho’ moderate systematic Establishment”’, he was not interested in the ‘extravagant, pampered display commonly expected from a nabob’.[15] Sezincote was, nevertheless, a country manor house with land much like the country seats acquired or built by other returning employees of the East India Company. John Cockerell, however, died in 1798, before the alterations were fully complete and the Sezincote estate passed to his brothers, Charles and Samuel Pepys and sister Elizabeth. In 1801, Charles Cockerell bought the shares of his siblings for a total of £38,000 and it was during his tenure that Sezincote was transformed into an ‘Indian House’. [16]

Charles Cockerell had also had a long and distinguished career in the service of the East India Company, beginning as a writer in 1776 for the Surveyor’s office in Bengal and progressing to become Postmaster General in Calcutta in 1784. He remained in this post until 1792, thereafter staying in India and in the service of the Company but without official employment, devoting much of his time to his own private business.[17] Both John and Charles were involved in private trade in India. Correspondence from John to Charles, now held at the Bodleian Library, refers to the brothers’ business transactions. These documents include Bills of Exchange drawn on third parties to circumvent the Company’s punitive rules surrounding the transfer of personal funds and details of the purchase of precious stones. Charles was also a partner in the agency house established by William Paxton (1744 – 1824). Paxton was assay officer and Master of the Mint in Bengal from 1778, a position which afforded him the opportunity to conduct his private business interests in facilitating the transfer of funds to Britain for other nabobs, allowing him to amass a considerable personal fortune.[18] When Paxton returned to England Charles took over the management of the agency house in Calcutta, which became Paxton, Cockerell and Trail, the most successful agency house of the period – it is in this activity that Charles appears to have amassed his fortune.[19]

In 1789 Charles married Maria Tryphena Blunt, the daughter of Sir Charles William Blunt, another employee of the Company; Maria died, childless, later that year and Charles remained a widower until 1808 when he married the Hon. Harriet Rushout, daughter of John Rushout, first Baron Northwick. The couple had two daughters and one son. Upon his return to England in 1801, Charles became a partner in the London office of Paxton, Cockerell and Trail, conducting business for clients in India and England. His personal interests extended beyond the company: he was a director of the Globe Insurance Company, the Arkendale and Derwent Mining Company and the Gas, Light and Coke Company. He maintained his connections to India and the Company, remaining a stockholder and serving as a commissioner on the Board of Control for India between 1835 and 1837.[20] Charles was close to Richard, Marquis of Wellesley, Governor-General of India from 1797 to 1805, having assisted him with financial arrangements during the Mysore war of 1799 and by commanding the military force raised within the civil service during this war.[21] His relationship with Wellesley appears to have been symbiotic, with Charles acting as creditor for him and Wellesley supporting his baronetcy in 1809.[22] Charles’ political career began in 1802 when he became MP for Tregony in Cornwall, eventually becoming MP for Evesham (having previously been Mayor) in 1819 until his death in 1837.[23]Coming from a relatively humble background Charles Cockerell was perhaps the epitome of nabobs as ‘upstarts with vast, easily won fortunes’, which they would use to ‘advance their social and political influence’.[24]

[1] John, Charles, Samuel Pepys and Elizabeth Cockerell were descendants, through their mother of the diarist Samuel Pepys.

[2] Allen Firth, The Book of Bourton-on-the-Hill, Batsford and Sezincote: Aspects of a North Cotswolds Community (Tiverton: Halsgrove, 2005), pp. 49-66 and pp. 77-98; Head, ‘Sezincote: A Paradigm of the Indian Style’, pp. 15-16.

[3] The Defence of Warren Hastings, Esq. (Late Governor General of Bengal) at the Bar of the House of Commons (London: 1786), p.137.

[4] In fact, during a period of leave in England, Charles Cockerell gave evidence in Hastings’ trial. See Meike Fellinger,‘”All Man’s Pollution Does the Sea Cleanse”: Revisiting the Nabobs in Britain 1785-1837’, Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Warwick 2010, http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/emforum/projects/disstheses/dissertations/fellinger-meike [accessed 31 January 2014], pp. 58-70.

[5] The East India Military Calendar Containing the Services of General and Field Officers of the Indian Army (Leadenhall: Kingsbury, Parbury and Allen, 1823), p. 114.

[6] Correspondence and papers of Sir Charles Cockerell and other members of his family, 1774 – 1880. Shelfmarks: Dep.b.254, c.855-6, Bodleian Library, Oxford; letter to Sir Charles Cockerell from John Cockerell, 1794, Dep.c.856.

[7] Christopher Hawes, Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1733 -1833 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), p. 8.

[8] Gloucestershire Archives, D536/T36, Last Will and Testament of John Cockerell, Calcutta, 25 February 1793.

[9] Gloucestershire Archives, 1652, as cited in Head, ‘Sezincote’, p.16; Gloucestershire Archives, D536/T36, Last Will and Testament of John Cockerell, Calcutta, 25 February 1793, Second Codicil, 1795. See Hawes, Poor Relations, chapter 1 ‘British Men, Indian Women, Eurasian Children’ for a discussion of provisions made for the ‘natural’ children of relationships such as John Cockerell and Estuarta.

[10] Gloucestershire Archives, D536/T36, Last Will and Testament of John Cockerell, Calcutta, 25 February 1793.

[11] Head, ‘Sezincote’, p. 17.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 19.

[14] Gloucestershire Archives, D1652, John Cockerell to Walford, November 1797.

[15] Head, ‘Sezincote’, p. 19 and p. 143, n.12.

[16] Ibid., p. 37.

[17]P. J. Marshall and Willem G. J. Kuiters, ‘Cockerell, Sir Charles, first baronet (1755 – 1837)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnp.com [accessed 15 January 2013].

[18] Fellinger, ‘”All Man’s Pollution Does the Sea Cleanse”: Revisiting the Nabobs in Britain, 1785 – 1837’, pp. 47-58.

[19] Marshall and Kuiters, ‘Cockerell, Sir Charles, first baronet (1755 – 1837)’.

[20] Ibid.

[21]http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume1790-1820/member/cockerell-charles-1755-1837 [accessed 20 October 2013].

[22] Ibid. (The Bodleian Library, Oxford holds correspondence relating to financial affairs of Cockerell and Wellesley, but these have not been consulted for this case study.)

[23] Ibid.

[24]Tillman W. Nechtman, Nabobs, Empire and Identity in Eighteenth-Century Britain, p. 161. See also Helen Clifford’s case study, Aske Hall, Yorkshire, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/aske-hall-yorkshire/.