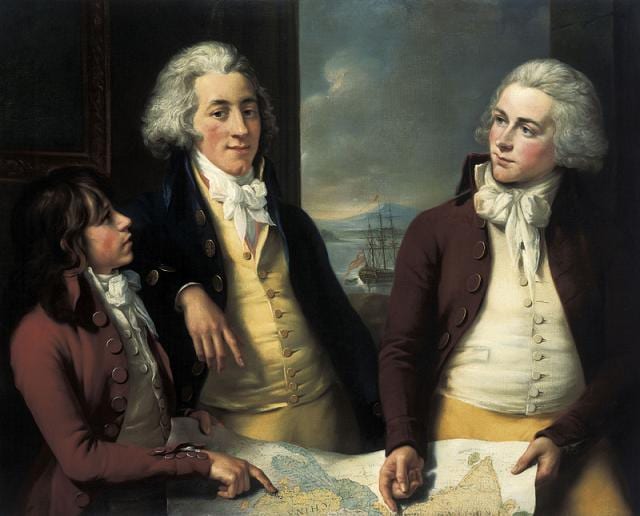

Figure 3: The Money brothers: William (1769-1834), James (1772-1833) and Robert Taylor (1775-1803) 1788-92, by John Francis Rigaud, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, BHC2866.

A group portrait of three sons of William Money (1738-1796), a Director of the East India Company and an Elder Brother of Trinity House, commissioned by Sir Robert Wigram Bt (1769-1830), Money’s lifelong friend and business partner. William Taylor (middle) was a director of the Company in 1811, an elder brother of Trinity House and an MP. He was also knighted and died as Consul General at Venice in 1834. His right arm rests on the shoulder of his brother Robert, who stands to the left and is shown half-length, to right, wearing a red coat. He is in profile looking at his eldest brother and pointing with his right hand to a map of China at the place marked Canton. James, the right hand figure, holds the other end of the map with his right forefinger placed on Calcutta. Through a window behind him the Indiaman ‘Rose’ is shown at anchor. James and Robert both spent their lives in the civil branch of the Company’s service, with Robert serving in China. (Source: NMM’s online image catalogue).

Three generations of the Child family at Osterley, much like the Taylor brothers who are illustrated left, were intimately involved in the East India Company. Unlike many other properties covered by case studies, the EIC Connection with Osterley is almost entirely London based. As far as we know none of the Child family who owned the property in the seventeenth and eighteenth century ever travelled to Asia, or served as employees of the EIC. However, the family was concerned with the governance of the Company at an important stage of its development, accumulating wealth through trading and substantial EIC stockholdings. They were undoubtedly influenced by the tastes and styles of the countries it traded with, and the substantial contribution to their wealth from the stocks they held in the Company gave them the money to furnish their home in that (and the neo-classical) style.

For over 30 years one of the immediate family was a Director,[1] two owned ships leased to the EIC,[2] and all had substantial EIC stockholdings. Two served as Lord Mayor of London,[3] three were knighted and at least one member of the family was sitting as an MP for all but one of the years from 1722-1782. They thus sat, and had influence, at the centre of the political, financial and commercial world at a time when the Company was in its formative phase of growth. And the people they were close to were an integral part of this Company nexus. One partner in the Child & Co Bank, Robert Dent, was a co-owner of at least one of the ships used by the Company;[4]another Thomas Devon, was a critical backer of Sulivan in his fight against Robert Clive for the control of the Company in the 1760s. Sarah Jodrell’s marriage into the family in 1763 reinforced the connection. Two of her family, Daniel Sheldon and Richard Craddock, had served as Company men in India at the end of the seventeenth century, and both later became Directors.

The First Director, Francis Child the Elder (1642-1713)

Francis Child the elder acquired Osterley House in 1713, shortly before his death. The son of a cloth merchant, Francis Child moved to London in 1656 to be apprenticed to William Hall, a goldsmith and eventually became a Freeman of the Company of Goldsmiths in 1665.[5] Around this time, it is known that he went to work for Blanchard and Wheeler, one of the pioneering banker/goldsmiths who had premises in the Strand. When in 1671 he married the daughter of Martha and William Wheeler, who was also a stepdaughter of Robert Blanchard, he inherited their combined fortunes catapulting Francis Child’s status in London society. Blanchard and Wheeler, and its successor business, Child & Co. survived the many pitfalls that befell other banker/goldsmiths at this time and when he died in 1713 Sir Francis Child was a very wealthy man, with assets of £250,000 – assessed by Philip Beresford to be equivalent to £3.8bn today.[6]His jewellery business was one of the largest in London[7]and clients for the banking side of the business included not only the landed gentry such as the Earl of Dorset, a friend and patron but such notables as Nell Gwyn and Isaac Newton.[8]

Figure 4: Francis Child the elder (1641/2-1713) in his robes as Lord Mayor of London. Attributed to Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646 -1723). Image Courtesy: Osterley House, National Trust. Reproduced by kind permission of Christ’s Hospital Foundation.

In 1683 the London Gazette announced that Francis Child was to hold a lottery to dispose of the jewellery of Prince Rupert (grandson of King James 1) at Whitehall. A History of London Goldsmiths describes King Charles II ‘counting the tickets among all the lords and ladies who flocked to take part in the adventure.” [9] Further, Child & Co. archives show that he also regularly advanced large sums of money to the Treasury and later became “jeweller in ordinary” to King William III.[10] It is known that he lent pieces for the coronation of King William and Queen Mary in April 1689, and sold many pieces for their personal use or to give as gifts.[11] In that same year he was made an Alderman, and was knighted by William III.[12]

Edgar Samuel’s research published in the Three Banks Review draws on the bank’s archives to show just how important the jewellery side of the business was to Francis; delegated by Blanchard to another jeweller John East, Francis bought it back under his control in 1681. It may have been this that first ignited his interest in the East India Company, as a source of precious stones. Certainly Sir Dudley North, 1st Lord Guildford is recorded as buying 2000 pieces of eight from Sir Francis Child at 5s 4 and a half p for export to Aleppo.[13] A 1675 stock valuation in his own hand shows a number of designs and his stock of jewellery expanded steadily. In 1690 he valued his stock of loose diamonds at over £5000. In that year he was made Sherriff of London and the following year Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths Company.[14]

As well as using polished stones and recycled gems from second hand pieces he regularly bought large numbers of unpolished diamonds. Diamonds bought from EIC men, such as Captain Chamblett, would be polished and remounted for sale. His partner, John East, had bought rough diamonds from John Joliffe (an EIC Director), Isaac Alvares and Antonio Rodrigues Marques. In 1683/4 Francis bought over £7,000 of diamonds at EIC auctions. In 1686, Francis started to trade as a diamond importer. Adopting the low risk strategy that had served him well as a banker, he initially invested £200 with Streynsham Master, an EIC Company man.[15] The papers of Elihu Yale, Governor of Madras from 1686-1692 show that Francis together with Sir Henry Johnson had sent 5000 pagodas (£2375) to Yale intending to buy diamonds, but which instead was invested in a voyage to Bengal. He continued to invest, often using Abraham Pluymer, a Dutch diamond cutter to do the buying, but later also using a Daniel Chardin in Madras.[16]

The banking side of Child & Co was a rival to the Bank of England, which was set up in 1694. The brainchild of Scottish financier William Paterson, the Bank of England functioned as a source of cash supply for the Government initially advancing it £1.2 million. However, it was in direct competition with Francis Child’s bank, which was making large loans to the Crown and for financing the governing of Ireland and the war with France.[17] His eventual resentment of the Bank of England resulted in an attempt to set up a rival institution called the Land Bank in 1696 and in 1708 Child was accused of attempting to force a run on the Bank of England.[18] Furthermore Child’s involvement with the Old East India Company came into conflict with the interests of the Government, which created a rift between Child and the Whigs. James Vernon, a government Minister is said to have stated ‘the Bank and the New East India Company have spoiled Sir Francis for a good Whig’ when considering his candidacy for Lord Mayor, which was regarded with much ambivalence.[19] Nevertheless in 1698 Francis Child was Lord Mayor of London and was elected to the EIC Court of Directors later in the same year.[20]

Francis Child the Elder and the East India Company

Francis Child had been a substantial stockholder in the Old East India Company with the Company account in Child & Co. bank. He was appointed to the committee set up to finalize negotiations for a merger with the New Company ‘The United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies “provided that it can be done on safe, just and reasonable grounds’[21] and a parliamentary list of early 1700 classed him in the ‘interest’ of the Old East India Company.[22] In 1709 the Old and the new EIC merger became a reality and the United Company was to be run by a Court of 24 annually elected Directors, each of who was a major stockholder in the Company.[23]

Francis Child also sat on the important Committees of Shipping, Private Trade, Books and Accounts and “Writing of Letters”. During this time the Court Minutes of the EIC show that these Committees were responsible for placing orders with Captains and the principal owners of ships for imports and exports, for regulating standards and quality of goods, and of seamanship and safety. Child remained a Director until 1701 and served again briefly in 1711.[24]During his Mayoralty Sir Francis left the buying to his diamond polisher, Joseph Cope, who cut and polished £60,000 worth of rough diamonds between 1698 and 1704 for Francis and his associates.

Picturing Home: Francis Child the elder’s travel to the Netherlands in 1697

The period leading up to Francis Child the elder’s connection with the Old East India Company (and later The East India Company) played an important part in shaping his sensibility for acquiring objects and furnishings for the interiors of his home in London.

Hardly anything is known about Francis Child’s legacy for setting the standards of taste in the family but much can be gleaned from his personal journal, A short account by way of Journal of 10th I observed most remarkable in my travels thro’ some part of the Low Country, Flanders, & some part of Germany whis is on the Rhine recording a momentous visit to the Netherlands in 1697.[25] The journal survives in the collection of the London Metropolitan Archives in two copies in bound notebooks. Sir Francis appears to have been a part of an official delegation to the talks culminating in the Treaty of Reswick that ended the Nine Years War with France and Spain. He accompanied the Earl of Pembroke on this trip and made a pointed note of gratitude in his journal referring to him as ‘…our first Plenipotentiary at this treaty from whom I received beyond what I could have expected.’[26]

Sir Francis made copious notes of his travel, describing the various towns, their mercantile connections and advantages, their urban landscape, churches, sculptures, country houses and gardens. The interiors of the grand mansions he visited made a deep impression on him and his detailed descriptions convey his delight upon beholding the remarkable fruits of mercantile trade between Europe and Asia.

Francis the elder’s description begins with the town of Middleburgh ‘… a rich, populous and beautifull town, has many merchants which trade to all parts of the world, has a share in the East India Company and have during this war sent out many capers whereof some have carried 30 guns…’[27] He goes on to detail the topographical qualities of Rotterdam that affected sea trade between England and the Netherlands:

The great trade it has is owning to the commodious sense of its harbour, for ships of great burthen, can by these canalls not only come into the town and unlode at the Merchant’s door, but in 2 tides return to sea, whereas ships bound to Amsterdam from England, must unlode at the Texell and ships bound outward from Amst must sayle round the islands of the Texell before they get to sea and may by cross winds be kept 10 or 12 in that gulf called the South Sea so a ship may make 3 returns from Rotterdam to Eng before one may gett clear of the texell, for which reasons our Eng Merchants finding it more to their advantage, send their effects consigned to men at Roter who send them up their canals to Amsterdam.

Child’s description is especially partial to the maritime environment of Dutch towns and his interest extended beyond urban geography to the wider architectural and material culture of the sites. At many points, the journal describes the construction of Dutch boats and ferries, their design and their holding capacity.[28] Another one of Child’s specific interests is in monuments and sculptures and their accompanying inscriptions in Latin as well as the design of various coats of arms. For example, in his description of the ‘…mausolee erected to perpetuate the memory of Willm Henry Prince of Orange the father of this powerfull and flourishing Republik’, he not only details the design of the monument, its iconography, the materials (marble, iron, brass) but also the arms of the families of the house of Nassau.[29]

Francis the elder’s keen eye for antiquities and scientific curiosities complemented his penchant for detail. He made a special visit to a Monsieur La Faille (a notable in the court of Henry VIII) to view his “curious collection of Modern medals” and wrote about a Mons D’ Hequett’s chamber of rarities, which was ‘worth any one’s asking the favour to see them.’[30] Francis Child’s most important visit was to the microbiologist and lensmaker Antonie van Leeuwenhoeck (1632-1723) ‘…so much esteemed amongst the virtuosi and a fellow of our Royal Society lives here and willing to show any strangers recommended to him as curious those microscopes he first invented and has since brought to perfection …make it appear they magnify 1000000 times.’ Francis was evidently excited to get a first hand experience of using one of Leeuwenhoeck’s microscopes. He wrote that Leeuwenhoeck ‘… show’d us by them, the testicles, & eggs of lice, the eggs of oisters & several other dissections of the most minute insects, which any one may be better informed of who reads his Areana Naturo Detecta.’[31]

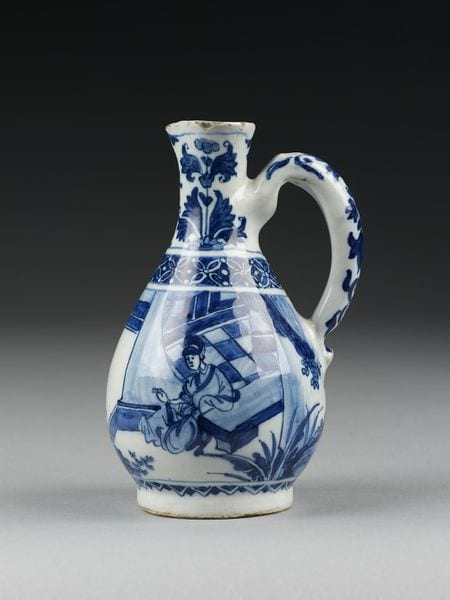

Figure 5: Delft Ceramic Jug in the style of Chinese blue and white porcelain. 1691-1700 (made). Made at the factory “De Metaale Pot”, Delft, under the ownership of Lambertus Van Eenhoorn. LVE mark for 1691-1724. V&A Museum, C.2360-1910.

Francis Child’s impressions provide a vivid account of the décor and furnishings of grand mansions in the region and of the display of ‘exotic’ objects from the Americas and Asia. In Delft, Child made a special mention of the quality of porcelain manufactured in the town:

…They brew very good beer, but are perticularly famous for their Porcellane or earthern ware, which they paint better then the Chinese, make more large, and as beautifull everyway, could they but make their small ware transparent in which the Chinese have the advantage of them.[32]

Francis Child’s observation about the unique transparency of Chinese porcelain compared to Delft earthenware was a very astute one. Tin-glazed pottery had been produced in Holland since the first quarter of the sixteenth century and Delft had emerged as one of the main centers for its production in the seventeenth century. With the rise in import of Chinese porcelain by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) after 1602, the fashion for blue and white porcelain put traditional Delft ceramic wares into competition with their exotic counterparts. As a result, from the first quarter of the seventeenth century, Delft potters had begun to imitate the transparent finish of Chinese blue and white porcelain ware by using Chinese style decorations in cobalt blue over a white-tin glazed background (Figure 5).[33]

In his journal, Child’s fascination with Asian decorative art continues as he lingers on the description of grand interiors of palaces and mansions. His longest description is of King’s house in the Bosch:

The left side of the room is one great picture of this King’s grandfather, drawn in a triumphall chariot by white horses, attend by many figures. This piece is all of Rubens, and the rest of the room is painted by him and other Masters…several of the other rooms are well furnisht and have pieces of Van Dyke in them. Here is a curious closet made of the best sort of Indian Screens, the floor inlaid, the ceiling of Lookinglasse with Gold cyphers on it. This closet is very full of fine China, which because place’d by late Queen, the King has ordered shall not be removed. Belonging to this house, is a large garden with terrass walk, and a labirinth pretty to behold, but very different to get out of.[34]

Child seems to be particularly interested in the interior decorations within palatial homes and in the display of artistic virtuosity, whether in European master paintings or Asian decorative art. In Honselersdijk, south of Hague, Francis Child went on to describe the interiors of the palace apartments: ‘the apartments are well furnished and have in them good pictures of several great Masters…Here are closetts of choice pieces, especially one very large of Japan [lacquer], the ceiling of lookinglasse with flowers painted on it and over the chimney was fine China nearly placed by the late Queen’.[35]

Francis Child the elder’s journal conveys how his travel to the Netherlands played a significant part in shaping his aesthetic sensibilities, at a time when he was about to begin his significant engagement with the East India Company. His many visits to country mansions and palaces highlight his specialist interest in Asian objects and furnishings – painted screens, porcelain, and lacquerware to name only a few exotic commodities associated with the EIC. Child is keenly aware of decorative art from Asia, its status as a rarefied privilege, and the all-important channels of maritime trade that brought decorative objects from Asia into Europe.

Though not much is known about decorative objects acquired by Child in the Netherlands, his visit resulted in the purchase of over sixty paintings by great masters, which he brought along with him to London. At the time of the visit to the Netherlands, Francis Child resided in his London home Hollybush House, overlooking Parson’s Green in Fulham, Middlesex, which he had inherited from Robert Blanchard’s wife in 1686.[36] His son, Robert purchased 42 Lincoln’s Inn Fields (now the Royal College of Surgeons) in1702 and Francis the elder lived there from 1704 thus this entry was made into the journal a few years later.[37]

The journal carries a list of these paintings by great Masters under the heading A catalogue of my pictures in my house in Lincoln Inn’s Fields taken March 9, 1706 and of my drawings in frames with glass. There are sixty-one paintings in all (with six unnumbered additions) and also a price list specifying the amount paid for them. The total summarized at the end of the list is £4850, a sum in the millions today.

The presence of another hand list of pictures, which are sorted by their physical placement in 42, Lincoln’s Inn Fields provides a deeper insight into the Child family’s status in London’s metropolitan polite society. This second list details the spaces occupied by the paintings in the house. For example, a ceiling piece by Reubens and a painting of King Charles on Horseback by Van Dyck is listed under the heading ‘Staircase.’ Paintings by Salvator Rosa, Claude Lorraine, Guido and Caracci among others are listed as on display in the Dining room.

From Father to Son: Robert Child (1674-1721) and St Luke’s Club

While there is every possibility Francis the elder wrote this second list, the presence in it of a portrait of his son Robert raises the alternative possibility that the list was written by Robert Child. A clue is provided by the paintings listed as belonging to the ‘First Parlour’ – listing a portrait of ‘Sr Robert Child’ by the Swedish painter Michael Dahl (1656/1659–1743). The association between the two individuals forms an important context for thinking about Robert’s own interest in the artistic culture of the period. Michael Dahl, the portrait painter, was part of a group about twelve members forming the Society of the Virtuosi of St Luke (active c.1689–1743), also known as St Luke’s Club or Vandyke’s Club, which comprised of artists and gentlemen who met frequently to engage in conversations and debate on matters of taste.[38] The club’s name related to the annual celebration of the festival of St Luke, the patron saint of painters and it was one the prominent forerunners to specialist academies such as the Royal Academy of Art, which was formed only in 1760. The Society’s records show that in the first decade of its revival in 1689, Robert Child was one of an exclusive group of twenty members of St Luke’s Club along with Christopher Wren the younger (1632-1723), the surgeon and anatomist William Cowper (1666-1709), and the painter Hugh Howard (1675-1737).[39] Furthermore, the title of Dahl’s portrait of Robert Child in the Lincoln’s Inn Fields House suggests that it was painted after Robert was knighted in 1714 – in the year after Francis the elder’s death. This is a significant but often overlooked fact, since it raises the possibility that Robert Child added this second list of paintings in his father’s journal. Moreover, it is possible that the list functioned as an inventory of the paintings in Lincoln’s Inn Fields and was entered into the journal around the time of the Child family’s relocation to Osterley Park after 1713. From this period onwards Robert took on the full responsibility of refurbishing Osterley as the new Child family home.

Sir Robert Child (1674-1721)

Francis’s eldest son Robert became and Member of Parliament in 1710.He was elected as a Director of the EIC in 1710 and was repeatedly elected in this post with hardly a break until 1720. He was a hard working Director, attending nearly all the weekly meetings of the Court. Like his father he served on the more important EIC committees: Accompts (Accounts) & Warehouses Treasury and Bullion in 1712 and later Correspondence and Treasury in 1720.[40] In the course of the first session he was identified by Abel Boyer as one of the ‘High Church’ candidates standing at the elections for the East India Company.

Figure 6: East India Company Sale Room at Leadenhall Street, 1808 Rowlandson, Thomas et. al. Aquatint, coloured, 266 mm x 315 mm, National Maritime Museum, PAD1361.Three years after his appointment to the Court of EIC (1713) Robert took over the Child & Co. bank and became an Alderman of the City of London.[41] He was not a Director of EIC during this year but led a shareholder petition, successfully arguing for better governance of the company:

Mr Alderman Child with several of the Adventurers attending the court delivered a request which was read, subscribed by many of the Adventurers, wherein the Court was desired to use their endeavours to obtain an alteration of the Company’s charter, so as to have a Governor and Deputy Governor, and to increase the Qualifications of all future Directors. And he did in the name of himself and several others of the Adventurers as well present as absent, desire the Court would take the same into consideration and then withdrew.[42]

A special meeting of the General Court was called. Result nemine contradicente (no-one dissented) and it was referred back to the Court of Directors for action.[43]

Sir Robert Child: From Director to Chairman

In April 1714 Robert was elected Director and deputy Chairman. In the same year he was also knighted by King George I. By the following April, apparently after a struggle with the Bank of England interest headed by (Sir ) Gilbert Heathcote,he was elected Chairman.[44] Lord Treasurer Oxford (Robert Harley) ‘took particular notice’ of Child when a delegation from the company attended the minister as can be seen from the Court Minutes:

Sir Robert Child acquainted the Court that several of the Directors with himself went up to the Treasury with the Companyes memorial, touching the deficiencies on the Fund. The Chairman attended the Rt Hon Lords Commissioners of His Majesties Treasury who promised to [take] most utmost care of the Funds…..Several of the Directors acquainting the Court that the Chairman had addressed himself to their lordships in a very particular and obliging manner, and the Court being informed of the substance of what was spoken they unanimously returned the Chairman their hearty thanks for the same.[45]

His status is underlined in Daniel Defoe’s anonymously authored pamphlet published the same year, the Secret History of the White Staff (1714), which includes a reference to ‘Sir R. Ch.’ as one of the ‘jobbers and monied men’ who had grown rich at the nation’s expense.[46] The following April he was elected Director of EIC and Deputy Chairman, and went on to be Elected Director and Chairman for the year April 1715-1716. His influence with the Treasury is apparent:

On 10 Oct 1715, ‘The Chairman attended the Rt Hon Lords Commissioners of His Majesties Treasury to congratulate their Lordships that the Directors were received in a very obliging manner by their Lordships who promised to [take] most utmost care of the Funds. And that as the Company should have free access to them at all times, so their Lordships would give them what assistance was in their power in any difficulty relating to the Companyes affairs.’[47]

He continued to play a part in the day to day trading of the company,

On 7 Jan 1715, ‘The Court being informed that the Rt Hon The Lord Commissioners of his Majesties Treasury have earnestly recommended to the Company to take off a quantity of Tin. That it be referred to Sir Robert Child, Sir Robert Nightingale, and Mr Gould, or any two of them to consider what quantity of Tin, and at what price it is proper to send to the East Indies.’[48]

During his time as Director EIC’s trade with China had increased to the point that in 1722 the Company set up its Council of China; the Spitalfields riots led to a ban on imported cotton textiles; the Treaty of Utrecht was signed and the Company had to help the government pick up the financial pieces following the demise of the South Sea Company. After an unsuccessful bid to the Government to obtain a better deal for this the following January the Directors agreed that ‘Being deeply sensible of the Nation’s present unhappy circumstances are very willing to contribute their utmost towards retrieving then and repairing and supporting the National Credit over their own particular detriment’.[49]

Francis Child II (1684-1740)

Sir Robert died in 1721 and his place in Child & Co. was taken by his younger brother Francis Child II. The business continued to thrive, and in 1739 Child greatly expanded its premises in Fleet St. The banking business had moved on and at this time there were very few loans of the traditional gold-smith type, on the security of silver or gold plate and precious stones. There were important advances made to City dealers secured, upon parcels of stock and heavy investments in East India securities.[50] A partner in the Bank, John Morse, left £10,000 each to Francis and Samuel Child in his will of 1736.[51]

The younger Francis retained his involvement with the Goldsmith Company, serving as its prime warden in 1723-4.Like his father Francis Child was elected an Alderman (in 1721), and held the position until his death in 1740, serving as Sheriff of London (1722–3), as Lord Mayor (1731–2) and as an MP from 1722 -1740. For the first five years he was MP for the City of London, and, like his father, served as president of Christ’s Hospital. He rented out most of his large property portfolio but seems to have been the first member of the family to carry out major alterations at Osterley, probably including laying out the formal gardens.[52]

Francis Child II was elected to the EIC Court as Director in April 1721 and, like his father and brother before him, was appointed to the major Committees, those covering Accounts, Warehouses, and Private Trade. He served as Director with until 1732, apart from an obligatory gap every 4th year.[53]He also attended EIC Court meetings regularly and was one of the Directors who agreed to attend the Company auctions every week.

1722 saw the establishment of the Company’s Council of China, in recognition of the growth of trade with that country. Another extract from the Court minutes also demonstrates that in January of that year, Francis Child had a particular role to play

Mr Dubois acquainted the Court that a parcel of Diamonds had been seized by an officer of the Customs upon one of the Mates late belonging to the Chandos and upon enquiry into the fact by the Commissioners of Customs then relinquish the seizure and then directed the Diamonds to be sent to this house in order to ascertain the duty thereon but no Bill of lading appearing desired that the Court Direction before the delivery. [The Court] ordered that the said Diamonds be delivered to Alderman Child he paying the usual duty and giving receipts for same.[54]

He was knighted on 28 September 1732.

Samuel Child (1693-1752)

After Francis the younger, there does not seem to be any member of the Child family serving as a Director of EIC—although, as we will see, this did not sever the family’s deep links with the Company. The youngest son of Sir Francis the Elder, Samuel Child, took on responsibility as head of the family banking firm. He held a large number of EIC stocks and in his will left his wife £45,000 of EIC stock and £3000 to his son Francis.[55] Apart from these stocks his only interest in the company seems to have been as co-owner of the EIC chartered ship the Northampton, which was unfortunately lost in a violent storm in 1744 on its way back from a voyage to China and India.

Samuel was the only son of Sir Francis Child the elder to have children, and so his two sons Francis III and Robert inherited the Child family fortune, which had been accumulated since Sir Francis was apprenticed in 1664. Both were educated at Oxford, were partners in Child and Co and were responsible for transforming Osterley into the house it is today.

On 31 December 1760 Samuel’s son Francis held nearly £33,000 worth of East India stock (according to ledgers A-G), and left his fiancée £50,000 when he died in 1763, days before his impending marriage, the bulk of his estate going to his brother Robert.

Robert and Sarah Child

Robert married Sarah Jodrell (1741-93) of Ankerwyke in Buckinghamshire in 1763. Robert and Sarah are credited with working with Robert Adam to change Osterley House into the Neo-classical house it is still today. Link to Osterley objects Although Robert does not seem to have been involved with EIC, other than as a shareholder, the Jodrell family had longstanding links to the Company. Sarah’s grandparents were 1st cousins and both their families had an EIC related heritage. One of Sarah’s great-grandfathers Richard Craddock had been an EIC factor in India and Persia in the seventeenth century. Another great grandfather was Daniel Sheldon, who was a factor for the East India Company in India. In 1659 he wrote to another factor for the company at Bandel (outside Calcutta in Bengal) urgently requesting a sample of tea to send home to his uncle Dr Gilbert Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury. He wrote:

I must desire you to procure the chaw, if possible. I care not what it cost. ‘Tis for a good uncle of mine, Dr Sheldon, whome somebody hath perswaded to study the divinity of that herbe, leafe, or what else it is, and I am soe obliged to satisfy his curiosity that I could willingly undertake a viage to Japan or China to doe it.

Later he wrote, ‘for God’s sake, good or badd, buy the chaw if it is to be sold. Pray favour me likewise with advise what ‘tis good for, and how it is to be used…’ [56]

Over the course of his career in the EIC, Daniel Sheldon’s personal gifts to his relatives and friends also included objects that were rooted in the material history of Indian court culture. The Gentleman’s Magazine of Oct 1768 describes a chess set that Daniel Sheldon, an Indian Merchant, gave to Dr Hyde, Librarian of the Bodleian Library and a Professor of Hebrew and Arabic in 1694. It was made of solid ivory, varnished and interspersed with gold; the pieces for one side are white, for the other green. Dr Hyde described the set as:

The most precious and at the same time the most adorned and ancient of this sort of board is one which I possess, brought from India, the gift of my magnificent and ever-to-be-honoured friend, Daniel Sheldon, Esquire, a merchant trading to the East Indies.[57]

Robert Child died 28 July 1782, aged 43. The Gentleman’s Magazine’s obituary of him stated: ‘He has died worth £15,000 per annum in landed property, exclusive of his seat at Osterley Park, which is deemed the most superb and elegant thing of its kind in England. His share of the profits in the banking business has never been estimated at less, for some years, than £30,000 per annum.’ He was in addition a considerable holder of Government stock.[58]

But it seems that the Child’s interest in the EIC, which had always been commercial, passed to those partners who had an active role in running the bank. Thomas Devon, a partner in 1752 was a significant supporter and backer of Lawrence Sullivan in the highly charged fight between him and Robert Clive over control of the Company.[59]

Return to Osterley Case Study menu / Next

[1] Numerous references in Court Minutes of the EIC, B51-3, B56-62, British Library.

[2] The National Archives HCA 26/8/107 & HCA 26/4/86.

[3] “Lord mayors of the city of London from 1189” City of London Records, [http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/about-the-city/who-we-are/key-members/the-lord-mayor-of-the-city-of-london/Documents/list-of-lord-mayors-nov-2012.pdf accessed July, 2013.]

[4]British Library IOR/ B/96, p. 327.

[5] Chapman, “Sans Coronet,” pp. 7-8.

[6] Philip Beresford and William D. Rubinstein The Richest of the Rich Wealthiest 250 people since 1066 (Harriman House Publishing, 2007).

[7] Edgar R. Samuel, “Sir Francis Child’s Jewellery Business,” The Three Banks Review, (March 1977): 43-54.

[8]Philip Winterbottom, ‘Child, Sir Francis, the elder (1641/2–1713)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5286, accessed 22 July 2013].

[9]William Chaffers Reeves and Turner, Gilda aurifabrorum (1899), p. 74.Reprint published by BiblioBazaar, 2008. E-copy of original available from General Books LLC, 2012.

[10] Winterbottom, ‘Child, Sir Francis, the elder (1641/2–1713)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004); online edn, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5286, accessed 22 July 2013].

[11] LMA, CLC/521/MS16864.

[12] The history of England: during the reigns of King William and Queen Mary …By Mr. Oldmixon (John) Printed for T. Cox, 1735.

[13]Grasby, Richard, The English Gentleman in Trade: The Life and Work of Sir Dudley North 1641-1691 (Clarenden Press 1994), p. 68.

[14] John S Forbes, Hallmark: a history of the London Assay Office (1999), p. 349.

[15] Quinn has observed that during the political crisis of 1688 resulting in the leaving of James II of England, Child lent money to a number of well-connected people. He goes on to mention that “In a rare entry, Child even lent three thousand pounds directly to the East India Company in February of 1688”. Stephen Quinn, “Tallies or Reserves? Sir Francis Child’s Balance Between Capital Reserves and Extending Credit to the Crown, 1685-1695,” Business and Economic History, 23 No. 1, (Fall 1994), pp. 39-51, 43. For a discussion of the nature of credit and its ethical and moral underpinnings, see Margot C. Finn. The Character of Credit: Personal Debt in English Culture, 1740-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[16] Edgar R. Samuel, “Sir Francis Child’s Jewellery Business,” The Three Banks Review, (March 1977): 43-54. Also see, Raphaelle Schwarzberg, “Becoming a London Goldsmith in the Seventeenth Century: Social Capital and Mobility of Apprentices and Masters of the Guild” Working Papers No. 141/10, Department of Economic History, London School of Economics, June 2010. For a larger discussion of the role of precious metals in supporting EIC trade see, Bruce P. Lenman, “The East India Company and the trade in non-metallic precious materials from Sir Thomas Roe to Diamon Pitt” Huw Bowen, M. Lincoln, N. Rigby eds. The Worlds of the East India Company (Boydell Press, 2002), 97-110.

[17] Royal Bank of Scotland Archive, quoted in Philip Winterbottom, “Child, Sir Francis the Elder” in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. As cited by Lissa Chapman, “Sans Coronet”, 17.

[18]Lissa Chapman, “Sans Coronet”, 17.

[19]Letters illustrative of the reign of William III from 1696 to 1708 addressed to the Duke of Shrewsbury by James Vernon, ed. GPR James (1841), vol. 2, 186; Chapman, 17.

[20]Court Minutes of the EIC April 1699- April 1702 B 43.

[21] Court Minutes of the EIC April 1699- April 1702, BL/IOR B 43, 5 July 1699.

[22] David Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, S. Handley, Eds. The House of Commons, 1690-1715 (History of Parliament Trust, 2002).

[23] Court Minutes of the EIC, Volume B50a, 1706-8.

[24] Court Minutes of the EIC 1712-13 B 52, 4 May 1711.

[25] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/1128/177 and 178.

[26] ACC/1128/177, p. 13.

[27] On June 2, 1697. ACC/1128/177, p. 3.

[28] ‘From Rotterdam there goes every hour of the day a trechtschuit to Delfe…’ He then proceeds to describe the passage boat in detail. He describes the construction of the boat, its 10 ft high mast, capacity to hold 60 passengers, and its horse drawn mechanism. ACC/1128/177, p. 5.

[29] ACC/1128/177, p. 6.

[30] ACC/1128/177, p. 7.

[31] ACC/1128/177, p. 7.

[32] ACC/1128/177, p. 6.

[33] This information is summarized from C. H. de Jonge Delft ceramics Trans. Marie-Christine Hellin, (New York, Praeger, 1970).

[34] ACC/1128/177, p. 14.

[35] ACC/1128/178.

[36] Winterbottom, “Child, Sir Francis the Elder” in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), online edn, 2006. Also, C. J. Feret, Fulham old and new being an exhaustive history of the ancient parish of Fulham, Vol. 2 (London, 1900).

[37] Winterbottom, “Child, Sir Francis the Elder” (2004), online edn, 2006.

[38] Martin Myrone, ‘Society of the Virtuosi of St Luke (act. c.1689–1743)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2013. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/theme/96316, accessed 23 July 2013]

[39] Martin Myrone, ‘Society of the Virtuosi of St Luke (act. c.1689–1743)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2013. Also, Bignamini, ‘George Vertue, art historian, and art institutions in London, 1689–1768’, Walpole Society, 54 (1988), 1–148.

[40]Court Minutes of the EIC, BL/IOR B 51-53, 1710-12; B56, 1720-22, p. 8.

[41] The Aldermen of the City of London, Henry III- 190, http://www.british history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=67248] Feb 2013.

[42] Court Minutes of the EIC, BL/IOR B52, 9 December 1713.

[43] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B 51 -53, 1710 – 1712.

[44] BL/IOR B 51 -53, 1710 – 1712.

[45] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B53, 1714-1716, p. 458.

[46]Secret History of White Staff, pt. 3, p. 38; Beaven, 123; PCC 177 Buckingham (cited by www. History of Parliament online- http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1690-1715/member/child-robert-1674-1721).

[47] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B53, 1714-1716, p. 458.

[48] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B53, 1714-1716, p. 247.

[49] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B56, 1720-22, 4 Jan 1720. Court Minutes date the year April to April so in reality this was Jan 1721.

[50]D. M. Joslin, “London Private Bankers, 1720-1785” The Economic History Review, New Series, 7, No. 2 (1954): 167-186.

[51]FG Hilton Price, The Marygold by Temple Bar (London: privately published by Bernard Quaritch, 1902), p. 31.

[52] Child & Co. archives, Royal Bank of Scotland, Mss, unpublished handout.

[53] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR/B 59, 1726-28; B60-B62.

[54] Court Minutes of the EIC BL/IOR B57, 9 January 1722.

[55]Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol. 23-24 (1950), p.180

[56] William Harrison Ukers, All About Tea (The Tea and Coffee trade journal company, 1935), p. 40.

[57]Robert Blair Swinton Chess for Beginners and the Beginnings of Chess by (T. Fisher Unwin, 1891), p.175.

[58] The Gentleman’s Magazine (1782), p. 406; As cited in Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier, ed. House of Commons 1754-1790 (Boydell & Brewer, 1985), p. 212.

[59] “Mr Walsh in a letter to Lord Clive of 14th of Feb 1765 after telling him of Mr Sulivan’s having split a number of votes and of Mr Divon (Thomas Devon, a partner of Child’s house) having split 30,000l.” Major General Sir John Malcolm, The life of Robert, Lord Clive: collected from the family papers communicated by the Earl of Powis Vol. 2 (London, 1836), p. 212.