Familial belonging

Familial belonging

Maintaining a shared identity across imperial space was an important but endless task for the Amhersts. Research by Kate Teltscher, Elizabeth Vibert, Margot Finn and Sarah Pearsall has revealed that imperial families keenly felt the distances placed between different members and developed a range of strategies to traverse spaces of absence.[1] Correspondence and gift-giving, for instance, went some way to mediating a sense of family belonging over time and space. William Pitt Amherst’s daughter Sarah Elizabeth was an active correspondent, who sent sketches as well as letters while in India between 1823 and 1828. In 1824, for example, she wrote to her brother Frederick (1807-29) – who had remained in England – and included a detailed set of five sketches showing their primary residence Government House from several different angles in the hope that he would ‘better to understand the local situation of Government House’. These sketches were accompanied by written notes, which further described details represented in the drawings. Sarah Elizabeth asked that Frederick not keep the sketches to himself, but rather share them with their half-sisters Maria and Harriet to show ‘how the flower garden is laid out’.[2] Sarah Elizabeth thus encouraged her brother to respond to the sketches as he would do letters, as a form of communication that could be shared and read communally.[3]

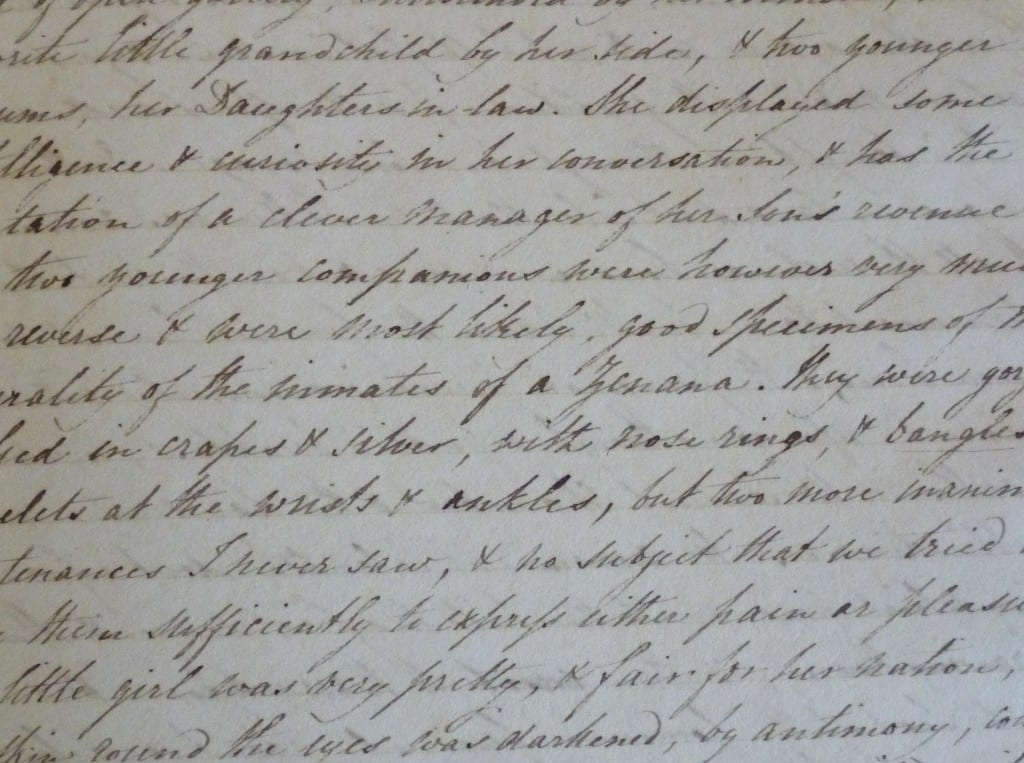

The Amherst family also developed other techniques through which they could create and recreate a sense of the familial across distance. They employed journals to recount experiences and events, which other family members then read at a later point. For instance, on her younger brother Frederick’s return from Italy in 1829, Sarah Elizabeth recalls how she ‘read with the greatest pleasure & admiration his journal in Italy – it was so neatly kept & his account of every thing he saw so good & clear’.[4] While scholars have long understood letter reading as a shared and communal practice, less attention has been given to similar practices of journal reading, but this remained an important strategy for the Amhersts and others, such as the Clives.[5] When in India between 1823 and 1828, for example, Sarah Amherst and her daughter Sarah Elizabeth both used journals to record their journeys to and experiences of India. Sarah wrote a total of seven journals beginning in 1823 with their journey to India and ending with their return to England in 1828, while her daughter Sarah Elizabeth wrote four journals covering the years 1820 to 1842. Sarah Elizabeth’s reading of Frederick’s journal suggests that her own (and her mother’s) journals were produced with a particular audience in mind and actively participated in reaffirming a sense of familial belonging when read by others on their return from India. Significantly, through the emphasis placed on reading journals once returned, these practices suggest at the importance the Amherst family placed on reconstituting a sense of familial belonging once physically present and returned home.

[1] Kate Teltscher, ‘The sentimental ambassador: the letters of George Bogel from Bengal, Bhutan and Tibet, 1770-1781’, in Rebecca Earle (ed.), Epistolary Selves: letters and letter-writers, 1600-1945 (Aldershot, Brookfield, Singapore and Sydney: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 79-94; Elizabeth Vibert, ‘Writing “Home”: Sibling Intimacy and Mobility in a Scottish Colonial Memoir’, in Tony Ballantyne and Antoinette Burton (eds), Moving Subjects: Gender, Mobility and Intimacy in an Age of Global Empire (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009), pp. 67-88; Margot Finn, ‘Colonial Gifts: Family Politics and the Exchange of Goods in British India, c. 1780-1820′, Modern Asian Studies, 40, 1 (February 2006), pp. 203-232; Sarah M. S. Pearsall, Atlantic Families: Lives and Letters in the Later Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 5.

[2] British Library, Prints and Drawings Collection, ‘Drawings of Government House, Calcutta’, August 1824, WD4131.

[3] For more on letter reading as a shared practice see Rebecca Earle, ‘Introduction: letters, writers and the historian’, in Rebecca Earle (ed.), Epistolary Selves: Letters and Letter-Writers, 1600-1945 (Aldershot and Brookfield: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 1-14.

[4] Claydon House Trust, Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time’, 10/1082/3.

[5]Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time’, 10/1082/3.