A Shared Project

Once returned to England in 1828, the Amhersts initiated other projects to ensure that a sense of familial identity was quickly restored. As well as shared trips and journeys the Amhersts also began refashioning their country house, Montreal Park in Kent. At one level, refashioning can simply be understood as an attempt to render in material terms the new wealth and status they had acquired in India. Certainly on making the decision to go to India in the winter of 1822-23, the economic benefits that might accrue from service featured highly in their discussions. They asked their acquaintances and friends for advice on whether the post would be economically and emotionally worthwhile and their advisers suggested that although the emotional costs might be high, the economic gains made the move worthwhile. More particularly, acquaintances suggested that the Indian post would ultimately allow their male children to prosper – ‘only consider what an advantage a few score thousand pounds will be in setting up these Lads’.[1] In addition to wealth, moreover, while in India, Amherst also managed to acquire status. In 1826 William Pitt had been created 1st Earl Amherst of Arracan and Viscount Holmesdale, honours which moved the family up a rank within in the peerage. Yet, despite having reasons to embark on the materialization of power and wealth through house building, the new house created by the Amhersts remained relatively modest. Significantly, in the 1970s, the 5th Earl Amherst simply described Montreal as ‘a comfortable Georgian house’ (see figure 1).[2] It is important then to look beyond the architectural outcomes of building and to instead focus upon the building process itself to understand why the Amhersts embarked on their renovation of Montreal in the late 1820s. In reconstructing their country house, I argue they sought primarily to reconstitute a family identity and sense of belonging, which had been dispersed by imperial distance.

In 1829 the Amhersts commissioned the architect Mr Atkinson to draw up plans for a substantial extension to accommodate a billiard room and new bedrooms and dressing rooms for Lord and Lady Amherst.[3] Notwithstanding their employment of Atkinson, the Amhersts actively involved themselves with the design process and conceived it as a collaborative act. In her journal, William Pitt Amherst’s daughter Sarah Elizabeth, described how before they hired Atkinson, they spent much time working with a scale model of the house and its proposed extension. She described how they ‘had a model of it in wood, with a moveable additional form, to be placed where one chose, but on every side it looked like an excrescence & deformity’.[4] The Amhersts took the unusual step of providing themselves with specialized tools through which they could consider different solutions to the problem of creating an extension at Montreal Park. The construction of a scale model of the house and the proposed extension suggest the high levels of time and effort they invested in the building process.

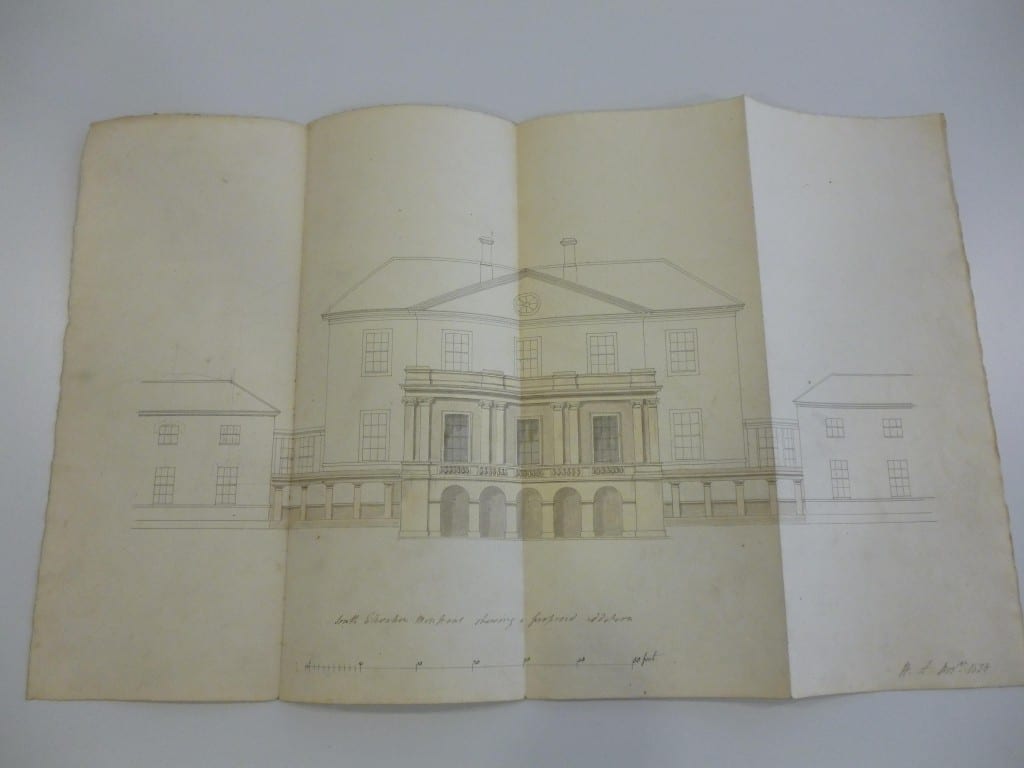

Figure 2. ‘South Elevation Montreal showing a proposed addition’ (November 1828). Courtesy of Kent Library and History Centre

Moving the model into different places, the family’s first solution to the problem of an acceptable extension was to build a two-storey section in front of the house, which could be connected by an arcade to the wings at either side of it (see figure 2 above).[5] Atkinson, however, soon drew the family’s attention to the difficulty of creating an adequate chimney system and began to introduce the alternative idea of extending to the east of the house. He suggested that a substantial addition, which included both extra service rooms on the basement floor and an impressive dining room on the ground floor, could be built on the east side of the house (see figure 3 below). Such a substantial extension, it was argued, would create enough space within the central building of the house to include a billiard room.[6]

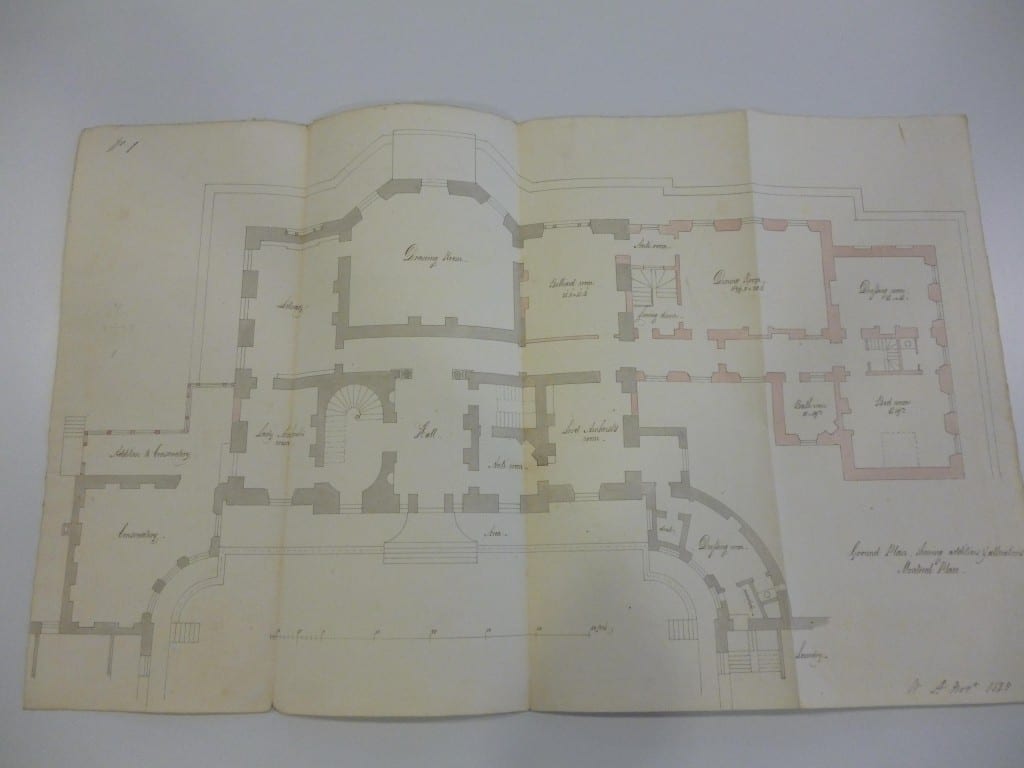

Figure 3. ‘Ground floor plan showing additions and alterations Montreal Place’ (November 1828). Courtesy of Kent Library and History Centre

As Sarah Elizabeth explained in her journal, however, the family greeted Atkinson’s plan with much disapproval because it disturbed the symmetry of the original house. What he was suggesting was an extension that would align the form of the house more closely with contemporary fashions. In the 1790s asymmetric houses began to appear in great numbers. Joseph Bonomi’s (1739-1808) work on Longford Hall in Shropshire and James Wyatt’s (1746-1813) work on Dodington in Gloucestershire in this decade encouraged further asymmetrical houses to emerge in the early years of the 1800s.[7] In the same period the emergence of the Gothic Revival further disrupted the dominance of symmetry, leading to new conceptions of the country house form during the nineteenth century. Although at odds with prevailing trends the Amhersts’ desire for a symmetrical house remained unchanged.

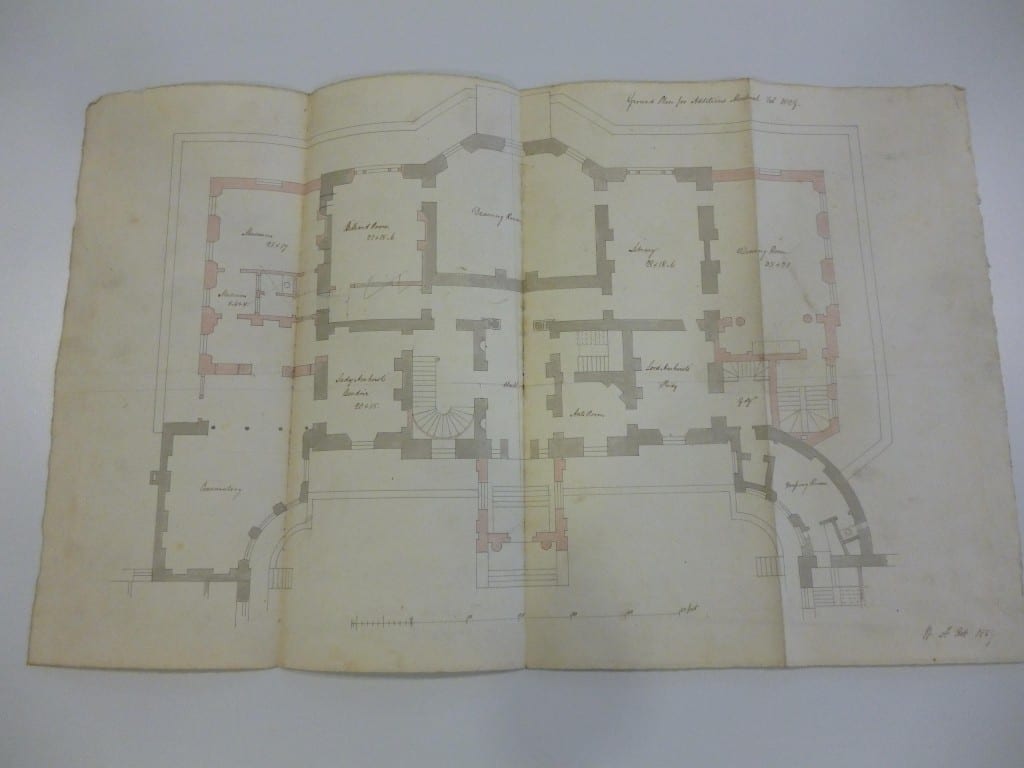

That the Amhersts saw their building project as an endeavor that could benefit from (and provide benefits to) their wider circle becomes clearer at this point in the design process. As described by Sarah Elizabeth, William Pitt actively encouraged other family members and friends, not resident at Montreal Park, to engage in the project. His wife’s daughter by an earlier marriage, Lady Maria Windsor (1790-1855), was called upon and as Sarah Elizabeth notes, she ‘was of great use’. Concerned at Atkinson’s suggestion to build an asymmetrical house, the family ‘pondered a long time over this plan’. At last a certain Mr Addington found a solution – extending the house on both sides. Building two extensions allowed for a less obtrusive addition, retained symmetry and created much space. Sarah Elizabeth describes how her sister ‘immediately reduced the idea to a scale on paper’.[8] After some adjustment, it was this idea that came to be completed at Montreal (see Mr Atkinson’s rendering of the design in figure 4 below).[9]

Figure 4. ‘Ground Plan for Additions Montreal Feb 1829’ (February 1829). Courtesy of Kent Library and History Centre

Significantly, the design work for the extension at Montreal Park was configured as a collaborative endeavour, which utilized the opinions and skills of a range of people. Lady Maria Windsor’s drafting skills – rather than the services of the architect – were particularly useful in allowing the family to quickly move from idea to drawing. Sarah Elizabeth’s description of this act – ‘reduced the idea to a scale on paper’ – suggests that Lady Maria had some experience of drafting and working to scale. Such evidence gestures towards her previous involvement in design, suggesting that she may have been actively involved in other projects. At the same time, the active engagement of daughters in the design process reveals how broad collaborations between family members were enacted to achieve house building schemes.

In early February 1829 the Amherst family left ‘Mr Atkinson the architect in possession of the house to begin operations immediately’ and moved to their London abode.[10] Eight months later they moved back to Montreal and Sarah Elizabeth recalled how ‘every thing was so changed, in consequence of the alterations in the house, & the enclosure of the new garden that we hardly knew the place again’.[11] Despite creating a new space that seemed unrecognizable at first, the process of creating that newness spoke more of consolidation than change. In working together as a family, the Amhersts created a building solution acceptable to all. Montreal Park became an important and meaningful place again due to family members investing time and expertise in its reconstruction. Country house building allowed imperial families to integrate not only with elites, but also (and perhaps more importantly) with each other.

[1] British Library, European Manuscript Collection, ‘Letter to William Pitt Amherst’, 24 November 1822, F140/55.

[2] Jeffrey Amherst, Wandering Abroad: The Autobiography of Jeffrey Amherst (London: Secker & Warburg: 1976), p.19.

[3] Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time, beginning with the year 1820’ (1820-1842), 10/1082/3.

[4] Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time, beginning with the year 1820’ (1820-1842), 10/1082/3.

[5] Kent Library and History Centre, Amherst Papers, Detailed Plans of Alterations at Montreal by Mr. Atkinson (1829-31), U1350 P21.

[6] Amherst Papers, Detailed Plans of Alterations at Montreal by Mr. Atkinson (1829-31), U1350 P21.

[7] Girouard, Life in the English Country House, p. 220.

[8]Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time, beginning with the year 1820’ (1820-1842), 10/1082/3.

[9] Amherst Papers, Detailed Plans of Alterations at Montreal by Mr. Atkinson (1829-31), U1350 P21.

[10] Sarah Hay-Williams Collection, Journals of Sarah Amherst, ‘Notes on the events of my own time, beginning with the year 1820’ (1820-1842), 10/1082/3.

[11] Ibid.