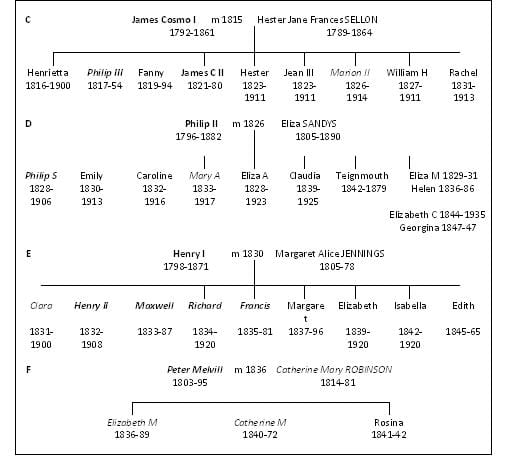

The Third Generation

Philip Melvill (1817-54) (‘Philip III’)

Philip III was the second child and eldest son of JCM I and Hester Melvill. Born on 3 October 1817, he was educated at Harrow, Peterhouse College, Cambridge[1] and the EIC College at Haileybury, graduating from the latter in 1839 as a writer. He arrived in India in February 1840; his first posting was as the agent to the Governor General of the North Western Provinces and by 1854 had risen to be secretary to the Punjabi government. He died of cholera in Lahore on 14 July 1854.[2] On 15 July 1845 he married Emily Jane Hogg (1828-64) in Calcutta;[3] they had two daughters and one son, all born in India. Their son, Philip Lawrence Melvill (1850-79) joined the 97th (Earl of Ulster’s) Regiment in 1870 as a lieutenant,[4] was promoted to captain in 1878[5] but died shortly afterwards at the young age of 29.

James Cosmo Melvill (1821-80) (‘JCM II’)

JCM II was born in London on 8 August 1821. He was educated at Totteridge School and joined the EIC office in Leadenhall Street, aged 16, in 1837. His advancement seems to have owed much to his father. William Foster relates the story of a clerk, who kept being promoted quickly and unexpectedly and without particular merit or influence. He discovered that the clerk below him was the son of the Secretary who had devised the stratagem of promoting the clerk immediately above him to create a vacancy his son could fill.[6] While the Melvills are not mentioned by name, it almost certainly relates to them, given JCM I’s long tenure as Secretary and JCM II’s advancement during that period.

After the transfer of EIC power to the British Crown in 1858, JCM II became Under-Secretary of State for India, a post he held until retirement in 1872. In 1844 he had married Eliza Jane Hardcastle (1822-1904) in Camberwell. After his retirement they went to live in Augusta Road in Folkestone where, judging by the address and the fact that in the 1881 census return they had six servants, they lived in some style. They had four sons, one of whom died in infancy, and five daughters. Their eldest son, another James Cosmo Melvill (1845-1929), was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1874 he married Bertha Dewhurst (1853-1933) of the cotton trading family; he became a director of Geo & R Dewhurst Ltd, East India and China Merchants of London. He was also an acclaimed amateur botanist and zoologist and a fellow of Linnean and Zoological Societies.[7] He wrote on zoological and biological subjects. In his retirement when living at Moele Brace Hall in Shrewsbury he corresponded with family and friends on the origins of the Melvill family; copies of many of his letters are in the British Library.[8] Another son, Arthur (1853-1932) was a clergyman and never married.

Other children of JCM I and Hester

In 1844 the eldest child of JMC I and Hester, Henrietta (1816-1900), married a London solicitor, Richard Beachcroft (1805-1872), the founder of a firm which still carries his name. One of their eight children, Emily Charlotte (1848-1937) is one of my wife’s great grandmothers. Their second eldest daughter was Fanny (1819-1894), who married Rev Henry Holme Westmore (1815-1890) in 1853. The rebuilding of the church at Hutton in 1873 when he was rector is referred to on page 14. Another daughter, Marion (1826-1914) married James Alexander Wedderburn (1825-1854) who was in the Madras Civil Service. Their youngest son, William (1827-1911) was educated at Rugby and Trinity College, Cambridge and qualified as a barrister.[9] He married Elizabeth Lister (1833-1908) in 1862. His final job was as the solicitor for the Inland Revenue and he was knighted in 1888.

Philip Sandys Melvill (1828-1906) (Philip III)

Philip II and Eliza’s eldest son was educated at Rugby and Haileybury, where he received several prizes for Sanskrit and Persian. He arrived in India in 1846 and entered the Bengal Civil Service as an assistant to Sir Henry Lawrence, the Resident at Lahore as well as Agent to the Governor-General for the North West Frontier. Lawrence governed the area with the help of his officers such as Philip, who were known as ‘Henry Lawrence’s Young Men’. Philip became commissioner of a division of the Punjab after an exceptionally short service of thirteen and a half years, then Financial Commissioner of the Punjab before becoming a Judge of the Chief Court in the Punjab. He established a reputation almost unrivalled for an intimate acquaintance with the peoples and their languages. He was then agent to the Governor-General at Baroda until retirement in 1882.[10]

In 1851 he married Eliza Johnstone (1832-1920) in Jullundur. They had two sons and six daughters, some of whom died in infancy in India. Their eldest daughter, Eliza Jane (1853-1942) married Charles Joubert de la Ferté (1846-1835) a colonel in the India Medical Service (‘IMS’) in Jullundur. It was Eliza Jane who, under her married name, wrote the book on the Melvill family referred to on page 2. The de la Ferté’s second son, was Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip Bennet Joubert de la Ferté KCB, CMG, DSO (1887-1965), a senior commander in the Royal Air Force during the 1930s and the Second World War.[11]

At least two more of their daughters married in India, Harriot (1854-1937) to William Warburton (1843-1911), another officer in the IMS, and Helen (1856-96) to Rowland Bateman (1840-1916), a minister of the church. Their eldest son, Philip James Melvill (1858-1935) was educated at Harrow and Sandhurst and returned to India in the Bengal Light Infantry. He married Jessie Ross (1867-1900) in Bushire in what was then Persia and had a long career in the army, including service in the Persian Gulf, until he retired in 1908. During his time in India he had strongly supported the cause of Christian missions with personal support and financial aid and after retirement was involved in the Church Missionary Society in London.

Henry Melvill (1832-1908) (‘Henry II’)

Another Henry, the eldest son of Henry I and Margaret joined the Bengal cavalry, part of the EIC army, in 1849 and retired in 1891 with the rank of Lieutenant-General. He was involved in the mutiny of 1857 and the subsequent fighting. He married Elizabeth Curling (1833-1913) and they had six children, three of them boys who all became army officers, one, yet another Henry (1856-1901), was a staff officer in the Indian army.

Maxwell Melvill (1833-1887)

Maxwell was the second son of Henry I and Margaret. He was educated at Tonbridge and Trinity College Cambridge before going to Haileybury College in 1853 where he was a prize-winner in classics, mathematics, law, and history and political economy.[12] He had a brilliant career in the Bombay Civil service from 1855 to 1887, serving in the Bombay Revenue and Judicial Departments as Assistant Collector and Magistrate, as Assistant Judge at Konkan from 1858 to 1860 and as Assistant Commissioner in Sind from 1862 to 1866. He was admitted to Gray’s Inn in 1866. He then rose through the judiciary, becoming a Judge at the High Court at Bombay in 1869 and then a member of the Council of the Bombay Presidency from 1884 until he died, unmarried, of cholera at Garnish Kurd House, near Poona, in August 1887. He was described by one historian as the ‘…most brilliant member of the Bombay Council’.[13]

Richard Gwatkin Melvill (1834-1920)

Henry I and Margaret’s third son Richard also had a career in India but with a very different outcome to those of his brothers. His early life was conventional; he was one of the last graduates of Haileybury College before it closed and was a prize winner in Persian. He joined the Bengal Civil Service in 1855. He married Gertrude van Cortland (1837-1918) in Umballa in 1858 and they had six children in India, two of whom died in infancy. He worked at various stations during the next fifteen or sixteen years, excluding a three-year furlough from 1867. When he returned in 1870 he was appointed as Deputy Commissioner in Sirsa which is in the Punjab about 150 miles west-north-west from Delhi and about 80 miles from what is now the Pakistan border. His youngest daughter was born in Sirsa in 1871.

However, by 1873, his wife and children were no longer with him and he had some sort of breakdown. The press reported that he had gone native, changing his name to Shaik Abdool Rahman and was known as ‘The Muslim Melvill’.[14] He was described as a ‘pervert’ who had ‘married a Moslem bride. Unfortunately he had a Christian wife to start with’. A letter from a J.M. Machan dated 20 October 1873 confirms the report that on 18 September Richard had made a profession of Mohammadism in the Sirsa town hall before witnesses and married according to the rites of the Mohammeden religion Kureshi Brynon, the daughter of Hydari Brynon, the mistress of the female school in Sirsa.[15] He went on to say that after the marriage Hydari Brynon (aged thirty), her sister aged about sixteen (her husband is an absentee) and her brother took up their residence in the Melvill house.

The same letter says that ‘the girl is said to be 8 years of age’… and the marriage was… ‘designed to cover an intrigue with the mother’. The writer went on to say that Richard invited him to dinner but refused to talk of the marriage saying that he would rather give up the service than his present mode of life and that ‘nothing but superior physical force should tear him away from those who were now drawn to him than anything else in this life’. While this kind of behaviour had been quite usual in the early days of the EIC in India, by the middle of the nineteenth century it was not approved of and was regarded as a form of insanity.[16]

However, the furore did not last too long. Further press cuttings debated whether he should be prosecuted under British or Moslem law and the consensus was that his Moslem marriage was not recognised under western law, while a second marriage was not illegal for Moslems. So he was not prosecuted, but was dismissed from the civil service.

On the 1891 census returns in England his first wife Gertrude is recorded with three of her children in the Isle of Wight and with her status as ‘widow’. In 1901 she still describes herself as a widow but in 1911, which asks for more details about marriages than the previous return, she is boarding with a family and the head records that she is married, has had six children of who three are still living, but does not give her age or the number of years she had been married.

Figure 20. Letter from R.G. Melvill. Melvill Papers, Mss Eur Photo Eur 071, British Library. (c) British Library Board, Photo Eur 071, p. 178.

Meanwhile, in India, Richard had seemingly come to his senses and there is a letter to a newspaper in the BL papers (see figure 23), unfortunately not dated, in which he apologises for his actions and blames the fact that living in Sirsa is enough to drive anybody mad.[17] In 1885 he married, at the age of forty, sixteen year-old Emily Mathias (1869-1942), the daughter of Bishunbenanth Mathias, in a Christian ceremony in Dehra Dun. There is no sign in any documentation that he had divorced Gertrude and the second marriage register records his status as ‘widower’. Richard and Emily had four children and for some years lived in Landour, about twenty miles from Dehra Dun. On the baptism records for his sons Richard’s occupation in 1855 was pleader and in 1888 vakil, an Urdu word for a lawyer or representative. His death was recorded in Dehra Dun in 1920.[18]

Francis Melvill (1835-1881)

Francis, Henry I and Elizabeth’s youngest son entered the Bombay Civil Service in 1855. He married Minnie Hayes (1842-1878) in 1875 in Dublin. Most of his career was spent in Sind, where he rose to Chief Commissioner.

[1] Cambridge Alumni, ibid.

[2] The Times, 22 September 1854.

[3] Allen’s India Mail on FIBIS database, http://search.fibis.org/frontis/bin/, accessed at various times.

[4] London Gazette, 2 September 1870.

[5]Ibid, 28 July 1878.

[6] Foster, East India House, p. 228.

[7] Cambridge Alumni, ibid; Obituary in The Geographical Journal, 56:2 (August 1920), p. 150.

[8] BL Melvill papers, pp. 187-98.

[9] Cambridge Alumni, ibid.

[10] Buckland, Indian Biography, p. 285.

[11] ODNB entry, Edward Chilton, rev. Christina J. M. Goulter.

[12] Cambridge Alumni, ibid.

[13] William Wilson Hunter, Bombay, 1885 to 1890; a Study in Indian Administration (Oxford, 1892), p. 64.

[14] BL Melvill papers, p. 177-86 contain newspaper cuttings and letters on the subject of the Muslim Melvill. Unfortunately the cuttings are not dated nor does it say which newspapers they are from. It is not clear as to which Melvill some of the letters are addressed and the signatures on the letters are not clear.

[15] BL Melvill papers, p. 179-81

[16] See William Dalrymple, White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India (New York and London: Viking, 2003) and Durba Ghosh, Sex and the family in colonial India: the making of empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[17] BL Melvill papers, p. 178.

[18] FIBIS databases, ibid, and BL records of marriages and baptisms.