Purchase

Edward Harrison (1674-1732) inherited Balls Park in Hertfordshire after the death of his father Richard Harrison in 1726.[1] Prior to establishing himself at the estate during the 1720s, Edward had worked in different capacities in the service of the EIC. It is possible that he began his EIC career as purser upon the London in the early 1690s. [See ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, The Exceptional Sale, Christie’s, London, 7 July 2011, p. 60. With many thanks to Sharon Goodman for her original research on the Harrison & Townshend collection, which has greatly enriched this case study.] He certainly went on to captain EIC ships including the Powderham Castle, which sailed to Borneo in the late 1690s and the Kent, which he commanded on voyages to China in 1704-5 and 1706-10.[2] Towards the end of 1710, after completing his final voyage on the Kent, Harrison was appointed Governor of Fort St George, Madras.[3] After completing his tenure as Governor in 1717 Harrison returned to England, where he continued to be involved with the EIC and simultaneously established a career in Parliament. Between 1717 and 1722 he acted as MP for Weymouthand Melcombe Regis before going on to represent Hertford between 1722 and 1726. After moving to Balls Park in 1726, Harrison re-established himself once again within the Company by becoming Deputy Chairman of the Court of Directors in 1728, Chairman in 1729 and Deputy Chairman for a second time in 1731.[4] By the time of his death in 1732 Edward Harrison was deeply embedded in EIC life – he had travelled to places as diverse as Macao and Batavia on Company business, he had led Company operations in Madras and he had worked to govern the Company in London.

Edward Harrison’s EIC career is not visible only through Company records that list orders from the Directors for copper, tea, green ginger, rhubarb, wrought silks, raw silk and china.[5] For Harrison’s experiences of Asia and Eurasian trade were (and are) also made materially manifest through the objects he returned with and the wealth he acquired. Of particular interest here is the ivory furniture he purchased while in India, most likely as Governor of Fort St George between 1711 and 1717. Ivory furniture acts an important signifier of Company connections for historians because it is one of the few Asian goods that can be identified in inventories. Because it was such a distinctive material, men writing up probate records often included the descriptor ‘ivory’ when itemising these objects.[6] In those cases where it is possible to trace a particular piece of ivory furniture to a specific family, distinct craft traditions in different parts of the subcontinent mean that these wares also signal the Indian locations where their owners lived and served. The craft traditions of the two main ivory carving centres in the subcontinent, Vizagapatam near Madras and Murshidabad in western Bengal, employed different techniques during the eighteenth century and thus produced pieces that were visibly distinct. The pieces traced to Edward Harrison, for example, confirm this trend. Produced in Vizagapatam, Edward Harrison’s ivory furniture marks his tenure in the Madras presidency.

Figure 2. Armchair, Ivory, carved, pierced and partly gilded with a caned seat. Murshidabad, ca. 1785. 1075-1882 Victoria & Albert Museum. © Victoria & Albert Museum.

Before the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Mushidabad was an important centre of ivory carving, primarily producing solid ivory pieces of furniture and decorative items. After the Battle and as the British began to administer the diwani in the Bengal region, ivory carvers in Murshidabad increasingly sought to make goods that were desirable to Anglo-Indian consumers. Murshidabad workshops began to produce chairs, candle stands and worktables. Particular skills in solid ivory carving allowed these workshops to produce items with distinctive arms and legs made of turned solid ivory (see figure 2). Amin Jaffer has argued that Murshidabad ‘can now be recognised as most probably the source of most surviving Anglo-Indian solid-ivory furniture.’[7]

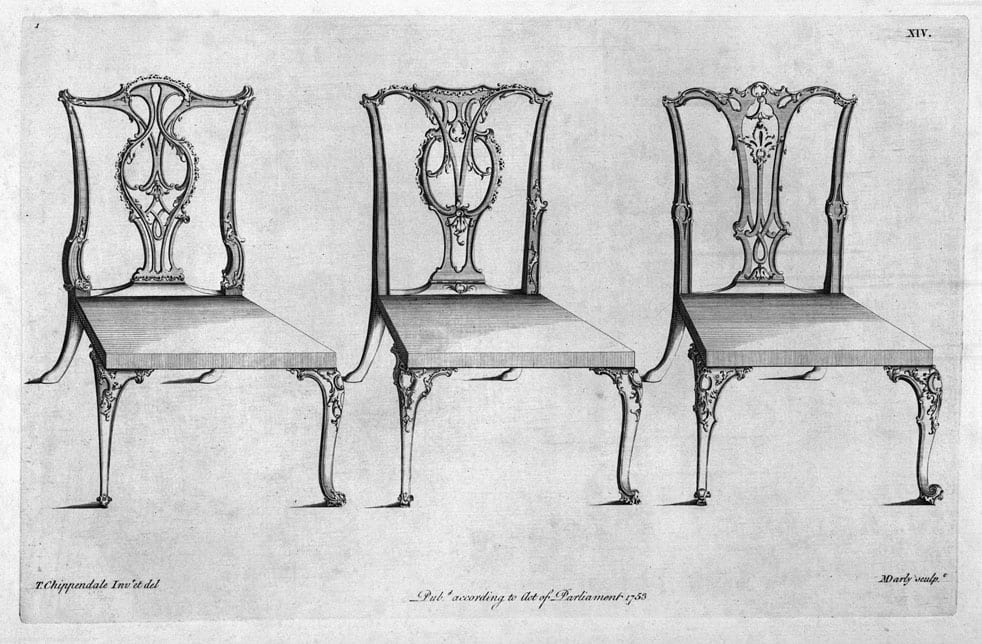

Murshidabad carvers produced furniture that readily conformed to European styles. The circulation of print sources, such as Thomas Chippendale’s The gentleman and cabinet maker’s director (1754) and George Heppelwhite’s The cabinet maker and upholsterer’s guide (1788), containing European designs facilitated this process (see figure 3). Information about European designs was also transmitted to Indian workshops through the arrival of skilled furniture makers from Europe. For example, Jaffer gives particular credit to the presence of Charles Rose, a British furniture maker who was recorded as being in Bengal from 1772 and was registered as an inhabitant in Murshidabad in 1793.[8]

Figure 3. Thomas Chippendale, The gentleman and cabinet maker’s director (1754), p. xiv. See full publication at:http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/DLDecArts.ChippGentCab. Note particularly the central design and the interlocking nature of the back plat, which is replicated in a different form in the ivory armchair in figure 2.

Much further south from Murshidabad, Vizagapatam on the Coromandel Coast was also a key production site for ivory furniture. From the late seventeenth century until the mid eighteenth century, Vizagapatam was especially known for furniture that featured inlaid ivory work (see figure 4). As in Murshidabad, artisans in this area increasingly used their ivory carving skills to produce furniture in Western forms.[9] Between 1760 and 1780, Kamsali caste ivory carvers in Vizagapatam began to use new techniques involving ivory veneer (see figure 5). During this period ivory veneer gradually replaced ivory inlay as the main form of production. It was constructed by attaching a thin layer of ivory, by means of fixatives and rivets, to a wooden carcass. Decorative schemes appeared on these veneers, created by engraving the ivory and then filling the created spaces with black lac to create a monochrome design. While visiting Vizagapatam in 1801 with her mother and sister, Henrietta Clive witnessed the production of these ivory furniture pieces. On 4 April 1801 Henrietta described to her father watching monochrome ivory veneers being manufactured. She described how ‘We have seen the people inlaying the Ivory [with lac]’ and that ‘it appears very simple’. Henrietta observed that ‘they draw the pattern…they intend with a pencil and then cut it out slightly with a small piece of Iron, they afterwards put hot Lac upon it, and when it is dry scrape it off and polish it, the Lac remains in the marks made with the piece of Iron’.[10]

Figure 4. Toilet glass, wood inlaid with ivory. Vizagapatam, 1730-40. 49-1905 Victoria & Albert Museum. © Victoria & Albert Museum.

Figure 5. Toilet glass, sandalwood, veneered with engraved ivory, with silver mounts. Vizagapatam, 1790-1800. IS.31-1975 Victoria & Albert Museum. © Victoria & Albert Museum.

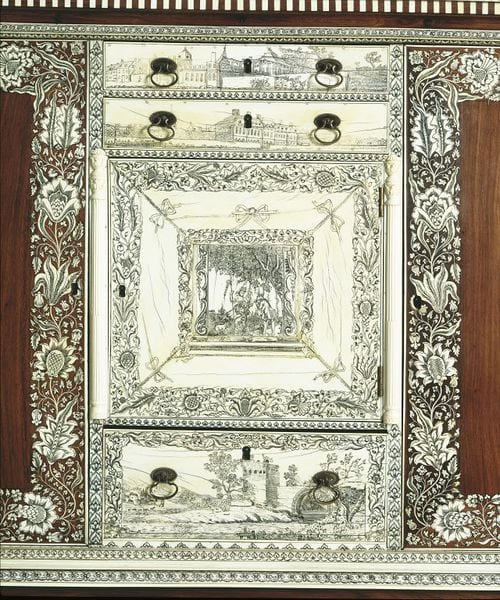

Figure 6. Detail from Cabinet, rosewood, inlaid and partly veneered with ivory, with silver mounts. Vizagapatam, c. 1765. IS.289&A-1951 Victoria & Albert Museum. © Victoria & Albert Museum.

Switching to ivory veneer was an important change in aesthetic terms as it allowed makers a greater degree of flexibility when designing decorative schemes for furniture. Being able to implement a range of decorative schemes became important in the later eighteenth century as carvers began to incorporate increasingly elaborate figurative and architectural scenes into their furniture items (see figure 6). Decorative ivory veneers proved a popular innovation with consumers. Again the circulation of European prints was important to the construction of these wares. Many of the veneer panels included scenes inspired by European prints, which became widely available on the subcontinent in this period.

As Henrietta Clive’s written description of ivory engraving for her father demonstrates, in Britain, people became increasingly curious about the material and the production techniques involved in making ivory furniture, workboxes, chairs and cabinets. Some elite women, such as Margaret, second Duchess of Portland (1715-85) and Mary Delany (1700-88) even took up ivory turning themselves.[11] While a wider interest in ivory had emerged by the mid eighteenth century, in the early decades of the period elite East India Company families, such as the Harrison, were the dominant collectors of ivory furniture pieces.

On Edward Harrison’s death in 1732 appraisers compiled an inventory of movable goods at Balls Park estate. Although Harrison had served as an MP in the later years of his life, in constructing the inventory the unnamed appraiser identified Harrison through his EIC career, as ‘the Honourable Edward Harrison Esq deceased late-Governor of Fort St George at his seat Balls in the County of Hertford’.[12] The inventory demonstrates that the Harrisons were keen collectors of Indian (or Indian-inspired) textiles as well as of ivory furniture. Calico quilts appear in many rooms, including the Nursery, Drawing Rooms, Mrs Harrisons Room, the House Keeper’s Room and Brown Room. The presence of calico in these rooms and not others marks both the rooms and the calicos as of less social importance. In contract, those rooms specifically linked to Edward Harrison and his wife, contained more valuable Indian textiles such as chintz (spelt ‘Chince’ in the inventory).[13] Similarly the ivory objects owned by the Harrisons appear in some of the house’s most public and socially important rooms. ‘The Governors Bed Chamber’, for example, contained ‘a very curious India Book case inlaid with Ivory’, while ‘The Long Galery [sic]’ included twelve ebony ‘China’ chairs inlaid with ivory, as well as two similar elbow chairs and two couches.[14]It is probable that Harrison bequeathed some of his movable household goods to his only child Etheldreda (commonly known as Audrey) (c.1708-1788), as an 1737 inventory for her London home in Grovesnor Street notes that her personal room contained ‘A Desk and book case inlay’d with Ivory’.[15]

In 1723 Etheldreda married Charles Townshend (1700-1764) afterwards third Viscount Townshend. While the relationship between Etheldreda and Charles remained turbulent, the alliance instituted an important link between the East India Company and the Townshend family. Such links were further consolidated when Charles’s brother Augustus captained the East Indiaman Augusta.[16] On his final voyage, destined for China, another Townshend, Roger (d.1759), the fifth son of Etheldreda and Charles, joined Augustus and further consolidated the family’s links to global trade. Before preparations to sail on the Augusta began, Charles and Augustus worriedly wrote numerous letters, ensuring each other that Roger was sufficiently kitted out for the voyage. Augustus advised that around £200 would be required to see Roger set up on ship and during the journey.[17] After setting sail in February 1745, Roger finally returned to Britain in November 1749. He returned without his uncle who had died on board ship and despite the Augusta being captured by the French as it tried to return home.[18]

The difficulties Roger experienced might explain why on returning he was distinctly keen to switch profession, hoping instead to join the army or navy. Charles wanted Roger to remain in the Company, but remarked to his brother that at least a change would mean that the family were no longer dependent on the solicitations of the Court of Directors.[19] While the Townshend family’s growing range of connections to the East India Company is made visible through these professional concerns, Etheldra’s earlier connections to the Company through her father and his links to the Coromandel Coast were manifest through material possessions that were recognisably Indian. Ivory pieces were important in marking particular connections to geographical locations within the subcontinent. As noted in the Englefield Case Study, Richard Benyon (1698-1774) who worked as Governor of Fort St George between 1735 and 1744 purchased a very similar bureau to that owned by Harrison (see figure 6).[20] As with the textiles they purchased, these bureau cabinets linked these men and their families to Madras and the Coromandel Coast. Unlike the textiles they purchased, however, these valuable and highly valued cabinets remain as testimony to such connections. They have been passed down through generations and retain a strong sense of provenance.[21]

Not all ivory furniture pieces, however, stayed within East India Company families, East India Company servants also purchased them to be later gifted or sold. Moreover, while it was the East India Company elite who predominantly purchased ivory furniture in the early eighteenth century, in the later decades of the period, those (slightly) lower down the social ladder were also able to acquire such pieces. Evidence for the consumption of ivory furniture by those below the Governor rank can be seen through the example of Captain James Monro (1756-1806) who purchased a miniature cabinet with ivory veneers, made in Vizagapatam in the second half of the eighteenth century. Because it displays such an elaborate collection of ivory veneer sections, the piece can be dated to the post-1760 period when the majority of Vizagapatam ivory production shifted focus from ivory inlay work to ivory veneer (described above).

In researching the miniature cabinet, furniture historian Elizabeth Jamieson demonstrated how objects are sometimes able to allude to their histories.[22] On the sandalwood top of the lower section of the cabinet Jamieson found an inscription that reads ‘Out of No. 201 Houghton / Capt Monro’. The inscription connects the cabinet to the East Indiaman, the Houghton. Between 1766 and 1789 James Monro was a member of the crew on every voyage that the Houghton took. Monro, the third son of physician John Monro[23], began his seafaring career at the age of ten when he worked as a captain’s servant on the Houghton as it travelled out to trade at Whampoa near Canton. After this early engagement with shipping, Monro went on to work as midshipman and fifth mate on the Houghton before completing a further voyage as fourth mate on the Osterley II.[24] At the age of twenty Monro returned to the Houghton as second mate, a role he also performed on the York before finally gaining command of the Houghton for the first time in 1782. After this, James Monro captained the Houghton on three further journeys to Asia.[25] Perhaps most significantly for this case study, on his voyage to Bengal, as second mate on the Houghton, between 1777 and 1778 Monro stopped at Vizagapatam. The port had acted as an important English trading post or ‘factory’ since 1668. After 1768, however, when the Northern Circars came under the control of the English East India Company, Vizagapatam increased in importance as a place of settlement and a lucrative port for conducting Coromandel Coast trade in textiles.[26] Here Monro would have been able to see a range of ivory furniture pieces at first hand, perhaps encouraging him to purchase a piece later on when he became captain. As captain Monro would have been well placed to purchase pieces such as this (and to transport them back to Britain). With their popularity growing in late eighteenth-century Britain, such pieces would have proved a sound investment for private trade.

James Monro’s letters demonstrate that he purchased smaller items such as ceramics and furniture while on voyage, for gifting and sale once he returned to England. Writing to his elder brother Charles as he sailed from China to St Helena in November 1785, James described how he had managed to purchase some Chinese table and tea sets, as well as some small chairs.[27] He generously offered Charles and his new wife first refusal on his bountiful supplies.[28] Like other East India Company men studied in the East India Company at Home project (for example, William Gamul Farmer or Henry Russell of Swallowfield Park), James Monro appears to have depended upon his brother for support and information.[29] Even when in England, but away from the centre of news and markets in London, James requested Charles to complete payments and order clothes on his behalf.[30] After James’s death in 1806, Charles continued to play an important role in the life of his family. James’s wife Caroline (d. 1848) outlived him and Charles took responsibility for her and the remaining children. For instance, a letter from 1811 suggests that Charles was actively involved in managing the family’s financial affairs, particularly those of James’s daughters. He carefully ensured that household goods such as furniture were turned into investments such as an ‘Old South Sea Ann’ty’ and kept distinct from the ‘Estate’. After Caroline’s death it was these items and not the ‘Estate’ that would have been allotted to her daughters and Charles realised that they would ‘not be generally divisible’ or financially useful.[31] If the Vizagapatam cabinet remained in the family rather than being sold when James returned from India, it may well have been unsentimentally sent to market to provide for his daughters and their future life.[32] These ivory objects, bearing materials from the subcontinent and Africa, produced through the enactment of highly-skilled Indian craftsmanship to European designs, remained valuable and desirable commodities. Their links to the subcontinent through the EIC were part of their allure. Moreover, they often experienced an afterlife linked to, but independent of, their East India Company history. The next section of this case study considers that afterlife and examines what it might reveal about what these objects meant in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain.

[1] Paul Sangster, Balls Park, Hertford (Caxton Hill, Hertford: Hertford Press, 1972), p. 3.

[2] See Anthony Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers, 1600-1834 (London: The British Library, 1999), p. 355; Anthony Farrington, Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs 1600-1834 (London: The British Library, 1999), p. 359 and 515.

[3] Sir Charles Lawson, Memories of Madras (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1905).

[4] George K. McGilvary, East India Patronage and the British State: The Scottish Elite and Politics in the Eighteenth Century (London and New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 2008), p. 5.

[5] British Library, India Office Records, ‘Order and instructions to Captain Edward Harrison, Edward Herris and John Cooke, Supercargoes of the Kent, bound for Canton’, 1 December 1703, IOR/E/3/95, ff. 83-86.

[6] This is in contrast to ceramic goods, which are often difficult to identify with any clarity in inventories, as ‘The Willow Pattern Case Study’ demonstrates.

[7] Amin Jaffer, ‘Tipu Sultan, Warren Hastings and Queen Charlotte: the mythology and typology of Anglo-Indian ivory furniture’, The Burlington Magazine, 141:1154 (1999), p. 277.

[8] Jaffer, ‘Tipu Sultan, Warren Hastings and Queen Charlotte’, p. 278. BL IOR European Inhabitants in Bengal, 0/5/26.

[9] Jaffer and Corrigan, Furniture from British India and Ceylon, p. 172.

[10] As cited in Mildred Archer, Christopher Rowell and Robert Skelton, Treasures from India: The Clive Collection at Powis Castle (Great Britain: The Herbet Press, 1987), p. 84.

[11] Stacey Sloboda, ‘Displaying materials: porcelain and natural history in the Duchess of Portland’s museum’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 43:4 (2010), p. 464.

[12] Raynham Hall Archive, ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3. With thanks to the Marquess Townshend’s kindness in granting permission for information from the Raynham Hall Archive to be cited.

[13] ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3.

[14] ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3. See ‘The Harrison and Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, The Exceptional Sale, Christie’s, London, 7 July 2011, p. 61.

[15] British Library, Townshend Papers, An Inventory of the Right Honorable the Lord Lynn’s Goods taken at His Lordships House in Littel Grosvenor Street this 11 day of July 1737, Ms. 41656, ff. 209-10. See also ‘The Harrison and Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, pp. 61-62.

[16] Anthony Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers, 1600-1834 (London: The British Library, 1999), p. 793. He captained the Augusta on the following voyages: 1738/9, 1741/2 and 1744/5. See also ‘The Harrison and Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, p. 62.

[17] Raynham Hall Archive, ‘Letter from Augusta Townshend to Charles Townshend’, 24 December 1744, RAS B2/6.

[18] Raynham Hall Archive, A Journal of a Voyage from London to China on Board the Augusta Kept by Roger Townshend Anno Domini 1745, RAS H4/3.

[19] Raynham Hall Archive, ‘Letter from Charles Townshend to a brother’, 5 December 1747, RAS B2/6.

[20] Kate Smith, ‘Inheriting India’ in ‘Englefield House, Berkshire: processes and practices’, The East Indian Company at Home, 1757-1857’: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/englefield-house-berkshire/englefield-house-case-study-inheriting-india/ (2013).

[21] This strong sense of provenance can be seen in the marketing materials produced for the piece during its sale in 2011. See The Exceptional Sale, Christie’s, London, 7 July 2011, lots 14-17, pp. 60-78.

[22] Many thanks to Elizabeth Jamieson MA (Freeland furniture historian) for allowing me to include in this case study the research she completed for Bonhams.

[23] Jonathan Andrews, ‘Monro, John (1715–1791)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18976, accessed 21 May 2014].

[24] Anthony Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers, 1600-1834 (London: The British Library, 1999), p. 552.

[25] Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers, p. 552.

[26] Jaffer and Corrigan, Furniture from British India and Ceylon, p. 172.

[27] Elizabeth Jamieson mentions this letter in the research she completed on the cabinet for Bonhams. London Metropolitan Archives, ‘Letter written by James Monro to his brother Charles’, 22 November 1785, Acc/1063/034.

[28] In the letter James uses the advertising convention of ‘&c, &c, &c’ to note the range of items he has at his disposal. For more on this convention see Kate Smith, Material Goods, Moving Hands: Perceiving Production in England, 1700-1830 (Forthcoming with Manchester University Press), p. 62.

[29] This close relationship appears to be the case as a selection of letters between the two brothers survives in the archives of the London Metropolitan Archive. The survival of these letters suggests they were valued, but it might also be misleading in terms of the wider network James Monro established and used while working as a captain for the East India Company. See London Metropolitan Archive, Letters written by James Monro to his brother Charles ACC/1063/014-043 (1775-1790). Many thanks to Elizabeth Jamieson for the reference to these letters.

[30] London Metropolitan Archives, ‘Letter written by James Monro to Charles Monro’, 31 January 1780, ACC/1063/015.

[31] London Metropolitan Archives, ‘Letter written to Mrs Caroline Monro from her brother-in-law Charles Monro’, 14 January 1811, ACC/1063/121.

[32] For more on the inheritance of household goods by women see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ‘Hannah Barnard’s cupboard: female property and identity in eighteenth-century New England’, in Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel and Fredrika J. Teute, Through a glass darkly: reflections on personal identity in early America (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), pp. 238-273; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of An American Myth (Vintage Books: New York, 2002).