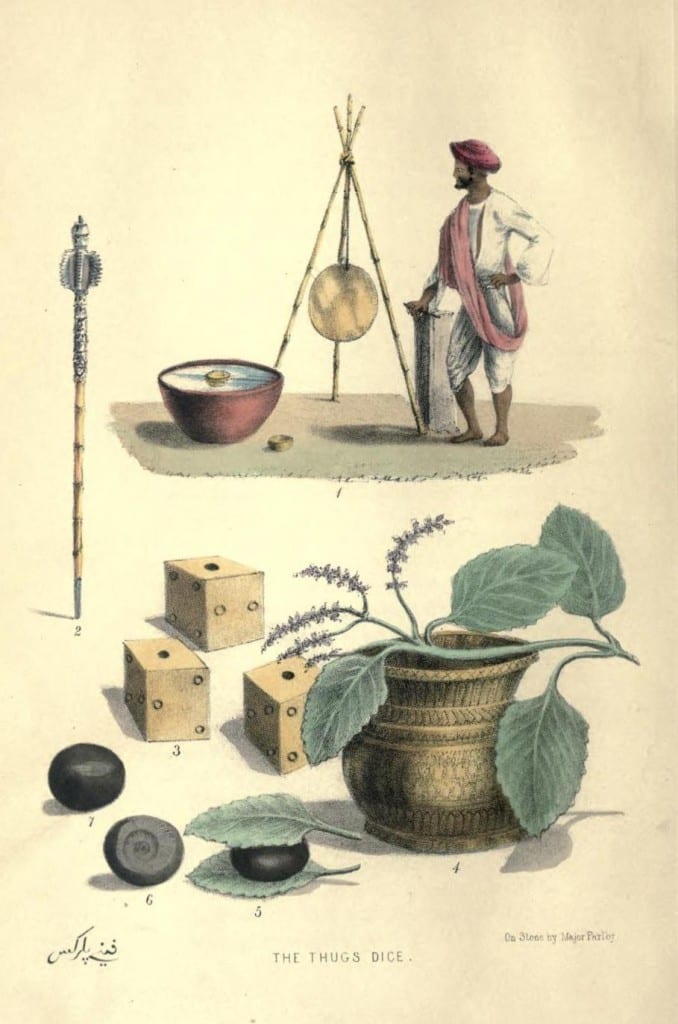

Figure 6. ‘The Thugs Dice’, Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. I (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). https://archive.org/stream/wanderingsofpilg01parluoft#page/n223/

The Cabinet of Curiosities

The cabinet of curiosities first appeared in continental Europe in the mid-sixteenth century, largely collected by the nobility, Frances Bacon writing that they were ‘in a small compass, a model of universal nature made private’.[1] They were essentially collections of artefacts, of anything that took the collector’s fancy, in what Tony Bennett has described as the ‘jumbled incongruity’ that was in time supplanted and surpassed by the museum.[2] In Germany they were called wunderkammer, in Italy stanzino, and there were collections in Russia. Britain was ‘notably absent’ from early lists of universal cabinets, although the royal gardeners, father and son John and John Tradescant, gathered together a collection of objects in the first half of the seventeenth century that was to become the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.[3] The first cabinets were literally that – a cabinet, in which small objects could be displayed. Later, as the collection grew, the display space was a specially designed room, until a collection became so big that it was impossible to show it in a single space. Sir Hans Sloane (1660 – 1753), for instance, collected over one hundred thousand objects and these were to form the basis of the British Museum collection.[4]

Tony Bennett extends Michel Foucault’s exploration of power and knowledge relations seen in the confined spaces of the asylum, the clinic and the prison to include the cabinets of curiosity that were essentially under private ownership and had restricted access to the privileged few. With public displays such as that of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the dioramas, and the panoramas of the first half of the nineteenth century, these restricted spaces were opened up to the public.[5] In this way, Fanny’s own Cabinet of Curiosities (or her Museum as she now termed it) was, after an initial period of confinement in her own home to be seen by the few, made available to visitors to the Grand Moving Diorama of Hindostan and seen by the many.

Fanny’s approach to collecting curiosities was unsystematic, driven more by an eclectic inquisitiveness, an enthusiastic grasping of the moment, than by the wish to build a well-organised group of objects illustrating defined aspects of Indian culture, as can be seen from the purchase of objects described below. Gavin Lucas has noted that, ‘One of the most striking aspects of much early collecting is the lack of distinction among objects; curiosities formed a generic group, where items such as fossils, butterflies, tribal weapons, and antiquities might all jostle side by side in a collector’s cabinet’ but adds that, ‘In a sense, the “fieldwork”, if one can use the term, of early modern collectors largely involved visiting other collections and dealers, rather than travelling to the source of such curiosities’, which was not true of Fanny who was usually to be found ‘travelling to the source’.[6]

These souvenirs of her time in India became more important to Fanny on her return to England. They represented a lived experience, and could be organised for her own private satisfaction, or for public view. Susan Stewart, in exploring the meaning of the souvenir, points to the way in which it ‘speaks to a context of origin through a language of longing… it is not an object arising out of need or use value; [but]… out of the necessarily insatiable demands of nostalgia.’[7] Fanny’s nostalgic needs were met not only by her curiosities, but by her writing about them, by sharing her longing through the medium of her published journals, and reliving the events through her ‘Grand Moving Diorama of Hindostan’.

Fanny appears to have begun collecting her curiosities in 1830, eight years after her arrival in India. She and Charles were by then living in the mofussil, in Cawnpore, a large station ‘on a bleak, dreary, sandy, dusty, treeless plain, cut into ravines by torrents of rain’ and unbearably hot.[8] The first item she acquired was a lathi, a large, heavy weapon made from bamboo, banded with iron, that had been confiscated from a man who had killed two others with it. Fanny reports that she took it ‘as a curiosity’, an impulse that seems to have motivated many of her object acquisitions.[9] Not long afterwards, in October 1830, she was given a set of Thugs’ dice by the acting magistrate in Cawnpore, the Thugs having been arrested and executed for the murder of thirty-five travellers (see figure 6).[10]

Figure 7. ‘A Kaffir Warrior’, Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. II (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). © British Library Board, General Reference Collection SFX lsidyv38ff8c09 II.

Her last purchase, bought in Cape Town in 1845 when she and Charles were on their way back to England, having left India for good, was a ‘kaross [cloak] of eighteen heads’ for which she paid four pounds. ‘It is very large and handsome,’ Fanny wrote, adding that: ‘With the exception of the kaross the Kafir is entirely unincumbered with clothing.’[11]

Most of her acquisitions, however, were made in Allahabad between the years 1831 and 1845, the great fair (now called the Kumbh Mela, although Fanny’s term for it is Bura Mela) held annually on the banks of the Ganges at its confluence with the Jumna being the site of enthusiastic commercial activity as well as intense religious worship – and where Fanny acquired many of her curioisities. This location, which even today is to Hindus one of the most sacred sites of their most sacred river, reaches a peak of religious significance every twelve years and is celebrated with a Maha Kumbh Mela which millions of pilgrims attend.[12]

On 2 February 1832 Fanny writes that she ‘went to the Bura Mela, the great annual fair on the sands of the Ganges, and purchased bows and arrows, some curious Indian ornaments, and a few fine pearls’.[13] But her ethnographic interest lies more broadly than curious objects, writing in the same paragraph about one of the fakirs (holy men) at the fair:

On the sands were a number of devotees, of whom the most holy person had made a vow, that for fourteen years he would spend every night up to his neck in the Ganges; nine years he has kept his vow: at sunset he enters the river, is taken out at sunrise, rubbed into warmth, and placed by a fire; he… is apparently about thirty years of age, very fat and jovial, and does not appear to suffer in the slightest degree from his penance.[14]

One year later, in January 1833, Fanny is once again at the fair, exclaiming at the area taken up by the booths, both for commercial and sacred purposes, and how it ‘attracts merchants from all parts of India… Very good diamonds, pearls, coral, shawls, cloth, woollens, China, furs, &c., are to be purchased.’[15] She relates an amusing story against herself, of how she bought a ‘remarkably fine’ pink coral necklace at this fair; and how some years later a friend of hers, a Mahratta lady, seeing her wearing the beads, exclaimed: ‘I am astonished a mem sahiba should wear coral; we only decorate our horses with it.’ Fanny immediately gave her necklace to her horse.[16]

Figure 8. ‘Superstitions of the Natives’, Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. II (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). © British Library Board, General Reference Collection SFX lsidyv38ff8c09 II.

The fair took place over a period of two months, offering many opportunities for finding curiosities. Amongst other things, she bought ‘a Persian writing-case, and a book beautifully illuminated, and written in Persian and Arabic: the Moguls beguile me of my rupees’ as well as two musical instruments and other ‘curious things; Hindoo ornaments, idols, china’, she reflected. [17]

It was at this fair that Fanny bought her most splendid and beloved curiosity, a huge white marble statue of Guneshu weighing some three hundredweight, painted and gilded. Growing wise to the ways of the merchants, she ‘sent a Rajput to the owner, and, after much delay and bargaining, became the possessor… The man had scruples with regard to allowing me to purchase the idol, but sold it willingly to the Rajput.’[18] Fanny relates that ‘Although a pukka Hindu, Ganesh has crossed the Kala Pani or Black Waters, as they call the ocean, and has accompanied me to England. There he sits before me in all his Hindu state and peculiar style of beauty – my inspiration – my penates.’[19]

Figure 9. Frontispiece illustrating Fanny Park’s collection of objects from the subcontinent. Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. I (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). https://archive.org/stream/wanderingsofpilg01parluoft#page/n5/mode/2up

Fanny clearly gained a reputation for collecting curiosities and frequently describes objects she has been given. In May 1832 she writes that a friend gave her ‘a pair of the most magnificent cow-tails, of the yak or cow of Thibet’, adding that ‘They are great curiosities, and shall go with my collection to England’.[20] These cow-tails feature in the frontispiece illustration to Wanderings of a Pilgrim, at its centre the huge marble Ganesh, and featuring the rarest and most interesting items from her museum – from the white marble statue of Ram to the ‘brazen image of Gunga’ represented by a woman sitting on an alligator (see figure 9). This idol is, according to Fanny, rare and valuable. ‘Victory to Gunga-jee!’[21]

Another ‘great curiosity’ sent to her by a friend was ‘a common dark brown-red shawl, worn by low caste women at Hissar. It is worked all over in large flowers, in orange silk; the centre of the flower contains a circular bit of looking-glass about an inch and a half in diameter… The appearance of the dress as the light falls on the looking-glass is most strange and odd… in what an extraordinary manner the light must be caught on all those reflecting circles of glass!’[22] Including this ‘low caste’ item in her collection shows that Fanny’s interest in textiles extended beyond luxury items and demonstrates her wide-ranging interest in Indian culture. One can only imagine how astonished she would have been to see skirts of this mirrored material being worn by young European women in the 1960s.

In March 1832 the Parks’ close friend Colonel Gardner stayed with the couple in Allahabad, much to their delight. While there, he taught them how to use an Indian bow and arrow. ‘Archery, as practised in India, is very different from that in England,’ Fanny tells us. ‘The arm is raised over the head, and the bow drawn in that manner: native bowmen throw up the elbow and depress the right hand in a most extraordinary style… A very fine bow has been given to me, which was one of the presents made by Runjeet Singh to Lord Wm. Bentinck… when strung, it resembles the outline of a well-formed upper lip, Cupid’s bow.’ Fanny adds that she ‘could not resist going continually into the verandah, to take a shot at the targets, in spite of the heat.’[23] This bow was undoubtedly one of the curiosities brought back to England, its origins adding lustre to the gift. Ownership of the bow, the narrative discourse of its acquisition, and the nostalgic memories it evoked, were more important to her than the object itself.[24]

Figure 10. ‘The Churuk Puja’, Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. I (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). https://archive.org/stream/wanderingsofpilg01parluoft#page/n77/mode/2up/

Fanny’s reputation as a collector brought visitors to her door, one being a German- Jewish convert to Christianity, Mr Wolff, who was keen to see her collection of Hindu idols.[25] Fanny had by this time been in India for eleven years and her knowledge of Hindu culture, the language and the rituals, had increased enormously since her arrival in the country. She would no longer feel, as she had early on in her residence in Calcutta, that she was ‘much disgusted’ by rituals such as the Churuk Pooja in which men swung from hooks pierced through their skin (even if she admitted that she was also ‘greatly interested’ by the sight) (see figure 10).[26] Her energetic pursuit of information had led her to become an expert – albeit an undisciplined one – in anything that took her interest. This expertise would give her cultural leverage when she returned to the metropole, and is an example of one of the ways in which British women came to benefit from empire.

One of the sculptures given to the India Museum on Fanny’s death was a piece of white stone on which a figure had been carved.[27] Fanny’s account of the circumstances in which she acquired it is very typical of her all-embracing enthusiasm. In March 1844 she and Charles were on their way back to India from Cape Town where Charles had been recuperating from some unspecified illness. The ship had dropped anchor off Pooree (now Puri) and Fanny had, as always, grasped the opportunity to go ashore. ‘A carved stone was presented to me, brought from the ruins of a city of great extent, about forty miles from Pooree; its name has escaped my memory, but it appeared from the account I received to be full of curiosities; few persons, however, had ventured to visit the ruined city, deterred by the probability of taking a fever, in consequence of the malaria produced by the thick jangal by which it is surrounded. The stone is white, and upon it is carved the figure of some remarkable personage, above which is an emblem of Mahadēo.’ She adds, demonstrating the jackdaw tendencies in her collecting, ‘A very fine tiger’s skin was also added to my collection. I carried off my prizes with great delight, and they now adorn my museum.’[28] It was this museum of curious objects that visitors entered after viewing the diorama.

The palimpsest of all these objects is clear, and even though their whereabouts today is unknown, Fanny’s brilliantly evoked images bring them vividly to the mind’s eye. But it is the curiosities that do have a known resting place in today’s metropole, albeit on the confined shelves of a museum’s basement, that are freighted with particular meaning. These are the two pieces of carved black stone that were presented to the India Museum on Fanny’s death and which are now in the British Museum collection (see one piece in figure 12).[29]

Figure 11. Image frame. Lower sections of an image-frame of Visnu in two parts showing attendant figures: (a) with a standing woman holding a musical instrument, and (b) with a standing woman holding a fly whisk; hand of Visnu above. Carved in dark grey sandstone. Twelfth century. Accession number 1880.35.39.a-b. (c) Trustees of the British Museum.

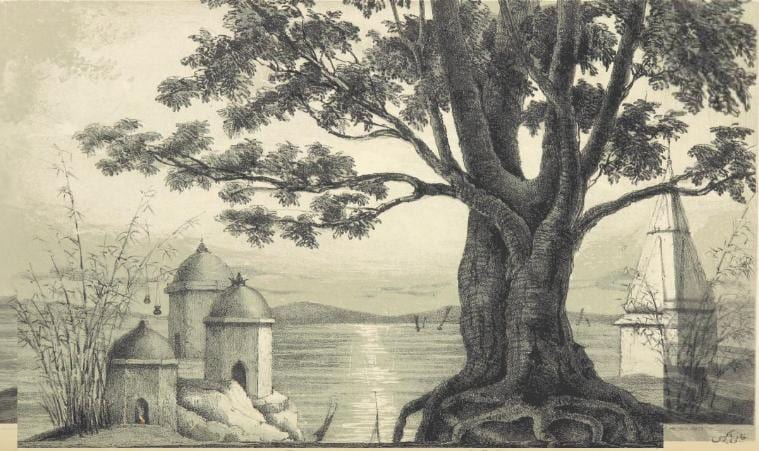

Figure 12. ‘Three Satis and a Mandap near Ghazipur. Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. II (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). © British Library Board, General Reference Collection SFX lsidyv38ff8c09 II.

Fanny’s description of these is lacking hard information but it is her account of how she acquired them and her comments on the place, the people, and the culture in which she found them that is especially revealing about the coloniser and the colonised. Fanny and Charles are taking the slow boat upriver to Allahabad from Calcutta in November 1844 rather than travelling the more rigorous overland dak route. This journey gives ample opportunity for exploration. Fanny writes:

Lugaoed at Barragh, a small village on the right bank: climbed the cliff in the evening; a fisherman who resided there showed me two sati mounds on the top of it, – the one built of stone sacred to a Brahmān, the other of mud in honour of a Kyiatt. A kalsā is the ornament on top of a dome; there were two of stone, without any points on the satī mound of the Brahmān; and two of mud, decorated with points, and one small image, on that of the Kyiatt.

I gave a small present to the people, and took away one of the kalsās of mud as a curiosity: a number of broken idols in black stone had been dug up, and placed on the satī mound of the Brahman, – I was anxious to have two of them, and determined to ask the fisherman to give them to me. The old man told me with great pride that one of his family had been a sati, and that the Brahmāns complained greatly they were not allowed to burn the widows, as such disconsolate damsels were ready and willing to be grilled…..

The Brahmānī ducks are calling to one another from the opposite banks of the river… The wind is down, there is a soft and brilliant moonlight, – the weather is really charming, and the moonlight nights delicious; from the high bank by the satīs one can see the stream of the Ganges below, glittering in its beams….

Ten P.M.; I have just returned from the satī mound, accompanied by the old fisherman, who brought with him two of the idols of black stone from the Brahmān’s mound… the old man gave them to me the moment I asked for them; I gave him a present afterwards, therefore he did not sell his gods; but he requested to be allowed to bring them to the boats during the darkness of the night. He and his family are now the sole inhabitants of a little hamlet of five houses… his four brothers… are dead, and their houses, which are in ruins, are close to the mounds; the old man lives in the centre, with one young son and two daughters, and keeps his dwelling of mud in comfortable condition. They tell me fowls and chakor (the red-legged partridge) are abundant there; I was unable to procure the latter.[30]

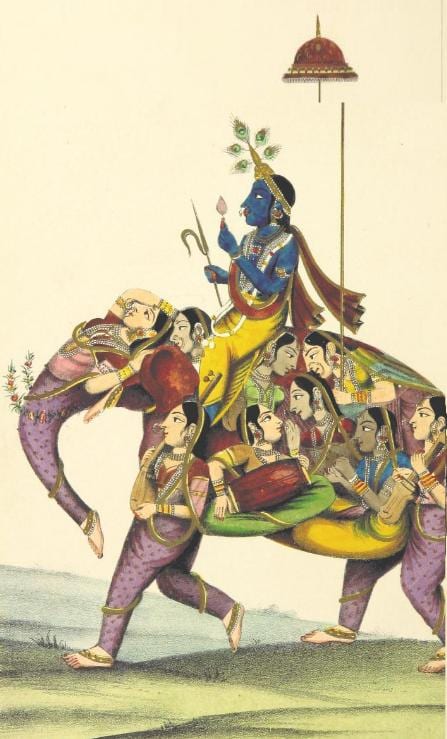

Figure 13, ‘Kaniyajee and the Gopees’, Wanderings of a Pilgrim in Search of the Picturesque, Vol. II (London: Pelham Richardson, 1850). © British Library Board, General Reference Collection SFX lsidyv38ff8c09 II.

I can picture Fanny, a rather stout lady now, not quite fifty years old, her head covered by an embroidered Indian shawl, her voluminous skirts hindering her progress as she puffs her way up the steep river bank to investigate the sati mounds. The old fisherman is thunderstruck by this vision of British colonialism, and even more so when she starts speaking to him in heavily accented Hindi. He has trouble understanding her as his first language is a local dialect, but nevertheless she charms him with her enthusiasm for the place. Though he is at first reluctant to answer her stream of questions about those women who brought honour to the family by becoming satī – she is an outsider, and a foreigner – to his surprise he finds himself talking to this strange woman who somehow reminds him of his long-dead bossy aunt. And when she says she wants to buy those broken pieces of stone that have been lying around for so long no one can remember where they came from or what they were for, he finds himself telling her he will bring them to her boat after dark. There are so many pieces, no one will notice and, in any case, he doesn’t want word to get around that he has money to spare now. He thinks the foreign woman must be a bit mad. What would she want broken stone for? What use can she find for the kulsā? Does she plan to put herself on the fire? Pre-dawn next morning he goes down to the water for his morning pūjā and watches the strange woman’s boat as it unties its lines and makes its way slowly up Mother Ganga. He wonders if he will ever see her again.

[1] Quoted in Arthur MacGregor, Curiosity and Enlightenment: Collectors and Collections from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century, (London: Yale UP, 2007), 11.

[2] Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, theory, politics (London: Routledge, 1995), 2.

[3] MacGregor, 17.

[4] Arthur MacGregor, ‘The cabinet of curiosities in seventeenth century Britain’ in Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor (editors), The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (London: House of Stratus, 2001), 201-15.

[5] Bennett, 73.

[6] Gavin Lucas, “Fieldwork and Collecting” in The Oxford Handbook of Material Cullture Studies, ed Dan Hicks and Mary C. Beaudry (Oxford: OUP, 2010), 231-2.

[7] Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narrative of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993), 135.

[8] Wanderings, I, 121.

[9] Wanderings, I, 132.

[10] The Thugs operated in gangs, strangling their victims. Wanderings, I, 151.

[11] Wanderings, II, 487.

[12] The 2013 Maha Kumbh Mela attracted 100 million pilgrims to Allahabad over a two-month period, thirty million of whom are reputed to have entered the holy water on one day, February 10th 2013.

[13] Wanderings, I, 227.

[14] Wanderings, I, 227.

[15] Wanderings, I, 253.

[16] Wanderings, I, 254.

[17] Wanderings, I, 261, 262.

[18] Wanderings, I, 262.

[19] Wanderings, I, xi.

[20] Wanderings, I, 238.

[21] Wanderings, I, 265.

[22] Wanderings, I, 239-40.

[23] Wanderings, I, 234-5.

[24] Stewart, On Longing, 136.

[25] Wanderings, I, 271.

[26] Wanderings, I, 26-8.

[27] V&A file MA/1/I108 India Museum Donations and Loans 1870 – 1879 N.F. Part II, item 11993 (original number 366).

[28] Wanderings, II, 385.

[29] British Museum item registration number 1880:3539.a-b.

[30] Wanderings, II, 417-8.