An Elusive Object

At all stages of its existence Chinese wallpaper has proved elusive. Although the Chinese pioneered the making of paper, c.105 AD they did not use the panoramic wallpaper as we know it in the West in their homes. It was designed as a European commodity. We know surprisingly little about Chinese craftsmen’s use of plain, coloured and patterned paper in the design of their intricate interiors. In 1664 when John Evelyn described the Chinese goods brought back by a Jesuit on return from China, he admired ‘a sort of paper … with such lively colours, that for splendour and vividness we have nothing in Europe that approaches it … [it is], exceeding glorious to look on’.[1]

It is likely that the Chinese wallpapers we know in the West originated from the less familiar wall decorations on paper created in China especially for export to Europe.[2] Chinese pictures were imported in small quantities first by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and then into France by Dutch traders, towards the end of the seventeenth century.[3] The earliest precise reference to the import of graphic art from China to England is 1727.[4] There is a detailed description of these pictures by Robert Fortune (1812-1880), the plant hunter who found time during his travels in China to observe in the house of a mandarin of Tsee-kee, ‘a nicely furnished room according to Chinese ideas, that is, its walls were hung with pictures of flowers, birds, and scenes of Chinese life. . . . I observed a series of pictures which told a long tale as distinctly as if it had been written in Roman characters. The actors were all on the boards, and one followed them readily from the commencement of the piece until the fall of the curtain’.[5] These pictures continued to be popular in Britain and were used alongside Chinese wallpaper. For example at Fawley Court, Henley-on-Thames in 1771 a dressing room was decorated with ‘the most curious India paper as birds, flowers etc., put up as different pictures in frames of the same’.[6] Lady Cardigan bought 88 ‘Indian pictures’, in 1742 which were pasted over the walls of a dining room.[7]

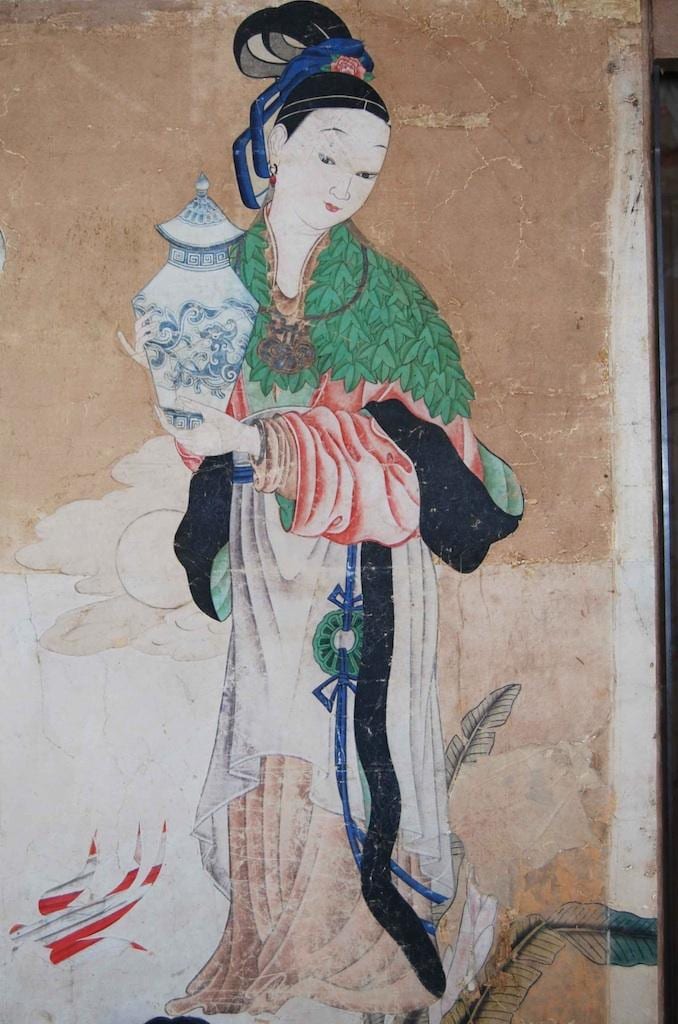

Figure 2. Detail of one of the 60 Chinese pictures used as wallpaper in what is now the Study at Saltram, Devon (National Trust). Picture courtesy of Andrew Bush.

Some wallpaper was in fact painted on silk not paper.[8] It was ‘probably hand painted in the same workshops in Canton since the technique to stain wallpapers was very similar to the preparation of hand painted silks’.[9]Like the textiles with which they were associated, including Indian-made chintz, Chinese wallpaper was admired in the West for its colour. We know that many interiors combined the two, for example at Harewood House, near Leeds the room with the ‘Chints [bed] Hanging lined with silk’, was hung with Chinese wallpaper. This was a European-wide phenomenon. In Italy the casinos were ‘neatly fitted up with India paper, and furnished with chintz’.[10] Chintz patterns were even drawn from Chinese wallpaper, as the chintz valence for David Garrick’s bed demonstrates.[11] Malachy Postlethwayt (?1707-1767), in his Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce (1757) ascribed the popularity of Chinese export paintings to their colours, diversity and fantasy, ‘the pictures are valued for the liveliness and briskness of the colours and variety of figures. Odd fancies commonly hit the general taste, and the Chinese do not seem to have any fancy for pieces of gravity’.[12] Hargrove and Bewick described the best bedchamber at Newby Hall, near Ripon in 1789 as ‘hung with India paper, on which the flowers and foliage, birds and other figures, are represented in the most lively and beautiful colours’.[13] Here the word ‘lively’ indicates vibrancy. It was the bright colour of Chinese wallpaper, that according to the wallpaper maker John Baptist Jackson (c.1701-c.1780) revolted against the notion of taste: … ‘the gay glaring colours in broad patches of red, green yellow blue etc which are to pass for flowers and other objects which delight the eye that has not true judgment belonging to it’.[14] Other distinctive qualities of Chinese wallpaper were its smoothness, opacity and uniformity, akin in some ways to the European fascination with porcelain.[15]

While Europeans admired what they thought was the fine art of Chinese hand-painted paper, it is clear that techniques such as block printing were used.[16] Even when they were entirely hand-painted, the production process was highly organised and sub-divided, which speeded up production. As the conservator Pauline Webber has noted ‘Chinese wallpapers were manufactured in production-line workshops. Working to a copied design and with labour divided according to skill, a team of painters produced sets of wallpapers to decorate entire rooms’.[17] Clare Taylor reminds us that these papers ‘formed part of a growing consumer market’, stimulating imitative innovation.[18] Yet the relationship between Chinese and European wallpapers was not a simply imitative one. Chinese wallpapers do not, like armorial porcelain, appear to have been made to commission, where western designs, such as bookplates, were sent out for copying, nor were they made to ‘fit’ specific rooms, as extensive modifications to Chinese wallpapers at top and base, and with cut-outs pasted on to hide joins prove. Some examples show evidence of skies painted in, or strips added at the base, like the paper at Milton Manor, Oxfordshire. There is only one example of a Chinese wallpaper being made to a European design, from engravings by the French designer of ornament Gabriel Huquier (1695-1772) after the French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), made for Hampden House in Buckinghamshire, and hung around 1756.[19]

Figure 3. Detail of block printed outline, from Chinese wallpaper at Felbrigg, Norfolk, supplied by James Paine in 1751, and hung in the Chinese bedroom.

Photograph courtesy of Andrew Bush.

Chinese wallpapers were rare novelties, expensive, and looked very different from the tapestries and textile hangings which preceded them. Lady Anna Rys Miller, noted in 1776 that ‘India paper is more expensive in England than damask here [in Italy]’.[20] At Croome Court in Worcestershire the bills for the ‘29 fine India landscapes’ of 1763 sent to Lord Coventry reveal each landscape cost £2 2s each, making a total of £60 18s, equivalent today to £4,000.[21] It was so expensive, offcuts were kept, as at Penryhn Castle, Gwynedd, and old papers removed and put into storage.[22] ‘Occasionally sets of eighteenth-century Chinese wall-papers are discovered in attics and lumber rooms, which have never been fixed on to walls, but are still in the neat boxes of Chinese manufacture in which they were sent to this country. These boxes generally contain twelve lengths. The explanation seems to be that the owners, having no immediate use for them, stored them away’.[23] Part of the attraction of these papers was their rarity, as Lady Mary Coke commented in 1772 ‘I have taken down the Indian paper, put up another upon a blue ground with white birds & flowers: ‘tis very pretty & has the additional recommendation of being quite new. There are but eight sets come to England’.[24]

The display of Chinese wallpaper signalled participation in the new consumer revolution, and became part of a popular mercantilist trope, which set honest home-made goods against deceptive foreign imports that threatened the Nation’s economy and morals: ‘Luxury is become general. To observe the furniture of our houses with gilded ceilings, the hangings of India paper, rich silk damasks tapestry and velvet, the large French and Venetian glasses’.[25] In an article in the popular magazine The World of 1753 the author bewailed the fact that ‘the upper apartments of my house, which were before handsomely wainscoted’ were now adorned ‘with the richest Chinese and India paper, where all the powers of fancy are exhausted in a thousand fantastic figures of birds, beasts, and fishes, which never had existence’.[26]

Chinese wallpapers were often, although not always, pasted to textile linings (after the ‘canvas’ had been lined with European paper) tacked onto wooden strainers secured to the unfinished walls with nails. The use of a textile support not only provided a flat surface but also enabled the wallpaper to be removed if the decorative scheme was changed. Given the expense of these papers, mobility was an important feature, and it also kept them dry in often damp British country houses. However it is evident that most inventory makers considered these papers as fixtures, rather than moveable chattels, so they do not always appear in these documents. Yet there is a great deal of evidence to show how these wallpapers moved about, within a house, and from house to house. The Chinese wallpaper at the Court of Noke, Herefordshire came from Lambton Castle, County Durham. The Chinese wallpaper at Harewood, Leeds hung by Thomas Chippendale in 1769 had been removed by the 1840s, and was later discovered in an outbuilding on the estate in 1988.[27] Others, like that at Croome Court, were sold at auction.[28]

Although imported by the East India Company, Chinese wallpaper, like hand-painted silk, was part of the private privilege trade, and never part of official Company trade, at least for the English East India Company. That is, it was part of the allowance given to employees, the captains, merchants and supercargoes, who were paid modest salaries, and were permitted to trade on their account to specified levels, which allowed the most successful to increase their income thirty-fold.[29] However all these private purchases had to be put through the East India House auction in London, levying an auction commission of 15 per cent (or sometimes more) on the prices realised. Thus a private trader had to buy back the goods he had financed if he wanted them. As David Howard reminds us ‘These private traders were socially and financially in touch with wealthy private clients, who might often be related by blood, and it was they who elected the most fashionable products available at Canton by carrying special commissions. They gained a much wider understanding of what was available, which knowledge was in turn, at the disposal of the Company’.[30]

Yet this private trade accounted for no more than 10 per cent of the whole trade with China (and usually much less). Unfortunately as the privilege trade was not fully documented, and most of the auction records have been lost, it is difficult to pursue more detailed research. If Chinese wallpaper remained marginal in commercial terms compared to Company trade, the latter in turn needs to be put in context. As Jan de Vries has argued, even the Company trade only equated, by the later eighteenth century to around 50,000 tons per year, (equivalent to the capacity of one modern container tanker).[31] What was important about these goods was not their volume, but the impact they made, which was quite disproportionate to their number.

[1] Henry G. Bohn, Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, F. R. S., Volume 1, (London 1859), p.402.

[2] I. Lambert & C. Laroque, ‘An eighteenth-century Chinese wallpaper: historical context and conservation’ in Works of art on paper: books, documents and photographs: techniques and conservation: contributions to the Baltimore Congress, 2-6 September 2002, p.122-128. See:https://www.iiconservation.org/node/2202

[3] Quoted G. L. Hunter, Decorative textiles: An illustrated book on coverings for furniture, walls and floors (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1918), p.363.

[4] Craig Clunas, Chinese Export Watercolours (London: V&A, 1984), p.10.

[5] Robert Fortune, A Residence Among the Chinese (London: John Murray, 1865), chapter 4.

[6] Emily J. Climenson (ed)., Diaries of Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys of Hardwick House, Oxon, (London: Longmans, 1899), pp. 146-147, entry for October 1771, quoted in Saunders 1994, p. 49, note 15.

[7] Quoted in Margaret Jourdain and Soame Jenyns, ‘Chinese export art in the eighteenth century’, Country Life, 1950, p.34.

[8] Ceri Johnson, ‘Chinese Wallpapers at Saltram’, Devon Buildings Group Newsletter, 15 (Easter 1997), pp.6-11.

[9]Vanessa Allayrac-Fielding, ‘Luscious Colors of Glossy Paint’: The Taste for China and he Consumption of Color in Eighteenth Century England’ in Andrea Feeser, Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin, The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400-1800 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), p. 85.

[10] Lady Anna Rys Miller, Letters from Italy, describing the Manners, Customs, Antiquities, Painting, vol.2 (London 1776), p.358.

[11]Victoria and Albert Museum, W.701-1916. Painted and dyed cotton, Coromandel Coast, c.1774, replicas on display in the British Galleries room 118a, case 1.

[12] Quoted in Feeser , The Materiality of Color, p.86.

[13] E. Hargrove, The History of the Castle, Town and Forest of Knaresborough with Harrogate, (4th edn, York 1789), p. 265

[14] Quoted in A.V. Sugden, A History of English Wallpaper 1509-1914 (London: Batsford, 1914), p.56.

[15] Pauline Webber, ‘Chinese wallpapers in the British Galleries’, V&A Conservation Journal, 39 (2001).

[16] George H Morton, paper read before the Architectural and Archaeological Society of Liverpool, 1875 ‘… the Chinese and Japanese Paper Hanging are occasionally brought home at present time. They are probably partly printed and afterwards finished by hand’.

[17] Pauline Webber, ‘Chinese wallpapers in the British Galleries’, p.6.

[18] Clare Taylor, ‘Chinese Papers and English Imitations in 18th Century Britain’, from E. Stevenow-Hidemark (ed) New Discoveries New Research: Papers from the International Wallpaper Conference, Nordiska Museet, Stockholm, 2009. p.36.

[19] John Cornforth, Early Georgian Interiors (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), pp.265-6.

[20] Miller, Letters from Italy, p.23.

[21] Liza Picard, Dr Johnnson’s London (London: Phoenix Press, 2001), p.297

[22] Gill Saunders, ‘The China Trade: Oriental Painted Panels’ in Lesley Hopkins (ed) The Papered Wall: History, Pattern Technique, (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994), pp. 42-55, with thanks to Andrew Bush for this reference.

[23] http://www.historic-house.org/history/part2/history-80.html. See five wooden boxes and fifteen boards, c.1815, part of the cargo of the Diana, which sank off Malacca in 1817, A Tale of Three Cities, Canton, Shanghai & Hong Kong, Sotheby’s, London, 1997, p.33.

[24] The Letters and Journals of Lady Mary Coke, vol.4, 1772-74 (Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1970), p.43.

[25] The London Magazine, vol. 42, 1773, p.69

[26] The World, September 20, no.38, vol. 1, 1753, p.245.

[27] Thanks to Mellissa Gallimore for this information.

[28] Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush and Helen Clifford, Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses (National Trust, 2014), no.12, p.22 (sold in 1948)

[29] See further, ‘The Honourable East India Company trading to China’ in David S. Howard, A Tale of Three Cities Canton, Shanghai & Hong Kong, Sotheby’s, London 1997, p.xiv.

[30] Howard, 1997, p.xiv.

[31] Jan de Vries, ‘Goods from the East’, p. 30, forthcoming in Maxine Berg et al (eds) Trading Eurasia Europe’s Asian Centuries 1600-1830 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).