A gendered division of labour appears to have reigned in Calcutta’s distinctive European consumer markets. Auction houses appear to have been male domains in which Indian men consumed alongside European men. European women, in contrast, were proscribed from Calcutta’s auction houses in the nineteenth century. Sir Charles D’Oyly’s 1828 depiction of an elite emporium underscored both the conspicuous presence of women and the conspicuous absence of propertied Indian consumers.

By the time the Russell family had purchased Swallowfield and begun to refurbish it in 1826, they were already experienced at procuring furniture and furnishings. How? While in India, Sir Henry’s eldest sons, Henry and Charles, received an early education in the importance of domestic decor. Sir Henry’s house in Calcutta functioned as a clearinghouse for goods sent to and from his sons in south India. It was through this channel that Henry and Charles received fashionable goods from their kinfolk in England, and through this conduit too that the brothers sent gifts of exotic luxuries to their political patrons at home.

Equipping his sons with appropriate domestic goods as they established their imperial careers was a task that Sir Henry took seriously. When Charles was appointed to a junior post in Hyderabad in 1804, his father sent him household items by sea from Calcutta. The list of these goods underlines the Russells’ ambitions to genteel status: it included a writing table, a chest of drawers, a stand for a chillumchee (basin for washing hands), a looking glass, book shelves and language and history books.

In later years, father and sons learned from each other. Sir Henry had travelled to Hyderabad shortly before sailing to England, and the magnificence of his son’s palatial residence there had clearly captured his imagination. When he returned to England in 1814, Sir Henry promptly took his daughters to the continent to shop.

For more on ebony furniture, go to our case study. Objects such as these exotic ‘oriental’ goods piqued the interest of British consumers in the sub-continent, encouraging families to send their sons into the East India Company service. By the eighteenth century there was a well-developed market for the Indian production of furniture in European forms, of which the Russells were avid consumers.

As a result of the continental shopping expedition, Sir Henry’s house at Wimpole Street was decorated richly and tastefully. He later wrote to Charles, ‘is magnificently furnished; the clocks, candelabras, & vases, which we brought from Paris, added to the Ebony Chairs, crimson & gold curtains…large Mirrors, & several beautiful cabinets, make it really very superb & the taste of Caroline has preserved aptness & uniformity in the colouring’. [1] Eschewing the Asiatic styles of chinoiserie for French furnishings may have been a sensible strategy for Sir Henry’s re-immersion in Georgian culture and society. Caricatures of the tastelessness and effeminacy of ‘Oriental’ excess were widely pervasive in English literature and culture at this time.

But was French taste really perceived very differently in this period? Also by the early nineteenth century many chinoiserie motifs had been normalised into a British aesthetic that regarded them as quintessential to the national identity (for example willow pattern wares). So how were these objects regarded? What did they mean?

For the next several years Sir Henry headed a household that—until their marriages—included his four surviving daughters, Caroline (1792-1869), Kate (1795-1845), Henrietta (b. 1797) and Rose (1800-1889). His two youngest sons, the clergyman William Whitworth Russell (1795-1847) and the lawyer George Lake Russell (b. 1802), visited Wimpole Street when not away at school or university.

Trialling their taste

While in India Henry and Charles mainly consumed Indian wares, but on returning to Britain they went straight to continental Europe to consumer luxury goods, perhaps such as this stool, there.

After cutting their teeth on early projects, Henry and Charles had the opportunity to put their education to use in 1810 when Henry became Resident at Hyderabad. Prior to this appointment, however, Henry had already taken the opportunity to furnish a house when he married Jane Casamaijor in 1808.

Although the East India Company had earlier discouraged the arrival of European women, by the early nineteenth century colonial Madras had both a flourishing (if small) marriage market and a thriving consumer culture inspired by conceptions of fashionable gentility. Charles suspected his brother of harbouring matrimonial intentions when in 1808 Henry wrote to him requesting that Charles send ‘the large Bed, with the Bedding, [and] the net Counterpane’ which he had left behind in Hyderabad. Henry acknowledged that ‘The Precision of my Orders about the Bedding and Irish Net was certainly very suspicious’, but hastened to deny that these instructions were a token of his intentions toward ‘the charming Jane’ Casamaijor. [2]

In the event, in October Jane and Henry indeed married, and settled into a home that Henry had furnished with lavish abandon. Jane’s agonising death from a tropical disease in December led to Henry’s dispersal of these marital goods, which reminded him too painfully of his loss. In January 1809 Henry wrote to Charles announcing that he would sell off his furniture and plate. [Similarly, when Richard Benyon, Governor of Madras lost his wife Frances in 1742 he responded by ridding himself her belongings.]

His subsequent letters detailed his sale of items that were the height of Madras fashion at the time, blending venerable European motifs with the current craze for all things Egyptian. The list of goods he disposed of underscores the importance of colonial consumption in shaping the domestic tastes of Company men. Items sold by Henry included twelve black varnished chairs with a red Etruscan border, a twelve-foot long ottoman covered in chintz, a bookcase with Egyptian bronze figures, two couches in the Egyptian style and ‘a pair of the newest fashioned Sofa Tables on Pillar Legs inlaid with Brass and fitted up with Brass Ornaments’.

A Formidable Team

Mahogany is mainly found in the Americas and West Indies islands such as the Bahamas. In making The Denon Chair, Jacob-Desmalter used mahogany to create Egyptian style furniture, which became hugely popular during the Napoleonic wars. Henry and Charles Russell were first introduced to this style in India and then continued their interest in it when back in Britain.

After a brief interval in Pune, Henry was at last appointed to the Hyderabad Residency. Hyderabad, where Charles and Henry lived together for nearly a decade upon Henry’s appointment as Resident in 1810, afforded the brothers a rich canvas for domestic design. It was here that they developed a dynamic partnership, carefully calculated to deploy material culture to establish their family’s social status and political power. This domesticating campaign of familial aggrandisement was later rehearsed and refined in the brothers’ collaborative project to establish Swallowfield as the Russells’ English family seat.

Although Hyderabad’s fortunes were on the wane by the early nineteenth century, the city and its surrounding state remained a vital centre of wealth, luxury and power in this period. Its opulence fed in part by the diamond trade, Hyderabad was known for its rich bazaars and elegant pleasure gardens. The British Residency was located opposite the old city, across the river Musi, a site now occupied by the Osmania University College for Women .

.

Both Henry and Charles had served at Hyderabad during the Residency of James Achilles Kirkpatrick (1764-1805; Resident 1797-1805). In 1800, Kirkpatrick conceived an ambitious building campaign, which within a few years transformed the Residency into a Palladian palace notable for its combination of European and Indian stylistic elements. But the Residency’s new structures, ornamentation and furnishings also emphatically pronounced the Company’s waxing power in Hyderabad. The house itself boasted a grand salon, a gallery with a painted ceiling and a chandelier that had been sold to the Company by the ever-indebted Prince of Wales—in whose Orientalised fantasy, the Royal Pavilion, Brighton

Both Henry and Charles had served at Hyderabad during the Residency of James Achilles Kirkpatrick (1764-1805; Resident 1797-1805). In 1800, Kirkpatrick conceived an ambitious building campaign, which within a few years transformed the Residency into a Palladian palace notable for its combination of European and Indian stylistic elements. But the Residency’s new structures, ornamentation and furnishings also emphatically pronounced the Company’s waxing power in Hyderabad. The house itself boasted a grand salon, a gallery with a painted ceiling and a chandelier that had been sold to the Company by the ever-indebted Prince of Wales—in whose Orientalised fantasy, the Royal Pavilion, Brighton (left), it had previously hung.

(left), it had previously hung.

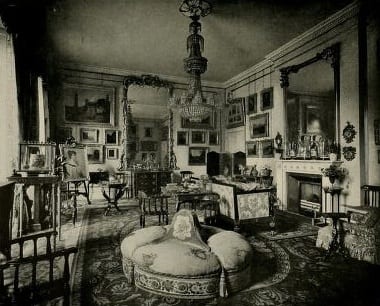

‘The Library, Swallowfield’, in Lady Russell, Swallowfield and its Owners (London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green and Co., 1901). This image depicts the library (or rather the structure of the library) that the Russells finally owned at Swallowfield. Its sheer size demonstrates how the library remained an important space for these East India Company officials.

Henry Russell took up residence at Hyderabad only in 1811, but was keen to stamp the Residency with an elite European impress. He wrote to Charles that he was willing to pay Sydenham (Resident of Hyderabad between Kirkpatrick and Russell) a thousand pounds for his library, and was also happy to purchase his predecessor’s sporting prints. The Residency’s library projected with particular force Henry’s determination to be numbered among the empire’s gentlemanly elite. Forty feet long, it included busts of the ‘Ancients’ on one side and the ‘Moderns’ on another. Here the knowledge systems that underpinned colonial power were encapsulated in sculptures that depicted Aristotle, Homer, Cicero, Shakespeare, Milton, Newton, Locke, Burke, Fox and Pitt. [3] At the same time, new furnishings were ordered from Calcutta’s select emporia: on 29 August 1810, Henry informed Charles that as the Residency’s alterations reached completion he had resolved to purchase ‘an entirely new Set of Furniture adapted to it from Calcutta’ and wished to have Charles’s advice on its selection. Upon returning to Britain, Henry was to devote substantial effort to fitting out a similarly capacious library at Swallowfield.

In fitting out the Hyderabad library, what might a ‘Set of Furniture’ ‘from Calcutta’ have been like? What was Calcutta famous for in this period?

The purchase of fashionable European goods threw Henry upon the mercy of his Casamaijor in-laws. He remitted £3,500 to Elizabeth Casamaijor (Jane’s mother) in London, and reported happily on 26 June 1812 that she had despatched busts, glassware and china to him on the William Beasley and City of London. The goods were shipped to Madras, to be forwarded to Henry from Madras by his deceased wife’s father, yet another example of the key roles played by family and in-laws in mediating colonial consumer relations. [4]

The furnishings selected by Henry were not uniformly European. His prints of fox-hunting, for example, were complemented in the Residency by pictures depicting scenes from the Arabian Nights. But European styles and motifs increasingly supplanted Kirkpatrick’s more cosmopolitan furnishings. Henry’s furniture included gilt chairs, ‘splendid beyond anything I could conceive’, as he wrote to Charles, while ‘Wilton’s Vases are very elegant, and exquisitely worked’.

Design. England, C18th, William Chambers. Pen and ink, pencil and grey washes, 8169. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Here is a similar design to the one produced for the vases at Wilton House, perhaps this is what Charles referred to when describing his vases as ‘Wilton’s vases’.

The design above was drawn by William Chambers, an architect who also produced similar drawings for Wilton House. Were ‘Wilton’s vases’ made in imitation of those at Wilton House?

By the time that Henry (in some disgrace) left India for England in 1820, the Residency had gained international renown for its magnificence. Its splendour was celebrated in countless engravings, lithographs and watercolours in the following years, a reputation that Henry was keen to burnish.

The two brothers continued to negotiate purchasing decisions together. January 1822 saw Henry write to Charles from Paris, where he and Clotilde had already begun their campaign to furnish their prospective home. Here Henry acquired bronze horses for 1,500 francs and a chest of drawers for 500 francs, holding back from other purchases only because he lacked a house in which to put them. As in Hyderabad, he relied on Charles for furnishing advice. ‘I wait for your Opinion before I decide whether to buy some pieces of very fine Bowle [sic: boulle] Furniture which are for sale here’, he commented to his brother, supplementing this plea with instructions for a vase, adorned with an elephant’s head, that he had commissioned to be made in London. [5]

The Hyderabad Residency had, however, set a high bar for the Russell family in England. Establishing an English country seat that could match Henry’s Indian home was to tax the Russell men’s financial and cultural capital heavily in the next quarter of a century.

[1] Sir Henry Russell to Charles Russell, 25 January 1816, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. c. 152, fol. 234 verso.

[2] Henry Russell to Charles Russell, 9 March 1808, Bodleian MS. Eng. lett. c. 155, fol. 128, and Henry Russell to Charles Russell, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. c. 156, fols. 3 verso-4.

[3] Henry Russell to Charles Russell, 26 September 1814, Bodleian, MS. Eng. let. c. 157, fols. 92 verso-93; Henry to Charles, 1812, MS. Eng. lett. d. 152, fols 252-252 verso; Sir Henry Russell to Lady Anne Russell, 11 February 1813, MS. Eng. lett. c. 153, fols 28-29.

[4] Henry Russell to Charles Russell, 27 May 1810, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. d. 151, fols 87 verso-88; Henry to Charles, 31 May 1810, MS Eng. lett. d. 151, fol. 95; Henry to Charles, 29 August 1810, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. d. 151, fols 228 verso-229 verso; Henry to J.H. Casamaijor, 26 June 1812, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. d. 163, fols 119-119 verso; Henry to J.H. Casamaijor, 18 July 1812, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett. d. 163, fol. 126 verso.

[5] Henry Russell to Charles Russell, 12 January 1822, Bodleian, MS. Eng. lett., c. 157, fols 152 and 154. See also Robert Grindlay’s, Scenery, Costumes and Architecture, Chiefly of the Western Side of India (London, 1830), vol. 2, plate 19 in BL A&AS Prints, among other places.