Hall as Prisoner of War & His Great Escape

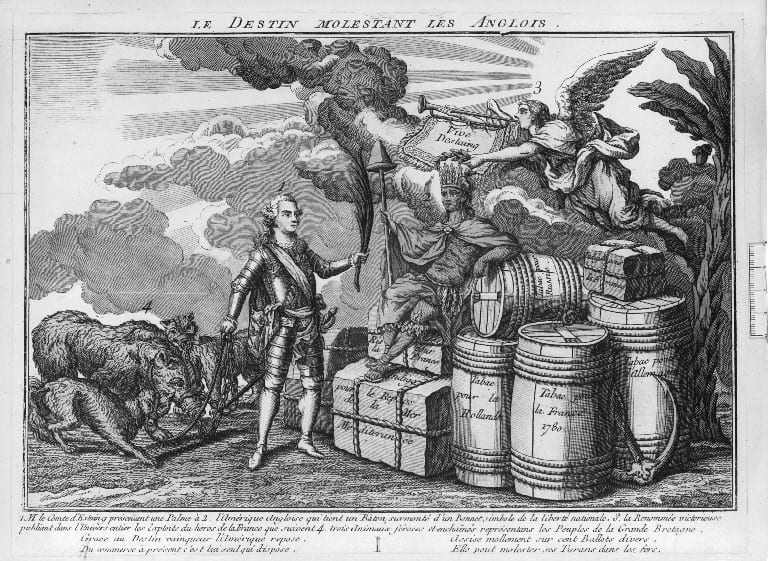

Hall’s thwarted desire to make a ‘competency’ along with the omnipresent threat of death was made worse by the near constant threat of attack from Dutch, Malay or French forces. In 1755 he joked to his sister that they required assistance from their sailor brother Robert: ‘he would have assisted us when we were in danger from the Mallays & Alchun[?] men, who were pushed on against us, by our good friends & Allies the Dutch So that you have once prophesied true that our penknives are turned to Swords & our Pepper Corns into cannon Balls but however now as we have got the advantage I hope every thing will return to its primitive state’.[1] Any peace was short lived. In 1760, two French ships under the command of Count D’Estaing took Alexander Hall prisoner at Natal before going on to attack Fort Marlborough. Hall and many of his fellow factors were sent to the Dutch settlement at Padang, some 300 miles south-west of Bencoolen, and remained there ‘without any means of Subsistence’ for five months.[2] While there, the British men tried to get on a Dutch boat to reach the Coromandel Coast but were informed ‘it was a Standing order of the Dutch Company never to admitt [sic] Foreigners to take Passage on board of their Vessels’[3]. Instead, Hall and William Wyatt, the two most senior civil servants, petitioned Christian Ludowick Senff and Frederick Van de Wall, the Governors of Padang, for 2800 Spanish Dollars to purchase a boat.[4] They left Padang by this boat on 25 August 1760 and reached Masulipatam on the 30 October. They stayed there until the end of the monsoon season before embarking on the short journey to Madras. Before they reached Madras, however, the vessel was wrecked near Nellore, ‘where everything was lost but Cloaths and a Chest of Treasure’. After this misfortune, the nearby Nabob Nasum Boolee Chan gave them palanquins, camels and coolies which carried them to Madras.[5]

Despite his repeated petitioning of George Pigott, Hall could not get exchanged at Madras and freed from the terms of his parole. Instead, finding he could not work, Hall decided to return to Europe—a set of events he begrudged as ‘[I] do not see anything to have hindered our exchange or Release long ago at Madras but the Governour [sic] there, by the bye no better than he should be, had a Pick against all our Establishment & he resolved to persecute us which he has done to his utmost’.[6] While this incident further interrupted Hall’s desire to make a ‘competency’ it did, however, help reverse his increasing estrangement from his family after an absence of twelve years from Britain. He wrote to his brother in April 1762, ‘You will no doubt be a good deal surprised, and I daresay agreeably, to see this dated from London, its really so however, for I arrived at Plymouth in the Falmouth Indiaman the 6th inst’.[7] Hall was conflicted about the wisdom of returning to Britain: ‘Already I have drawn this comfort from my Voyage, that, were it not for the Pleasure of being with you & the rest of my friends in Scotland, I would immediately transport my self again to India, for I am heartily tired of — even London. … As for my part I can’t say I wish that we should all meet in this place of Dissipation, in Dunglass indeed it would be a Blessing.’[8] This dislike of ‘dissipated’ London was increased by Hall’s engagement with the serpentine windings of the East India Company bureaucracy. In March 1762, he submitted a minute to the Directors, requesting they would pay off the 2800 Spanish Dollars he had borrowed from the Dutch at Padang. Eventually, the Directors appear to have grudgingly agreed, even while they refused to pay for Hall’s return passage to India.[9] Hall was released from the conditions of his parole in June 1762, but he decided to wait until the following year before returning to India, ‘to spare my self the Trouble & Risk of my Health in resettling the West Coast & to be with my friends once more in my Life: So I expect to be with you in about [a] Month & stay all Summer with you, return [ag]ain to India but God know when to return’.[10]

Before he left London, Hall petitioned Lord Shelbourne in 1762 to be transferred to Bengal Presidency. He was refused on the grounds that his knowledge of Sumatra was too valuable for the Company.[11] Hall however did not give up this attempt for an exchange to Bengal and wrote to his brother John from India: ‘On account of the great loss of Companies Servants at Bengal lately, I have renewed my request to go there as I daresay they will be send[in]g Gentlemen in pretty high Rank. I have wrote it to (dont be angry) Ld M__t & Mr Crompton who assisted me before … I also begg of you to see what you can do, to get me removed from our Cursed Coast. Its true there’s Trouble’s at Bengal, but its good fishing in Muddy Water.’[12] His brother replied, stating he would talk to Lord Elibank and Sir Lawrence Dundas about getting an exchange but expressed his misgivings about Bengal whichhe believed ‘more unhealthy’ and ‘more dangerous than any station in all India’.[13]Even so, the Company did instigate some changes in the face of the French attack on Sumatra. The council at Madras had written to London in 1761 that ‘the Papers delivered in by Govr Carter have been examined, tis thought they put too great a Confidence in the Mallays’, continuing ‘Slaves will be much wanted at West Coast when the place is resettled’.[14] Duncan Clerk assured Hall from Scotland in 1764, ‘I find the Company are resolved to take better care of you, if another war should break out; There will soon be a considerable military force in India.’[15] Hall never succeeded in getting a transfer to Bengal and instead returned to Fort Marlborough on 11 September 1764. Nor did he benefit from the Company’s ‘reforms’ when he returned to Sumatra, dying there just over two months after his arrival.

[1] Alexander Hall to sister [Isabella Hall?], 9 December 1755, NAS, GD206/2/504.

[2] Alexander Hall to George Pigott [copy], NAS, GD206/2/502.

[3] Alexander Hall to East India Company Directors, 10 March 1762, NAS, GD206/2/502.

[4] Alexander Hall and Richard Wyatt to Christian Ludowick Senff and Frederick Van de Wall, 16 June 1760, NAS, GD206/2/502.

[5] Alexander Hall to East India Company Directors, 10 March 1762, NAS, GD206/2/502.

[6] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 17 April 1762, GD206/2/499/19.

[7] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 8 April 1762, NAS, GD206/2/499/18.

[8] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 17 April 1762, GD206/2/499/19.

[9] Alexander Hall to East India Company Directors, 10 March 1762, NAS, GD206/2/502.

[10] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 17 April 1762, GD206/2/499/19.

[11] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 2 December 1762, GD206/2499/22. See also, George K. McGilvary, Guardian of the East India Company: The Life of Laurence Sulivan (London, 2006), 80.

[12] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 3 September 1763, NAS, GD206/500/24.

[13]John Hall to Alexander Hall, 15 February 1764, NAS, GD206/2/294.

[14] Extracts from Madras Letters, 7 March 1761, NAS, GD206/2/502.

[15] Duncan Clerk to Alexander Hall, 4 January 1764, NAS, GD206/2/502.