Entering the Company Service

Hall’s position in the East India Company was secured with the aid of his eldest brother’s loyalty to the British state. In the aftermath of the Jacobite uprising of 1745, this brother (Sir John Hall, 3rd baronet) was one of the Grand Jury for the trial in 1748 of the Jacobite rising rebels at Edinburgh. Alexander wrote to him, ‘I went to Hume-Campbell to whom I propos’d my going to the East Indies he was pretty sure he cou’d find Interest to get me into the Company’s Service but he desired to write to my Mother for her Consent to my going as he didn’t care to go about it without that. Another Reason for my writing you was that I was sure you wou’d like the Scheme’.[1] Hugh Hume-Campbell, third earl of Marchmont (1708–1794) was both a great landowner in the Halls’ native Berwickshire and a staunch supporter of the Union, helping defend Berwick in 1745 and supporting the actions of the Duke of Cumberland. While empire, especially Jamaica and India, has long been seen as a place to reform Jacobites and integrate them into the British state,[2] the recognition that positions in the East India Company were given out to reward loyal Scots is less widely recognised. Indeed, while Jacobites often ended up in the Company Army, Hall was rewarded with a civil post, offering a lower likelihood of death and greater pay. The superior nature of his post was one way Hall convinced his mother to let him go to India, arguing ‘if I don’t go there I will inevitably end up in the Army’.[3] In the year before Hall departed for the subcontinent he bought various items of clothing and began to ‘learn to speak not only French but English’.[4] This learning of ‘English’ was a means for Hall to erase his Scottish accent and integrate himself into the ‘British’ East India Company, especially pertinent in the aftermath of the Jacobite rebellion.

In November 1750, Hall received word that he had been appointed a factor at Sumatra, which he informed his mother was ‘is as much as I could expect’.[5] During the period Sumatra appears to have gained a reputation for being a dead-end destination for the ambitious Civil Servant. In 1770, James Swinton wrote of his relative, ‘Tommy Swinton is gone out a writer to Bencoolen, & sailed about a Month ago in the Harcort, being all my Brothers Interest exerted to the utmost cou’d procure for him’.[6] The period between Hall’s appointment to Sumatra and his departure to the territory from Kent was only three weeks, and his letters before departure worry about his outfitting for India and pester his brothers for money to invest in the East. In the midst of this tumult, Hall wrote to his eldest brother John, ‘I never was in such a hurry in my Life. I was last night at Court in one of Willie’s Coat’s [sic]. Direct my Sheets &c., to Mr Gilbert Eliot’s care Searcher at Gravesend & mind some Table napkins. Tell the Captn who carries it to have the parcell [sic] at hand when he passes Gravesend if it be John Fergusson I am sure he’ll oblige me much’.[7] This extract suggests how preparations for India were dependent on family and friendship networks: Hall wore his brother William’s coat for his interview by the Court of Directors while responsibility for the shipping of his sheets from Scotland to Kent was given to Fergusson, a family friend. This was due to financial necessity. As Hall wrote to his mother, ‘I shall want some things that are so extravagant here I must give Tib [his sister] the trouble of providing for me I shall want 2 or 3 (at most) pairs of Sheets & one dozen of Towels let them be hem’d & mark’t’.[8] Hall’s eldest brother John covered the £170 cost of kitting him out. Nor were all of Hall’s goods for himself. The bill Alexander presented to John read, ‘Passage £40, Wine £35, “Wearing Apparel &c. and a 1000 Small things some to sell, some for my own use”’.[9] In exchange for covering his costs, Alexander promised to try to provide John with ‘Gay Pyots pink Nutmegs’, and black and white pepper from Batavia.[10] This kind of reciprocal trade suggests the role of family and friendship networks in gaining, funding, and kitting out Hall for an Indian career.

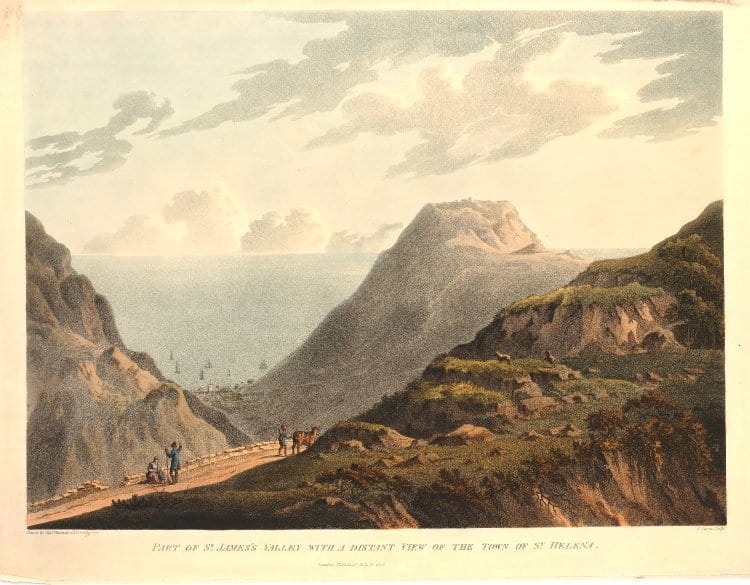

Captain Thomas Hastings, Part of St. James’s Valley with a distant view of the town of St. Helena. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Hall set sail for the subcontinent in December 1750. The first port at which the ship docked was St Helena, after 12 weeks and three days at sea. Hall reported back to his brother John, ‘Lord Northest[?] missed it & Said he was Sure there was no Such Island.’ Hall continued: ‘You can’t imagine a more barren place than this, it is wholy a grey mouldering Rock, very high & Mountaneous [sic] indeed they feed a few Cattle in the Valleys which is Reckoned next to the English Beef in all the Voyage to India’[11] Hall’s time at St Helena allowed him to gain knowledge of his station with sailors on ships from China and Bencoolen which ‘gave pretty good Accts of the Place’.[12]

Hall wrote three (surviving) letters from the island. They offer insight into how he divided his news and varied his style depending on the intended recipients. In a letter to his mother, he reassured her about his health and the climate: ‘I have kept my health very well ever Since I left England not being So much as Sea Sick & I agree mightily with their Warm Climate This Island is Reckon’d a fine Temperature in So much, that the Small pox was never known here, but if any of the Natives go to Europe they run a very good Risk of having them & that in Abundance.’[13] He offered few other details of St Helena and instead told his mother she could read his brother John’s letter for such information. He added a note for his sister Isabella, ‘Tibb knows I can have nothing to write but what I have already but anything from her wou’d be very Acceptable to me, especially about Old Reekie.’[14] In his letter to John, as well as a long description of the island, Hall also dwelt on one of his fellow recruits:

We had a very comical mortle [sic] aboard (a Brother factor) we made him believe a thousand things, we called him a Poet, he made Verses, he Sh_t his Breeches off Tenerif, he hurt his Thumb, in Saving of his Bumm (for we had a Parson aboard for this Island, who took great delight in Bumming him (with a Board) as he term’d it) we made him believe it was broke & so by way of Splicing it the Bodily Doctor clapt on a Blistering Plaister, which put me in mind of Captn Mackleish’s officer, he was a great Lyar too, we got diversion with him the whole voyage.[15]

Hall’s account offers insight into how lengthy periods on board ship could be filled. There is a childishness to his description obvious in his repeated use of ‘Bumm’, and his revelling in his fellow recruit’s incontinence and gullibility. While this somewhat crude account was acceptable reading material for Hall’s sister and mother, Hall’s letter to his brother William highlights that certain subjects were still unsuitable for female members of the family. In the letter he complained of St Helena, ‘This Island is almost entirely Rock & I dare Say almost as bad as ever you saw going into Italy, in 9/10ths inaccessible’.[16] Hall’s comparison of St Helena to Italy was in reference to the Grand Tour his brother had taken the previous year. It allowed Hall, as the youngest son, to make some assertion to himself as a cultured gentleman in the mould of his brother, albeit it a global tour in comparison to a European one.[17] Doing so, he situated imperial service within a greater classical and genteel tradition of travel — at once normalising such service and rendering it legible to his brother. Not all of Hall’s journey was as sophisticated as the classical learning offered by the Grand Tour, however.[18] To his brother William, he confided of their mutual friend Morrison, ‘I forgot if I told you of his misfortune (before I came away) in his getting a humming Clap poor man in Scotland’.[19] Hall felt comfortable sharing this information because his brother was currently on the Continent and therefore his letter was unlikely to be read by anyone other than the intended recipient. The different accounts, spread over three letters to his brothers and mother, demonstrate the epistolary tactics employed by Hall. He described St Helena and his journey variously through the lens of health and climate, childish humour, or the Grand Tour depending on the expected recipient.

[1] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 9 November 1749, National Archives of Scotland (henceforth NAS), GD206/499/1.

[2] See the case study on Downie Park for an example of a Jacobite family securing Army positions in India: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/case-studies-2/william-rattray-of-downie-park/

[3] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 9 November 1749, NAS, GD206/499/1.

[4] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 9 November 1749, NAS, GD206/499/1.

[5] Alexander Hall to Margaret Hall, [c. November 1850], NAS, GD206/4/2.

[6] James Swinton to David Anderson, 23 March 1770, BL, Add. 45429/41-42.

[7] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 15 November 1750, NAS, GD206/499/9.

[8] Alexander Hall to Margaret Hall, [c. November 1850], NAS, GD206/4/2.

[9] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 29 November 1750, NAS, GD206/2/499/11.

[10] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 13 December 1750, NAS, GD206/2/499/13.

[11] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/2/499/15.

[12] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/499/15.

[13] Alexander Hall to Margaret Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/4/2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Alexander Hall to John Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/499/15.

[16] Alexander Hall to William Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/401/2.

[17]On the Grand Tour, see Rosemary Sweet, Cities and the Grand Tour: The British in Italy, C.1690-1820 (Cambridge, 2012).

[18]Although, sex was often a feature of the Grand Tour. Ian Littlewood, Sultry Climates: Travel And Sex (Cambridge, MA, 2001), 11-54.

[19] Alexander Hall to William Hall, 26 March 1751, NAS, GD206/401/2.