Bond Family Members in the East India Company

By Angela Nutting

Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in June 2014. The case study was last checked by the project team on 19 August 2014.

For citation advice, visit ‘Using the website’.

This case study is part of the history of my late husband, Philip Nutting’s extensive family, and that of my children.When Philip’s mother died in the late 1970’s, her husband having died a few years earlier, it fell to us to clear her house. In the loft we found a large box with six pictures in it and a large bundle of old family papers. The pictures were four miniatures, a water colour, painted by George Augustus Bond (1792-1851) of a battle at sea, and a charming painting of a ship being built, supported by wooden scaffolding, on a rural shoreline.

The documents included many wills, administrations and trusts, as well as birth, marriage and death certificates, newspaper cuttings, obituaries and two papers referring to the East India Company. We also found several indentures and five apprenticeship documents, for shipwrights, which had been in the possession of the Howes Family and dated back to 1717. George Augustus and Margaret Bond’s daughter Augusta Mary married into the Howes family in 1852. There were also two locks of baby hair from the nineteenth century and a charming hand painted Valentine, posted before stick-on stamps. There were also pencil drawings of houses on St Helena with the names of families who lived there.

We had always known that George Augustus Bond had been Dock Master of the East India Docks, as we had his calling card. We had also regularly seen the collection of six prints of St Helena and a large map of the island that hung in Philip’s mother’s house, but we had not been aware of their significance. Finding this new collection of documents was fascinating and as I had spare time, I set to work unravelling the family’s history. I made many trips to London to the various record offices sometimes I would be lucky and find a printed pedigree. Today, family genealogical work seems simpler, with the wide range of digital sources, which can be easily accessed through the internet. It has been fascinating to unravel this piece of history that would otherwise have been lost to us. Completing the research and writing the current study has presented many further questions and avenues of discovery.

The beginnings of the Bond Family and its links to trade

The Bond Family lived and farmed the land around Newbury for many generations. In the early modern period, the Bond family began to grow flax to captialize on the rope and sail making industries important to the area. One family member, James Bond (1612-81), transitioned from farming to artisanal work and became a rope maker.[1] The sails and ropes were taken by barge from Newbury to a key shipbuilding site – the Thames Estuary, the River Kennet having been made navigable. Perhaps owing to James’s occupation, the Bond family became quite wealthy and James is described as a ‘Gentleman’ in a list of freeholders in 1655.[2]

Later generations of the Bond family became increasingly immersed in global networks. Resident in Tooting, James Bond’s grandson, Benjamin (1689-1763) became a Turkey merchant in London and had offices in Leadenhall Street.[3] Through this trade, Benjamin became wealthy and married Catherine Corbet in St. Paul’s Cathedral in April 1718.[4] As a Turkey merchant, Benjamin traded goods from the Levant, at the Mediterranean end of the Silk Route.[5] These goods were brought to London, and so began the Bond family’s close connection with global trade.

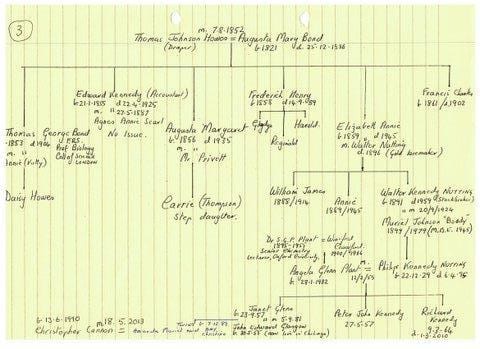

Figure 2. Bond family commemorative plaque, Merton Church, Surrey. Image courtesy of Angela Nutting.

George Bond (1727-1792)

George was the son of Benjamin and grewup in Tooting. In 1749, he married Eleanor, the daughter of Sir Thomas Chitty (1696-1762) (later Lord Mayor of London). Sir Thomas Chitty owned land at Merton in Surrey, including Merton Church, which he left to George and Eleanor.[6] Of their seven children, Essex Henry became an East India Company (EIC) captain, George a lawyer and Charles, the Vicar at Merton (as did one of their grandsons).[7] A commemorative plaque notes that George and Eleanor were buried at Merton Church along with many other Bonds (see figure 2). In 1766, four years after acquiring the land and church at Merton, George and Eleanor added further properties to their portfolio by buying Eagle House in Wimbledon. The house, a still extant Jacobean Mansion built in 1613 or 1617 by Robert Bell of the EIC, was rented out and principally acted as an investment for the family (see figure 3 below).[8]

Essex Henry Bond (1762-1819)

Essex Henry, the youngest child of George and Eleanor, married Mary Young on St Helena in 1791 and they had eight children.[9] St. Helena is an Island in the south Atlantic where ships would call to pick up fresh supplies on their long journey to Asia (in fact Essex Henry was in St Helena in 1791 as he was making a return voyage from China as captain of the Royal Admiral).[10] There was a large EIC fort there. Essex Henry first went to sea aged fourteen as Captain’s servant upon the Royal Admiral and worked his way up through the ranks serving on several EIC ships, before getting his first command in 1789, again on the Royal Admiral. He made seven journeys to Asia as a commander, each lasting about two years.[11] By studying the Principal Managing Owners (PMO) of the ships he commanded it is possible to see that Essex Henry benefitted from close links with John Pascall Larkins, who played such an influential role in Asian trade during this period by being among the first to finance the building of larger ships specifically designed for the China trade.[12] Larkins acted as PMO to four of the seven ships he commanded, a connection that also later benefited Essex Henry’s sons.[13]

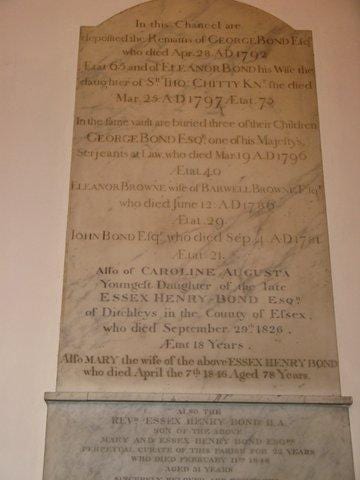

Figure 4. Miniature of China trade fleets lying at anchor off Whampoa island. Image courtesy of Angela Nutting.

In 1792 Essex Henry commanded the Royal Admiral and took one of the convict fleets out to Port Jackson in Australia, now Sydney.[14] He then went on to China to pick up goods for the return journey. A small miniature of the China trade fleets lying at anchor off Whampoa island, down river from Canton, remains in the family collection (see figure 4). Junks were used to convey the goods up and down the river to Canton. Essex Henry also commanded the Walmer Castle and the Taunton Castle. It seems that Essex Henry financially benefited from his involvement in the lucrative EIC trade and mixed socially with many high ranking people on his returns to Britain.[15] I have a record of his childrens’ god parents, amongst them, Sir Henry Baring, Lord Strathallen, Lord Hood and the then Princess of Wales.[16] The benefits that Essex Henry accrued from East India Company service are also displayed in his house – Dytchleys, near Brentwood in Essex.

Figure 5. Dytchleys (also known as Ditchleys), near Brentwood in Essex. Image courtesy of Angela Nutting.

Dytchleys is built of brick, which has been colourwashed and its seven-bay formed is topped by a concealed peg-tiled roof (see figure 5).[17] In his The Buildings of England series Nicholas Pevsner dated the building of Dytchleys to 1729 and described it as a ‘Seven-bay brick house of two-and-a-half storeys with a three-bay pediment and Tuscan porch’.[18] Pevsner and James Bettley also note that the grounds of Dytchleys were adorned with ‘a Chinoiserie tower at one end’.[19] Did Essex Henry Bond build this tower in remembrance of his East India Company voyages? Essex Henry’s will confirms that he owned and lived at the house in Essex.[20] Ownership is further confirmed by its being mentioned in the deeds of Dytchley, currently held in the Essex County Record Office.[21]

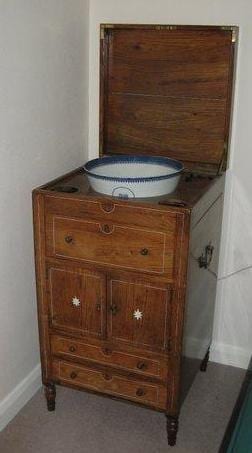

Some of Essex Henry’s possessions still exist and gesture at the rich material culture which he acquired and which accompanied him on voyages. These possessions include his small silver nutmeg grater (see figure 6), which must have gone on his voyages to disguise the smell of rancid food, and his large portable wash stand (with some of its china, inscribed with his initials – see figure 7). Two treasured paintings of his voyage in 1792, inscribed on the back by his grand daughter, are also extant. That these objects continue to be valued and treasured by his descendants suggests that they act as important reminders of the Bond family’s past connections to the global lives of Britain’s seafaring men. They also act as an important reminder within the East India Company at Home project that while Indian and British houses acted as important sites for the assemblage of material culture, EIC captains also came to acquire objects and to learn and practice furnishing while on board ship.

Figure 7. Washstand and ceramic wares belonging to Essex Henry Bond. Image courtesy of Angela Nutting.

Figure 7. Washstand and ceramic wares belonging to Essex Henry Bond. Image courtesy of Angela Nutting.

While Essex Henry remained at Dytchleys his brother, and later his son, worked as the Vicar of Merton in Surrey. Given the size of the house, it is possible that Essex Henry’s mother Eleanor, returned to live there after George died, and that Essex Henry and his family visited on high days and holidays to worship at the church. The church is small and when Nelson lived with Lady Hamilton at Merton Place in his final years he worshipped there also. The Nelson Pew is still standing. Did they all know each other? It seems possible that with shared seafaring and social backgrounds they may have done.

Of his children, George Augustus (1792-1851), his eldest followed him to sea, while his third son went to sea but then became Vicar of Merton. Two later sons became writers in the EIC and one died in India.[22]

George Augustus Bond (1792 – 1851)

George Augustus was the eldest child of Essex Henry and Mary. He married Margaret De Fountain Kennedy in 1820, again on St. Helena (while George Augustus stopped off on his return voyage from China). They had ten children and lived in Greenwich at Claremont Cottage.[23] He began his EIC career as a Midshipman in 1808 and a miniature depicts him in his uniform (see figures 8). He worked his way up through the ranks (working on nine further voyages as 6th mate, 4th mate, 3rd mate, 2nd mate twice and then four times as 1st mate) until 1832, when he became Master of the East India Dock and began to live in Poplar. A calling card shows the importance of his position and his need to retain networks and connections. He died in service in 1851. Amongst his possessions, a few remain in the family’s collection: a miniature of George and one of Margaret (see figures 8 and 9), silver flatware, a beautiful bracket clock made in Greenwich and an early ‘photograph’ printed on glass of George and Margaret with their daughter, Margaret. It depicts a very Victorian scene, complete with potted palm.

Conclusion

Angela Nutting’s case study raises many questions for The East India Company at Home project and broader histories of empire, Britain and India. Here in the lives of numerous Bond family members we can see different links to empire. Men in the Bond family became writers and captains, acquiring wealth and connections from the East India Company’s trade, which ultimately allowed them to acquire property at ‘home’ in England. How can we read this intergenerational involvement in the Company? How over so many generations were the family able to retain links with Asian trade? At the same time, the presence of such men prompts us to question the lives of female members of Bond family. In her case study Angela alludes to these women and the lives they might have lived in Britain and St Helena, but without clear occupational histories that leave archival traces less is known about them than about the family’s men.

Alongside people and houses, Angela’s case study evokes the material lives of those involved with the Company. If, as Carolyn Steedman argues, the historians craft is to ‘conjure a social system from a nutmeg grater’, Angela’s case study presses us to do just that.[24] Miniatures, wash stands, clocks and a silver nutmeg grater insist upon the transient lives lived by members of the Bond family. They also prompt many questions. What might these objects have meant to the men and women who collected them? Where and when did they acquire them? Why have these particular objects been passed down within the family? Angela’s case study offers us a glimpse into the lives of many members of the Bond family and leaves us to question the importance place, family and objects played in their lives. The study provides an important starting point to further research and ultimately further questions.

To read the case study as a PDF, click here.

Acknowledgements

The text and research for this case study was primarily authored by Angela Nutting. EICAH Research Fellow Kate Smith wrote the conclusion to the piece.

Comments

On 2 August 2014, Joan Bond Barrett left the following message:

As another descendant of this Bond family I found Angela Nutting’s report delightful, especially the images.

I, too,have done extensive research on the family including access to the records of the East India

Company.

I thought you might find of interest the brief paragraph below. It answers the question –

How could Essex Henry have had access to the Princess of Wales to ask her to be godmother to his daughter?!

The Joseph Bond to whom I refer was my ancestral link. Would you please pass this information on to Angela?

Joan Bond Barrett

Caroline Augusta Bond (b. 1808-1826) died on Sept.29 at the age of 18 at Ditchleys. She lies buried in the Bond vault at St. Mary’s Church in Merton. Her godmother was Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales. While this seems unlikely, it was indeed true. The princess would have been 12 years old when this baby was born. Her former governess was Lady Elgin, widow of Charles Bruce, 5th Earl of Elgin, who had close ties to the Bond family. She was the aunt of Eliza Finch Mills, who was the wife of Joseph Bond, Captain Essex Henry’s first cousin. The young princess was likely excited and wanted to see the new baby, and it was arranged that she could be her godmother.

[1] See ‘The Bonds of Newbury and London’ website. <http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/peter.entwistle/>

[2] See ‘The Bonds of Newbury and London’ website. <http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/peter.entwistle/>

[3] J. G. Parker, The Directors of the East India Company, 1754-90 (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1977), p. 260. Many thanks to Kate Smith for this source.

[4] Guildhall Library, Marriage Register, Ms 25, 740.

[5] For more on this trade, which intersected with East India Company commerce see James Mather, Pashas: Traders and Travellers in the Islamic World (London: Yale University Press, 2009).

[6]The National Archives, ‘Will of Sir Thomas Chitty, One of the Alderman of the City of London of Saint Lawrence’ 22 December 1762, PROB 11 882. Many thanks to Kate Smith for this source.

[7] For more on George see J. M. Rigg, ‘Bond, George (1750–1796)’, rev. Robert Brown, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/2823, accessed 26 March 2014]

[8] See ‘Eagle House, Wimbledon Village: Wimbledon Ramblings’, <http://wimbledonramblings.weebly.com/eagle-house-wimbledon-village.html>

[9] Births, marriages and deaths recorded in volume in family collection.

[10] See Anthony Farrington, Catalogue of East India Company ships’ journals and logs, 1600-1834 (London: British Library, 1999). Thanks to Kate Smith for this addition.

[11] British Library, India Office Collections, L/MAR/B338E-G.

[12] Jean Sutton, The East India Company’s Maritime Service: Masters of the Eastern Seas (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2010), p. 190.

[13] For more on John Pascall Larkins see Sutton, The East India Company’s Maritime Service, pp. 188-206. Larkins later acted as PMO on ships which Essex Henry’s sons Essex Henry Jnr and George Augustus Bond worked on. See Farrington, Catalogue of East India Company ships’ journals and logs, 1600-1834. Many thanks to Kate Smith for this addition.

[14] British Library, India Office Collections, L/MAR/B338F.

[15] Essex Henry’s will notes that he not only owned Dytchleys but also other accroutrements of gentility. The will remains in a family collection.

[16] Noted in volume in family collection.

[18] James Bettley and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Essex (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 273.

[19] Bettley and Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Essex, p. 273.

[20] His will is contained in a family collection. For more on Essex houses with East India Company connections see the Valentines Case Study and the Englefield Case Study.

[21] Essex County Record Office, ‘Deeds of mansion house called Dytchleys and land (12a), South Weald’, D/DU 667/8.

[22] British Library, East India Company Applications for Writer-ships, 1749-1856.

[23] The deeds for Dytchley, held in the Essex Record Office suggest that Mary Bond (listed as widow – presumably George Augustus’s mother) also lived in Greenwich. Many thanks to Georgina Green for looking at this source.

[24] Carolyn Steedman, ‘Something She Called a Fever: Michelet, Derrida, and Dust’, The American Historical Review, 106:4 (2001), p. 1165.