The Dundas Property Portfolio: ‘Conquests from North to South’

The Dundas Property Portfolio: ‘Conquests from North to South’

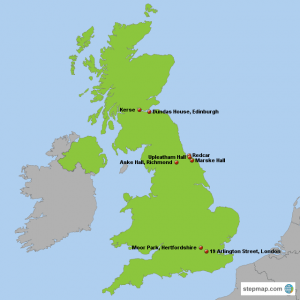

After receiving his baronetcy in 1762 (and the death of his father the same year) Lawrence Dundas began a ten year campaign of purchasing and transforming a series of magnificent houses to reflect his wealth, taste and power. He only built one major new property, Dundas House in Edinburgh, although he commissioned plans for several ambitous extensions to some of his other properties, none of which were carried through. In 1762 the Seven Years War was about to end, and Lawrence Dundas’s profits as contractor must have encouraged him to invest some of his money in landed property.

Detail of view of Moor Park by Richard Wilson. Oil on canvas, 147.3×182.8cm. Collection Marquess of Zetland.

First he acquired a cluster of modest houses on the North East coast of England at Redcar, Marske Hall and Upleatham Hall in 1762. Marske Hall had been built for Sir William Pennyman in 1625; Upleatham Hall, was described in Bulmer’s Directory of 1890 as ‘a handsome modern Mansion’ (demolished 1892).[i] To these was added, in 1764, an estate at Loftus a little further down the coast. It is unclear why he invested in these properties. Perhaps their links to the prosperous local alum trade may have been an incentive? Alum was an important mordant for setting dyes in the cloth industry, one that Dundas would have been fully aware of as the son of a prosperous draper.

Arlington Street looking north, by J.C. Buckler, watercolour, 1831. City of Westminster Public Library. Number 19 is the pedimented entrance on the left.

In 1763 he upped his stakes and entered into a phase of spectacular house purchasing. He bought Aske Hall in North Yorkshire for £45,000. On 3 May 1763 Lord Hardwicke wrote to Lord Royston ‘Sir Lory Dundas, who extends his conquests from North to South, has purchased Moor Park [Hertfordshire] for £25,000. He has contracted in his own great way; takes everything as it stands.’[ii] A few months later he bought Lord Granville’s London house 19 Arlington Street in St James’s, London for £15,000 .

A third phase began in 1772 when he commenced building Dundas Mansion in Edinburgh, completed two years later. By the time Sir Lawrence died in 1781 he owned eight major properties.[iii] Each of them conveyed messages of power, wealth and taste.

Aske Hall, North Yorkshire was a strategic purchase, bought to secure a seat in Parliament as it came with the pocket borough of Richmond, and a suitable focus for a new dynasty. Dundas’s son Thomas became MP for Richmond between 1763 and 1768. Aske Hall cost Lawrence Dundas £45,000. This can be compared with John Spencer’s construction and decoration of Spencer House in 1755 which cost £35,000, with a further £14,000 for the site and objet d’art. It was considered as one of the most splendid examples of conspicuous consumption in London of the time.[iv]

After Dundas purchased Aske Hall from Lord Holderness he proceeded to enlarge and remodel it in the Palladian taste, employing the fashionable York architect John Carr. Dundas kept the two Gothic follies probably built for the previous occupant, Sir Conyers D’Arcy, and described in Robinson’s Guide to Richmond, (1833) as a ’Temple, a tall building which towers above the woods behind the hall … built on the exact model of a Hindoo Temple; and on Pinmore Hill (between Aske and Richmond) is a Tower, bearing the grotesque name of Olliver Ducat, which is said to be a perfect counterpart of a Hindoo Hill-Fort’. The architectural historian John Harris has suggested that the Temple might be later, perhaps the work of Capability Brown, who Dundas employed to landscape his estate.[v] One wonders if they in some way reminded Dundas of one of the major sources of his massive fortune? The origin of this attribution however remains unknown.

Dundas was anxious to carry out extensive alterations as soon as possible and Carr was at Aske in November 1762, before the purchase was complete and plans were well advanced by March the following year. Work was concentrated on creating a suite of family rooms, together with offices, leaving thoughts of improving the state rooms for later. In 1767 Carr produced plans for a massive extension on the front of the house which would have turned Aske into a great classical mansion. The intended new work would have included a hexastyle portico, an apsed hall 60ft wide by 27ft wide, dining room, drawing room and a gallery 80ft by 27ft. Nothing however came of the grand scheme. Dundas was less interested in new building than refurbishing.[vi] Together with the properties in County Cleveland, north of Aske, at Markse, Upleatham and Redcar Dundas held a major interest in property in northern England. Nearly midway between London and Edinburgh Aske was perhaps a useful half-way house between the two sites of his ambition.

Moor Park was nothing if not prestigious: it was a country house connected with exceptionally powerful men. In 1670 a mansion was built by James, Duke of Monmouth, the illegitmate son of Charles II, who married him off to Anne Scott the heiress to the Earl of Buccleuch’s vast fortune. In 1732 1720 Monmouth’s widow (the Duchess of Monmouth who was also the Duchess of Buccleuch) sold Moor Park to Benjamin Haskins Styles, who had amassed a fortune from the fraudulent South Sea Investment Company. As Joanna Swan has noted, Styles transformed it into a mansion of the Palladian style. Sir James Thornhill supplied the plans. Styles died in 1738, and his nephew in turn sold it to Admiral Lord Anson (1697-1762) who had overseen the Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War, which had provided Dundas with such frutiful business opportunities. In the park Sir Lawrence employed Adam to build a Tea Pavilion, complete with a painted Palm Room. [vii]

Dundas also needed a London base. He had previously rented houses, like Hill Street, Berkeley Square in Mayfair. In 1763 he bought 19 Arlington Street, St James’s, in one of the most exclusive residential enclaves in London. It had been built in the 1730s for Lord Carteret. It was his third house purchase that year, and cost £15,000 the ‘crowning fulfilment of his political and social ambitions’.[viii]

Meanwhile in Edinburgh Dundas’s popularity had waned, and he was criticized for neglecting the city’s affairs, and for his non-residence, which he rectified by building a mansion in St. Andrew’s Square. In 1772, in a characteristically deft move Dundas outwitted the city fathers of Edinburgh and purchased a prime site in the city, which had originally been intended for a church. He employed Sir William Chambers the royal architect, fellow Scot and erstwhile employee of the Swedish East India Company, to build a fine Palladian villa as his private mansion.[ix] It was modelled on Marble Hill, in Twickenham which had been built between 1724-9 for Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk and mistress of George II.

Dundas was particpating in the country house ‘boom’ of the 1760s. As Charles Saumarez Smith has explained: ‘The immense success of Britain at war, the expansion and consolidation of her overseas empire, the profits of trade, andthe improvements which had been made in agriculture, had created a social elite … which was self-confident, assured … and wanting to be artistically commorated at home’.[x]

[i] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/NRY/Upleatham/Upleatham90.html

[ii] History of Parliament online, volume 1754-1790, Alex. Forrester to Andrew Mitchell, 12 Sept. 1763, Add. 30999, ff. 16-17.

[iii] There were others, about which to date, little evidence seems to survive within the family papers, most notably a house in Newmarket, built between 1769-71 NYCRO ZNK X/1/15/1-12.

[iv] Liza PIcard, Dr Johnson’s London, Phoenix Press, 2001, p.277.

[v] N. Pevsner, Buildings of England, The North Riding, Penguin, 1966, p.65, ‘Mr Harris is inclined to assign the Temple to Capability Brown, who is known to have worked at Aske too’.

[vi] Brian Wragg, The Life and Works of John Carr of York, York: Oblong, 2000.

[vii] Apollo, September 1967 p.176. With many thanks to Joanna Swan, a guide at Moor Park Mansion who has been researchng its history over the last 25 years, for supplying corrections to the first public draft of this case study. [Corrections to this paragraph and notes from Joanna Swan were added 18.04.13.]

[viii] Caddy Wilmot-Sitwell, The Inventory of 19 Arlington Street, 12 May 1768’, Furniture History, vol.XLV, (2009), p.73.

[ix] Chambers is credited as creating one of the earliest architectural drawings by any European of an Indian building, see John Harris & Michael Snodin, Sir William Chambers Architect to George III, Yale University Press, 1997, p. 11 ‘Plan ofthe Nataraja Temple at Chidambaram, 1748, drawn en route to Canton.

[x] Charles Saumarez Smith, Eighteenth-Century Decoration Design and the Domestic Interior in England, Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1993, p.221.