India Goods & The Importance of Kerse

India Goods & The Importance of Kerse

Yet where in this story of interior decoration are the exotic Asian goods that exist at Aske Hall today? None are mentioned in the connoisseurial articles published in Apollo. The paucity of inventory evidence surviving for the eighteenth-century relating to the Dundas properties, makes tracking their appearance and movement difficult. In the recently re-discovered 1768 inventory of Arlington Street the most exotic chattels listed are a ‘stand for a Parroquet’,‘Two Parroquets in a Cage’; and ‘Cloathes Chest of Pigeons wood in a frame’ in the Blue Bed Chamber. This exotic timber came from South America. Perhaps they may have entered the Dundas households in later centuries? Much of the career of Laurence John Lumley Dundas, 2nd Marquess of Zetland (1876 -1961) was centred on India. In 1912 he was appointed a member of the Royal Commission on the Public Services in India of 1912–1915, was Governor of Bengal between 1917 and 1922 and Secretary of State for India between 1937 and 1940.

At Moor Park, the only evidence in the inventory of Asian goods is in the list of chinaware, which included ‘Mr Anson’s India set of tea china finely painted with landscapes’.[i] According to Lord Hardwicke, Dundas took ‘everything as it stands’ at Moor Park when he purchased it on Anson’s death in 1762. A porcelain soup plate from a complementary dinner set in the British Museum, reveals that it may have been manufactured at Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, China c. 1743-47.[ii] What is left of the 208-piece armorial service can be seen at the Mansion House in Shugborough. It was acquired during George Anson’s months in Canton in 1743, which are recorded in his Voyage Round the World (1748). Stephen McDowall in his East India Company at Home case study of Shugborough, another of the Anson homes, examines in more detail the relationship of the Anson brothers, George and his older brother Thomas, with the Chinese and Chinese-style objects that were associated with the Chinese House erected on the Shugborough estate in 1747. Clearly Lawence Dundas and his family would have had very different attitudes towards this very personal tea service, but found it sufficiently appropriate for their own use, ‘second-hand’.

It comes as a surprise then, to find an unusual concentration of ‘India goods’ in a rather overlooked Dundas property, Kerse in Stirling, purchased by Lawrence Dundas, c.1749. As John Harris has noted, although it was ‘an unremarkable five-bay three-storey house’ with little architectural merit, it was a very significant purchase for Dundas In spite of Sir Lawrence’s ancient Scottish lineage, he and his immediate forbears maintained no Scottish house of consequence before the acquisition of Kerse (It was demolished in 1958.) When Sir Lawrence was created a Baronet in 1762 it was as Baronet of Kerse in the County of Linlithgow. It was also a commercially astute purchase, being near Grangemouth which Sir Lawrence founded in 1768, during the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal, which passed through the Kerse esate. Grangemouth was to become a bustling and successful port (today it is the largest container terminal in Scotland).

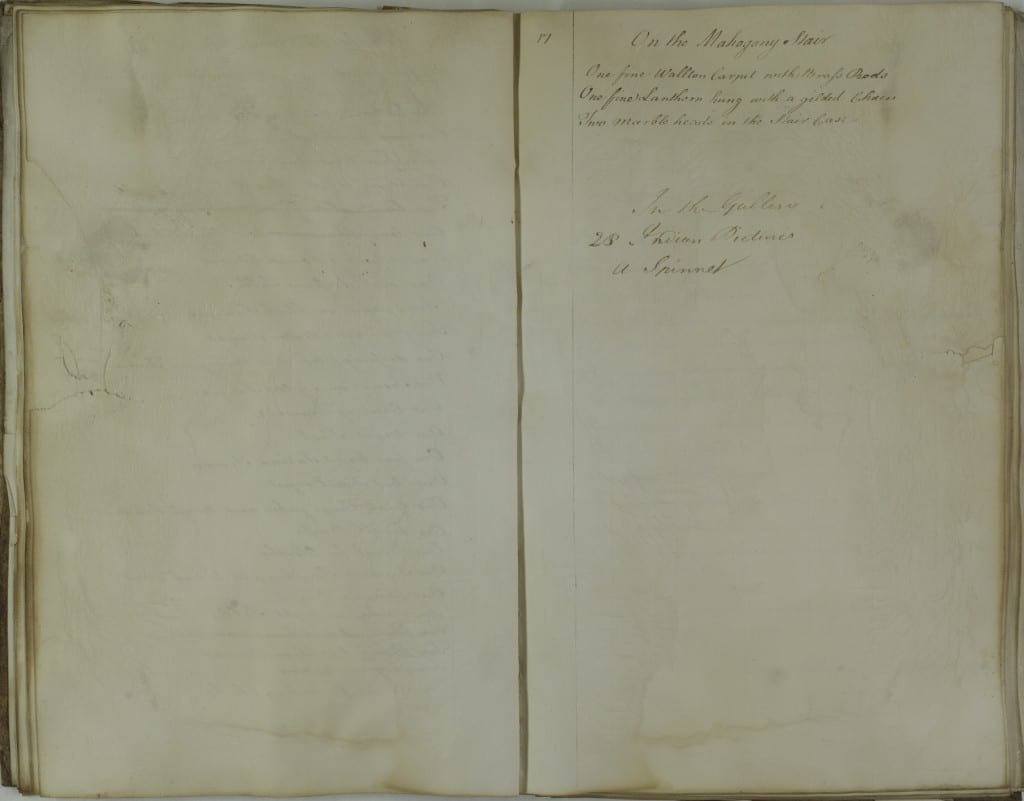

All this seems a long way from any exotic connections. However, the discovery of an inventory dated 1763 of Kerse, in a green bound and rather water-damaged cover reveals a wealth of ‘India goods’.[iii] [Images 22–23 pages from the 1763 Inventory, NYCRO ZNK XI] In the Gallery were ‘28 Indian Pictures’;[iv] in the Drawing Room ‘one settee with blew Indian Sattin Work’d’ with two elbow and eight plain chairs upholstered to match, ‘Two Indian Cabinets’ and ‘an Indian Trunk’ with ‘Two fire Screens with Indian paper’. Lady Dundas’s bed and dressing rooms contained a mixture of what appeared genuinely Asian goods with fashionable western imitations. In her bedroom she had a glass with a ‘Chinese frame’, probably carved in Britain, perhaps from Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director: being a large collection of the most elegant and useful designs of household furniture in the Gothic, Chinese and modern taste (1754). Her dressing room contained an ‘Indian trunk’and an ‘Indian dressing box with a pin cushion in the top’. Her dressing glass was set within a ‘japann’d frame’ (in imitaiton of Chinese lacquer). It is not clear what type of ceramics she had in the ‘China press’ which sat upon a mahogany chest of drawers. The ‘Blue Guise Room’ housed a ‘four leafed Indian screen’ with ‘blew and white China water pots’ and basins. A ‘four posted Mahogany Bed stedd with Indian worked Sattin Furniture and counterpaine of the same’, stood in the Blew Silk Room, the adjacent dressing room contained a‘dressing Glass with a Japan’d frame’, with ‘Six Chinese Chairs with Cushion cover’d with blew and white cotton’. These too are likely to have been derived from Chippendale’s Director.

This concentration of East India Company goods is magnified when one takes into account the relatively small scale of Kerse compared to Dundas’s other properties. For example there are thirty rooms listed in the Kerse inventory. Aske by comparison accommodated 38 bedrooms alone.[v]

These goods clearly had a very specific meaning to the Dundas family, quite separate from the show and status of the more recently acquired Aske, Moor Park and Arlington Street homes, which contained none of these Asian sourced goods, or even European imitations of them. An inventory of the library at Aske in 1839 hints at more than a passing family interest in Asian affairs.[vi] It includes Jean-Baptiste Du Halde’s two volume History of China, published in 1736; the Scottish sea-captain, privateer and merchant Alexander Hamilton’s Account of the East Indies (1727), and Bartholomew Plaisted’s Journal from Calcutta (1750).

Kerse was the ‘family’home, furthest north, deep in the dynastic hinterland of the Dundas clan. It was regularly occuppied by Sir Lawrence and his family, as letters which are dated and signed with the place of writing prove. Sir Lawrence died in London, but chose to be buried near Kerse, in the family mausoleum in Falkirk Church. These exotic goods, which were created so far away, shipped across oceans, turn out to have been part of the modest, private, familial core of one of the most wealthy men of his day.

[i] NYCRO ZNK/X/!/ 0050 Inventory of plate, china and linen at Arlington Street, Moor Park and Aske Hall, 1781. Taken on the death of Sir Lawrence Dundas.

[ii] British Museum Asia OA 1892, 6-16, 1, decorated with the coat of arms of Commodore, later Admiral, Lord Anson (1697–1762) and two panels containing a view of the Pearl River (right) and Plymouth Sound in Devon (left). George Anson was in Canton (Guangzhou) in 1743.

[iii] NYCRO ZNK, X/1/0002, Inventory of Kerse House, November 1763.

[iv] These are not mentioned in Denys Sutton’s article, ‘The Dundas Pictures’, Apollo, September 1967, pp.204-213.

[v] NYCRO ZNK /XI/0121 Inventory of the household furniture, glass, china and linen at Aske’, 22 March 1839. Taken on the death of Thomas Dundas, 1st Earl of Zetland, grandson of Lawrence Dundas.

[vi] NYCRO ZNK /XI/0121, as above.