Jeremy Bentham, revision, and self-censorship: the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’

By Tim Causer, on 10 October 2018

To say that Jeremy Bentham was a prolific writer would be a massive understatement: UCL Library Special Collections and the British Library hold between them some 100,000 manuscript pages which he either wrote or composed. According to Bentham’s literary executor John Bowring—who oversaw the production of the eleven-volume edition of Bentham’s works and correspondence published from 1838 to 1843—Bentham wrote, ‘on an average, from ten to fifteen folio pages a-day. He was seldom satisfied with the first expression of his thoughts, and generally developed his views over and over again’. Bentham would also have written many more than the 100,000 or so extant pages, as when he printed or published a text he typically destroyed the manuscripts on which it was based, making it impossible to trace the iterative development of a text in the manner described by Bowring. (For more on Bentham’s writing process, see P. Schofield, Bentham: A Guide for the Perplexed, London, 2009, pp. 30-5).

‘Jeremy Bentham writing, 1827’, engraving by George Washington Appleton after Robert Matthew Sully, ‘The Yankee: and Boston Literary Gazette’, vol. i (1829).

Editing Bentham’s ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’ (1802-3), which exists only in manuscript and has recently been made available for the first time for a volume of his Writings on Australia, provides a brief glimpse at certain stages of Bentham’s writing process. In two preceding ‘Letters to Lord Pelham’ (Pelham then being the Home Secretary) Bentham had condemned both the practice of transporting convicts to New South Wales and the government’s preference for transportation over his panopticon penitentiary scheme, which he had spent much of the last decade trying to persuade the British government to adopt. In the ‘Third Letter’ Bentham turned his attention to the other two major forms of punishment which the government also appeared to prefer over the panopticon, namely what he referred to sarcastically as the ‘improved prisons’ of England and Wales, and the prison hulks, dismasted ships moored on the Thames, at Plymouth, and at Portsmouth.

Surviving among UCL’s Bentham Papers are two (perhaps two and-a-bit) versions of the ‘Third Letter: first is a manuscript draft, dating from November and December 1802, in Bentham’s hand and featuring heavy revisions on several pages; second is a revised fair copy, based on the draft and presumably dating from early 1803, in the hand of Bentham’s amanuensis John Herbert Koe, though with corrections and emendations in Bentham’s hand; finally, the ‘bit’ is a printed sample proof of the first six pages of the prospective text which Bentham had presumably sent to the printer in 1803, before he ultimately decided to abandon the ‘Third Letter’.

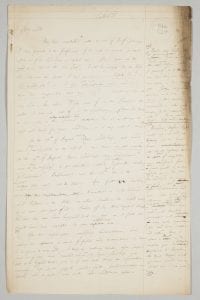

First page of the ms draft of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’, in Bentham’s hand.

(UCL Bentham Papers, Box 116, fo. 534

First page of revised fair copy of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’, in Koe’s hand with corrections by Bentham.

(UCL Bentham Papers, Box 117, fo. 254)

First page of the sample printed proof of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’, with corrections by Bentham.

(UCL Bentham Papers, Box 117, f. 261)

In late 1802 and early 1803 Bentham had privately printed the first two ‘Letters to Lord Pelham’ and a connected work, ‘A Plea for the Constitution‘, in the hope that the arguments they contained would cajole the government into proceeding with the panopticon. In addition he threatened on several occasions to publish the texts and go public with his allegations about the various illegalities of New South Wales and the corruption of the ministers who had sanctioned them, but each time he held back from following through on those threats. The suspicion is that Bentham realised that to publish these quite radical and subversive texts, so critical of the government and its ministers at a time of fear of political radicalism, could have been calamitous for his reputation and perhaps even for his liberty. (For instance, in February 1803 war with France loomed, and Colonel Edward Despard had been convicted of leading a conspiracy to overthrow the government and assassinate George III). Bentham expressed a particular fear that if his argument, made in ‘A Plea for the Constitution’, that New South Wales had been illegally founded and that the governors’ various local ordinances were all illegally issued, it could prompt a convict uprising and see the ‘setting of the whole Colony in a flame’. Bentham may have feared prosecution for not only seditious libel, but plain libel as well. In this sense, Bentham’s revision of certain parts of the ‘Third Letter’ might have seen Bentham engage not only in self-censorship, but also self-preservation.

Thanks to the wonderful Juxta Commons, a tool produced by Networked Infrastructure for Nineteenth Century Electronic Scholarship (NINES) which allows for the comparison and collation of versions of the same text, it is possible to more closely examine the differences between the draft and the revised fair copy of Bentham’s ‘Third Letter’ (which we have made accessible through the Juxta Commons interface—please see the links below). Juxta Commons’s side-by-side visualization feature displays the draft and the revised fair copy alongside one another, and highlights where the differences between them are found. The majority of these differences consist of relatively slight changes to words and phrasing, correction of spelling, punctuation, and other alterations for sake of clarity—or, in other words, the typical finessing of a text which any writer goes through when drafting and redrafting a work.

There are, however, a number of significant differences between the draft and the revised fair copy, with Bentham presumably having decided that it would be wiser not to include in the latter several rather incendiary passages which he drafted for the former, which touch upon what in Bentham’s view was the deliberate cruelty and corruption of the ministry. The revised fair copy was sharp enough in Bentham’s personal criticism of Pelham and his immediate predecessor as Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, for having overseen the conditions leading to the appalling mortality aboard the Portsmouth hulks; in the draft Bentham’s criticisms on this point were if anything more vicious.

For instance, Bentham drew comparison between the mortality on the hulks of Langstone Harbour, where in 1801 120 of 500 convicts had died, with the infamous ‘Black Hole’ of Kolkata, a small prison in which, according to the East India Company employee John Zephaniah Holwell, 143 of the 164 British prisoners-of-war died when confined there on the night of 20 June 1765. Invoking the rhetorical power of the ‘Black Hole’, Bentham claimed that conditions on the hulks were in fact far worse and were the result of Home Office policy. As Bentham put it, the ‘Black Hole’ would ‘henceforward yield in proverbiality to Lord Pelham’s and Mr King’s and Mr Baldwin’s Hulk: the Hulk La Fortunée: for such, by a horrible catachresis, happens to to be the denomination of this ever memorable scene of official barbarity and negligence’. (Mr King was John King, Under Secretary at the Home Office 1791-1806, and Mr Baldwin was William Baldwin MP, counsel for criminal and colonial business at the Home Office 1796-1813.)

An extract from the draft (left) and the revised fair copy (right) of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’ in Juxta Commons, showing the passage comparing the hulks to the ‘Black Hole’ of Calcutta

The draft also contains Bentham’s blunt allegation of corruption and cronyism at the Home Office which was removed from the revised fair copy of the text. Bentham complained about the circumstances of the appointment, provided for by the Hulks Act of 1802, of Aaron Graham, a stipendiary magistrate at Bow Street, as Inspector of the Hulks on a salary of £350 per year. As a London police magistrate Graham’s salary had already been £400 per year, but had recently been increased to £500 per year by the Metropolitan Police Magistrates Act of 1802. Worse still for Bentham than this unwarranted augmentation of Graham’s salary was that Graham had not been appointed on merit but because he was a friend of John King, the Under Secretary at the Home Office, and because he would be willing to whitewash what had been happening on the hulks. Bentham suggested that conditions on the hulks had been allowed to become so bad until there came:

the occasion for recommending a friend [of King’s] to look at it. … A gentleman whose whole time had already been bought for the public and twice overpaid for it: paid by one Act, overpaid by another Act—an Act made on purpose. Two Acts made for one gentleman: both of them at the instance of Your Lordship’s Secretary—both of them under Your Lordship’s auspices. One to overpay a man for business he was already paid for … another to call him off from that to other business, pay and overpay still continued: one for making him receive more money: another for making him do less service.

Though this overt allegation of corruption was excised from the revised fair copy, it must be said that Bentham still hinted darkly at the circumstances around Graham’s appointment, but the point is made in a more subtle manner.

* * *

To compare for yourself transcripts of the draft and the revised fair copy of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham’, please visit the links below. As it can take some time for Juxta Commons to load the visualization for longer texts we have separated the text into the four sections in which Bentham presented it, namely:

- Section 1: a short introduction

- Section 2: ‘XV. Hulk System compared with Penitentiary and New South Wales systems’

- Section 3. ‘XVI. Penitentiary system in England—improved local prisons

- Section 4: ‘II. Hulk mortality—Sinecure made to screen it’

Please note that the third section of the text is the longest and it may take a little longer for the visualization to load than the others. The comparison has been set to ignore differences in punctuation and capitalization. Many, many thanks are due to NINES for producing Juxta Commons and for making it freely available.

Readers can also download for free a pre-publication version of the ‘Third Letter to Lord Pelham‘, which is based on the revised fair copy of the text, though collating it where appropriate with the few printed pages and the draft. The other texts constituting Bentham’s Writings on Australia can also be downloaded for free from UCL Discovery.

Close

Close