This blog is based on findings published in Journal of Research in Science Teaching.

Throughout primary and secondary school, Preeti, a British South Asian young woman, consistently named chemistry as her favourite subject. She took the subject at A level, experienced good quality teaching and obtained top grades. She had positive attitudes to the subject and recognised its value – yet Preeti never considered pursuing chemistry at degree level – why not?

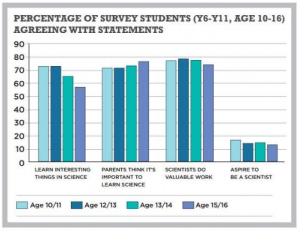

In recent years chemistry degree enrolments have been declining in England, despite increases in A Level chemistry enrolment. Researchers from the ASPIRES 3 study analysed interviews and survey responses from over 520 young people who took A Level chemistry and either did, or did not, go on to study chemistry in higher education. The findings revealed how chemistry degree subject choices were highly relational – shaped not only by young people’s attitudes towards and experiences of chemistry, but also how it related to other options.

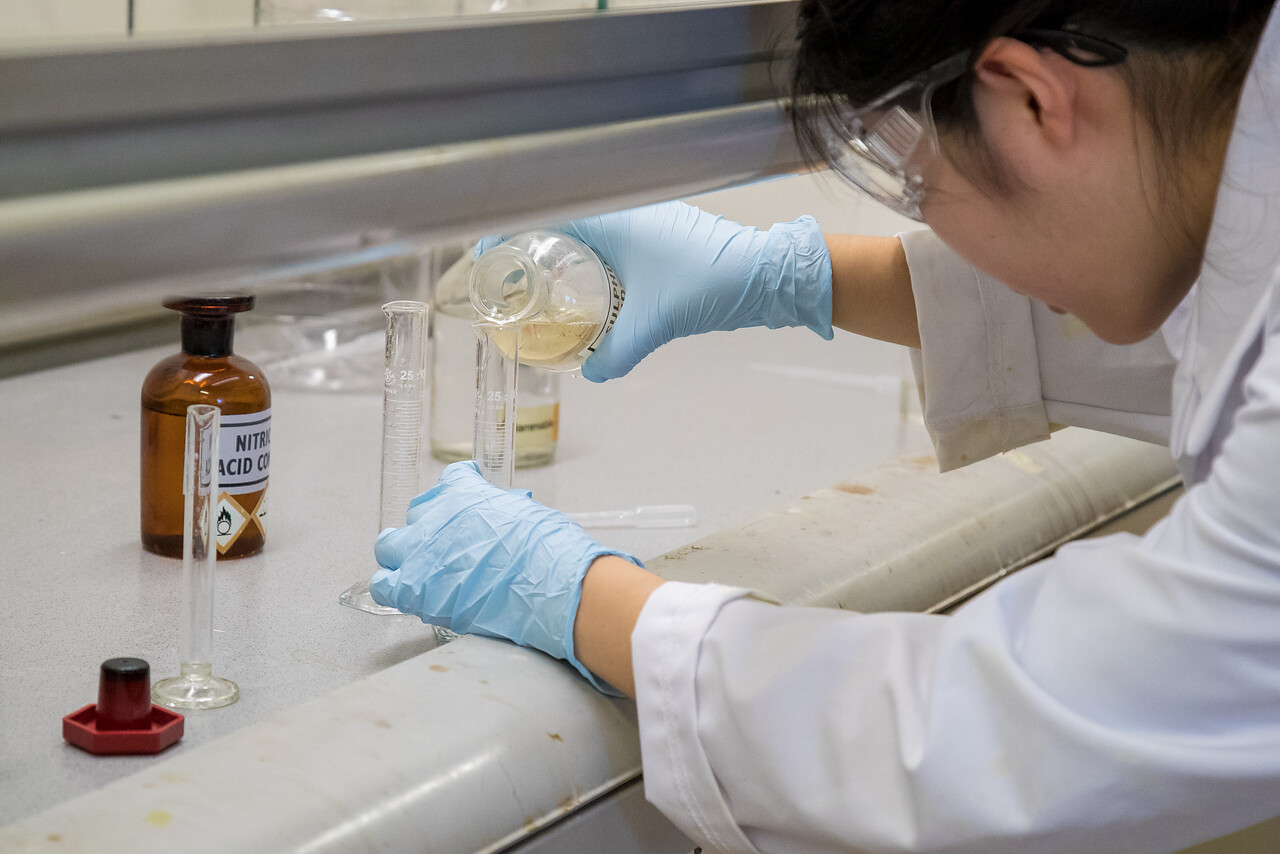

Young person during a practical chemistry lesson.

The latest round of ASPIRES data was collected when our cohort was aged 20-22. In order to understand the factors shaping young people’s chemistry degree choices, researchers analysed open-ended survey responses from 506 young people aged 21-22 and 185 longitudinal interviews conducted with 18 young people (and their parents) who were tracked from age 10-22, all of whom had taken A level chemistry.

Of the 524 chemistry A Level students in the sample, just 83 (or 16%) went on to study for degrees in chemistry or chemistry-related degrees.

One key finding was that degree subject choices are highly relational – that is, choosing a chemistry degree, or not, was not only based on young people’s views or experiences of chemistry but was formulated in relation to other options. This relational interpretation helped explain why even students with positive views and experiences of chemistry did not choose the subject at degree level.

A number of factors were identified as influencing young people’s degree choices including their experiences of school chemistry, feeling ‘(not) clever enough’ to continue with the subject, perceptions of chemistry jobs, associations of chemistry with masculinity, encouragement from others and experiences of chemistry outreach. Across all of these factors, social inequalities within and beyond chemistry affected the extent to which young people felt that a chemistry degree might be ‘for me’, producing unequal patterns of participation. For instance, common associations of chemistry with masculinity and cleverness put some young people off from continuing with the subject. This was particularly apparent for young women, irrespective of their actual attainment.

The women who did pursue chemistry spoke about having to find ways to negotiate their own femininity in the masculine world of chemistry. Some young people also described how, despite enjoying chemistry, they had found a deeper, more meaningful connection with another subject, particularly where they had related resources (capital).

Professor Archer explained, “young people’s subject choice is a relational phenomenon. Their views on chemistry do not exist in silo but are shaped in relation to other options”.

The paper makes several suggestions to better support chemistry degree uptake. Some of these suggestions include supporting teachers and initiatives to help young people find and experience personal connections with chemistry and to build chemistry-related capital by offering encouragement, information on career routes, and access to high quality chemistry work experience and outreach.

The full paper can be accessed online.

Further reading

Archer, L., Francis, B., Moote, J., Watson, E., Henderson, M., Holmegaard, H., & MacLeod, E. (2022). Reasons for not/choosing chemistry: Why advanced level chemistry students in England do/not pursue chemistry undergraduate degrees. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 1– 36. doi: 10.1002/tea.21822

Close

Close

Background

Background